Russian artists are not the enemy

The cultural boycott of Russia has taken an ugly, McCarthyist turn.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Wartime frenzy and the arts world really do not mix. That’s become abundantly clear in recent days, as the understandable desire on the part of Western cultural institutions to show solidarity with Ukraine, and express their disgust with Vladimir Putin, has morphed into knee-jerk censorship, hysteria and flat-out Russophobia. As Russian forces rolled into Ukraine, a cultural boycott of Russia emerged almost immediately, informally – before anyone could get around to campaigning for or organising one. Russia has now been cut off from swathes of Western cultural output, while Russian artists working in the West have found themselves sacked and ostracised.

Almost every sphere of culture has been caught up in this. The examples range from the shocking to the absurd. Hollywood movie studios have pulled out of the Russian cinema market entirely. Western artists have suspended exhibitions of their work in Russia. ITV has pulled I’m a Celebrity… from the Russian airwaves. EA Sports is busy expunging Russian teams from its FIFA videogames. And Russian artists and organisations have had contracts terminated and performances cancelled across Western countries.

These cultural boycotts are at once self-flattering, discriminatory and completely counter-productive. Last week, Disney pulled all its theatrical releases from Russia, swiftly followed by Warner Bros and Sony. The new Pixar flick, Turning Red, was among the first releases to be affected. On the one hand, the idea that stopping Russian children from watching a film about a teenage girl who turns into a giant red panda when she’s stressed could shift the dial in Ukraine’s favour is ridiculous. On the other, it treats even the most innocent of Russian citizens as tainted by the actions of their government, burnishing the Kremlin line that the West simply hates Russia and its people.

I understand why pop stars are cancelling tour dates in Russia, and why outspoken artists are wary of performing in a country that is taking an increasingly totalitarian turn – its government scrambling to keep the truth about its brutal war from its people. With Western citizens and journalists fleeing the country, for fear of state reprisals or being trapped within its borders, even getting into Russia will be incredibly difficult – not to mention unwise – for some time to come. But the idea that Russian audiences should, on principle, be sealed off from Western culture for the foreseeable future risks ushering in an unpleasant new era.

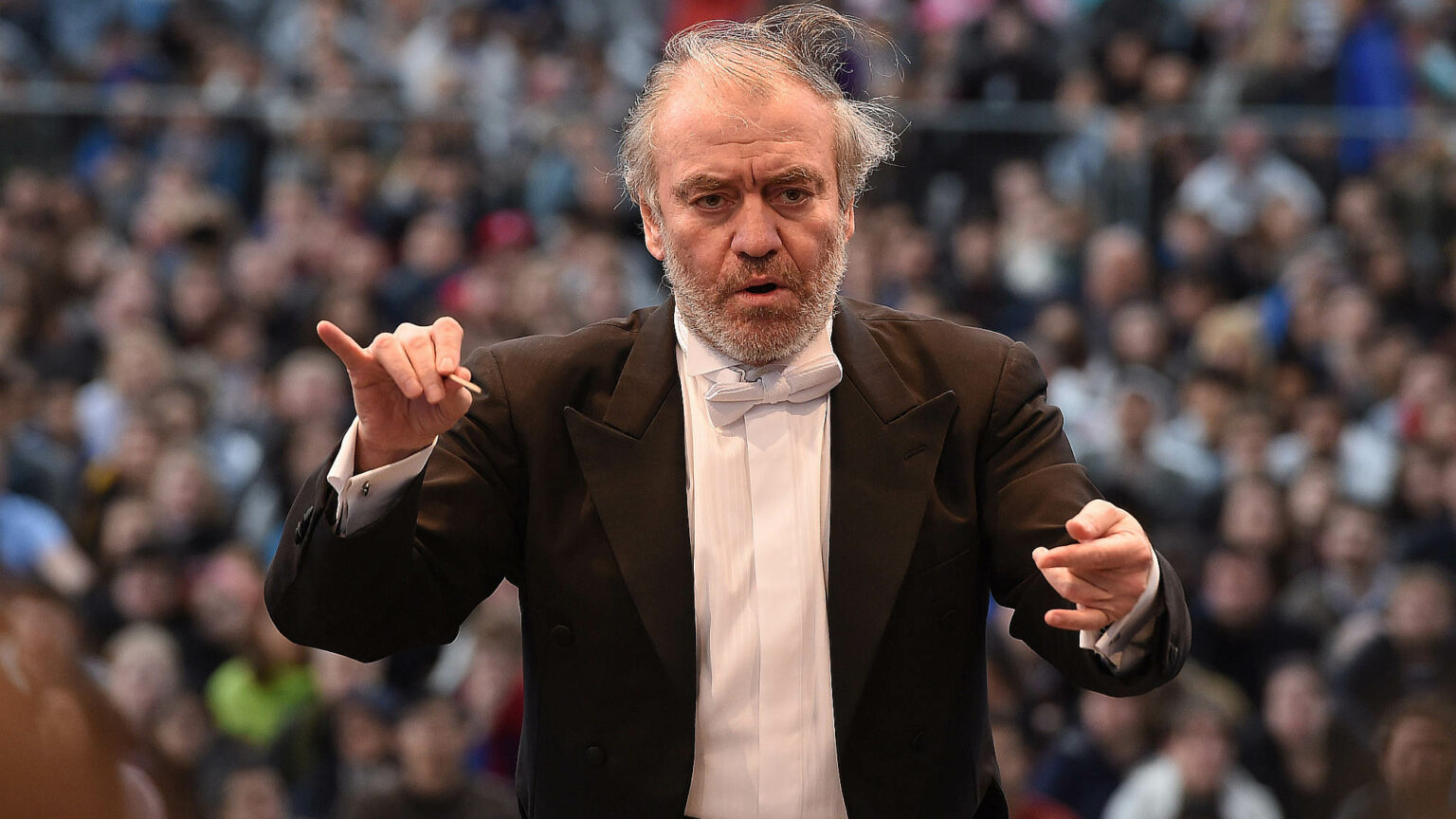

Perhaps the worst excesses of this boycott have been witnessed in the West. A McCarthyist mood has swept our cultural institutions. Star soprano Anna Netrebko has been ousted by New York’s Met Opera over her close links to Putin and past associations with pro-Russian separatists in Ukraine. She has issued a statement denouncing the war, but when the Met asked her to denounce Putin specifically, she refused and was sacked. Conductor Valery Gergiev, a close friend of Putin, has been sacked by the Munich Philharmonic under similar circumstances. He was also issued with an ultimatum: denounce the invasion or pack up your batons. Both were essentially told to take a loyalty oath; their silence taken as proof of their guilt.

It gets worse. Russian filmmaker Kirill Sokolov has family in Ukraine. He has backed online petitions against the invasion. And yet he has still had his new film, No Looking Back, dropped by the Glasgow Film Festival – all because he, like many other filmmakers the world over, has received funding from his government. Then there’s Alexander Malofeev, a 20-year-old Russian pianist, who has had a performance cancelled in Vancouver. He has no links to Putin and had said nothing about the war when his performance was pulled. That, as it turns out, was the issue. Leila Getz, artistic director of the Vancouver Recital Society, said she could not ‘in good conscience present a concert by any Russian artist at this moment in time unless they are prepared to speak out publicly against this war’. Getz later said that the cancellation was due to concerns for Malofeev’s safety. But as her original statement readily conceded, denouncing the Russian government is hardly risk-free for Russian citizens at the moment, either. Just ask the thousands of brave Russians who have been beaten and arrested for protesting against the war.

By contrast, our cultural institutions are gripped by a mix of cowardice and hysteria. What else could explain the decision of the University of Milano-Bicocca in Italy to postpone a course about Fyodor Dostoevsky – all ‘to avoid any controversy, especially internally, during a time of strong tensions’. One of the greatest authors who has ever lived must not be taught for the time being, purely because he is Russian. That Dostoevsky spent time in a Siberian prison camp for belonging to a group who discussed books that were critical of the Tsarist regime gave this particular case a grim historical irony. Thankfully, after international uproar, the university backtracked. But there does seem to be a broader atmosphere of ‘ban first, ask questions later’ where anything Russian is concerned. This is perhaps why the Russian State Opera – which has no links to the Russian state; it’s a British-based company whose name is just a bit of branding – has had a string of performances cancelled across the UK.

Russian artists are not the enemy, just as Russian citizens are not the enemy. To hold them somehow responsible for the crimes of their government is ugly, discriminatory and wrong. This cultural boycott risks playing into Putin’s hands. And it risks impoverishing us in the West – by encouraging us to see a nation that has given humanity untold cultural treasures as some backwater we should have nothing to do with.

We must reject this cultural boycott – and the Russophobia that has inevitably been stirred up with it. It will do precisely nothing to help the people of Ukraine. But as that bloody, senseless war rumbles on for another day, it will eat away, if only a little more, at our shared humanity.

Tom Slater is editor of spiked. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Slater_

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.