The great populist revival

Restrictive Covid measures have stirred another wave of anti-establishment revolt.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

When Joe Biden was elected US president, it was supposed to mark the end of the great populist revolt of MAGA-hats and Brexiteers. Normal service, if a little battered, was to be resumed.

Yet a year later, normal service has not resumed. Major world cities are now wracked by protest movements outside the mainstream. And they are often met by repressive police violence.

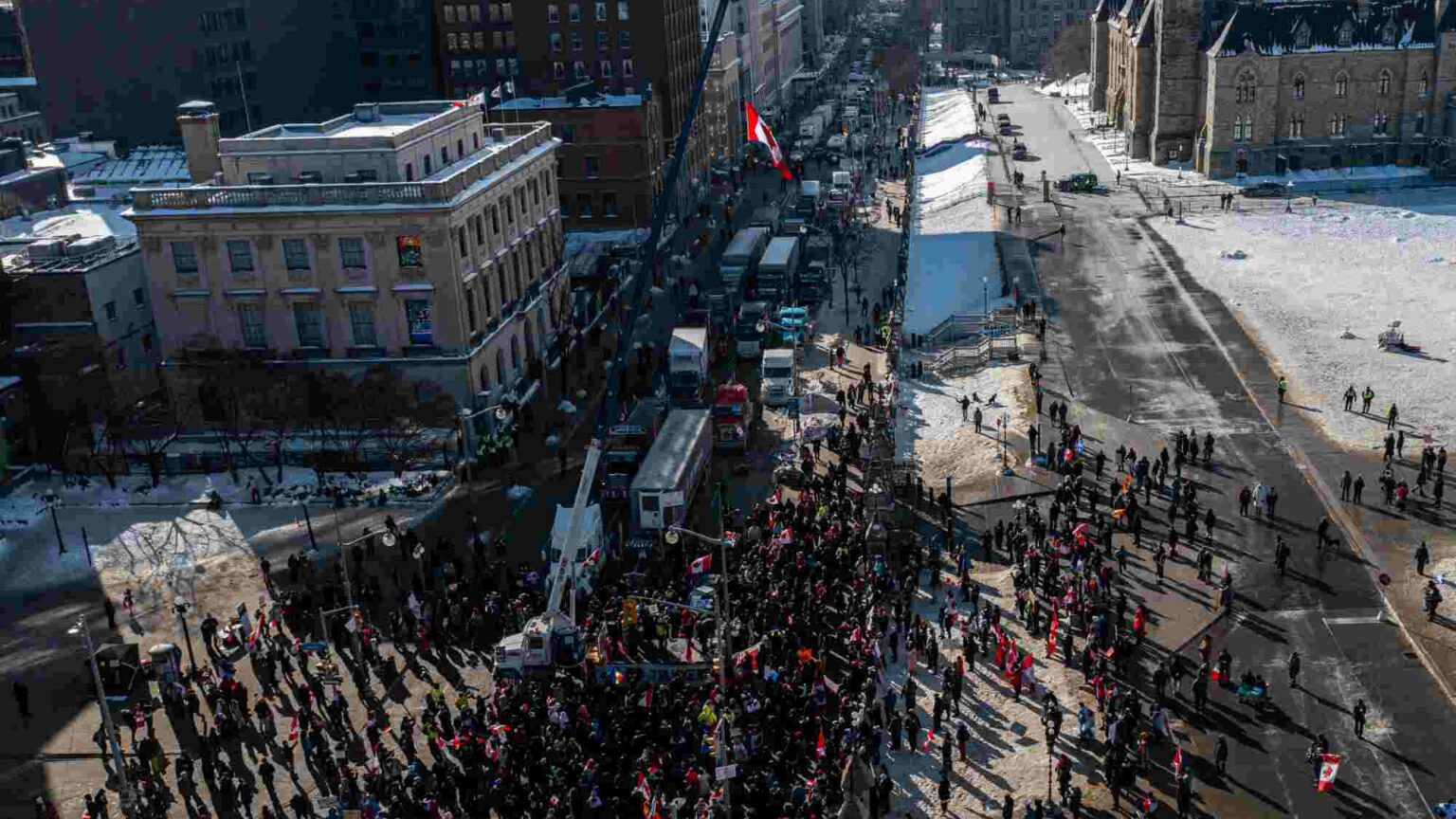

The focal point of many of these protests are the policies that governments around the world adopted to meet the challenge of the pandemic. Over the past couple of weeks, there have been large protests in Helsinki, Brussels, Verona, Rome and Paris. Many of these European cities have faced sporadic protests against vaccine mandates and other measures since last summer. But over the past fortnight, those protests have been galvanised by the example of the Canadian truckers’ ‘freedom convoy’, which drove from one end of Canada to the other, arriving in Ottawa last weekend, in protest against vaccine mandates.

Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau, like most world leaders, embraced the strategy of locking down his country in the face of Covid with gusto. Canadian legislatures declared states of emergency, mask mandates, bans on public gatherings, restrictions on travel and business closures. The particular trigger for the truckers’ protest was the end of an exemption for truck drivers from the need to be vaccinated. The convoy’s journey excited large solidarity rallies in Winnipeg, British Columbia and Ottawa. Perhaps foolishly, Trudeau fled the capital, Ottawa, to avoid meeting the truckers.

It is important to note that none of the protests, either in Canada or in the rest of Europe, could claim to be so popular as to be representative of majority opinion. On the contrary, polling shows that across the world, most people remain supportive of measures to prevent the spread of Covid.

But the protest movements share much with previous populist movements, from the Trump rallies to the European anti-corruption protests of recent years. Pointedly, these are ad-hoc coalitions that are markedly suspicious of mainstream political parties – and the mainstream media. Conspiracy theories abound in these populist movements, as does scepticism towards traditional figures of authority.

There is a longer post-Cold War history of anti-mainstream movements, from the third-party presidential run of Ross Perot in the US in the 1990s to the Occupy movements of the early 2010s. More recently the populist revolt actively disrupted the mainstream political process, with Brexit and Donald Trump’s presidential victory in 2016.

The feature that unites all these disparate movements is that they have all sprung up where the mainstream political parties of the left and right have lost their ideological direction. Without the strong narratives of socialism or free markets to galvanise popular support, political parties have retreated into the technocratic administration of passive publics. The shrinking arena of political contestation leaves a large section of society unmoved and unconnected to government.

So what is the relationship of the Covid lockdowns, vaccine mandates and other pandemic measures to populist movements? It is important to say that Covid was not, as some of the protesters believe, a hoax. This deadly virus has killed more than five million people worldwide and presented governments with a compelling and dramatic call to action. Clearly public authorities that failed to do the best they could to protect their citizens would be failing in their duty.

But the measures that governments did adopt betrayed a pointed distrust of their citizens. They suggested that the public were themselves the danger. People therefore had to be regulated and tutored in how they should behave, as if they were children. Populations were ‘locked down’ and subject to onerous curfews in ways that they had not been since the dictatorships of the mid-20th century. Public debate was suspended in constituent assemblies and public meetings banned. And, latterly, electronic Covid passes have been introduced across Western Europe and in many American cities.

Those repressive measures were not strongly opposed at first because the public was, for the most part, sympathetic to governments’ intention to protect them. So while there were protests against the measures in the first year of the pandemic, these were easily contained and characterised as the work of dangerous eccentrics. The anti-lockdown protest movement was nonetheless interesting precisely because it was completely outside the mainstream political parties.

Moreover, the subsequent anti-vaccine-mandate protests connected to a wider audience than merely those who were sceptical about vaccines. Opposition to repressive measures grew as more people felt those measures to be onerous and disproportionate. That minority who were faced with sackings and restrictions because of their unvaccinated status got a hearing from people who were fed up with the restrictions on their everyday interactions.

In Italy, Austria, Belgium and other European states, where special restrictions on the unvaccinated are especially onerous, protests have become much more confrontational. While these protests are still at odds with majority public opinion, they have proved difficult to contain.

The continuation of populist protests in opposition to specific Covid measures has as many distinctive national features as the national administrations have different policies, and each ought to be examined in its own right. The attempts by campaigners as far afield as Glasgow, Helsinki and Canberra to reproduce the impact of the Canadian truckers’ convoy have a large element of theatre. Still, the continued disorder points to a significant chasm between rulers and ruled. The protest movements have prospered in the void created when political parties coalesced in a singular governing establishment, united in a common programme of regulating the pandemic through administrative – and at times coercive – measures.

The prospects of further disorder are considerable. It does seem likely that the world economy is facing a difficult period, with rising fuel prices, inflationary shocks and labour-market tensions. That protesters in Helsinki and Istanbul raised new grievances over fuel prices is an indication of what might be to come.

The mainstream political parties are more out of touch with their publics than they were before the lockdowns, and their ability to negotiate change is far weaker. The likelihood is of more and greater populist protests to come.

James Heartfield’s latest book is The Blood-Stained Poppy, written with Kevin Rooney.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.