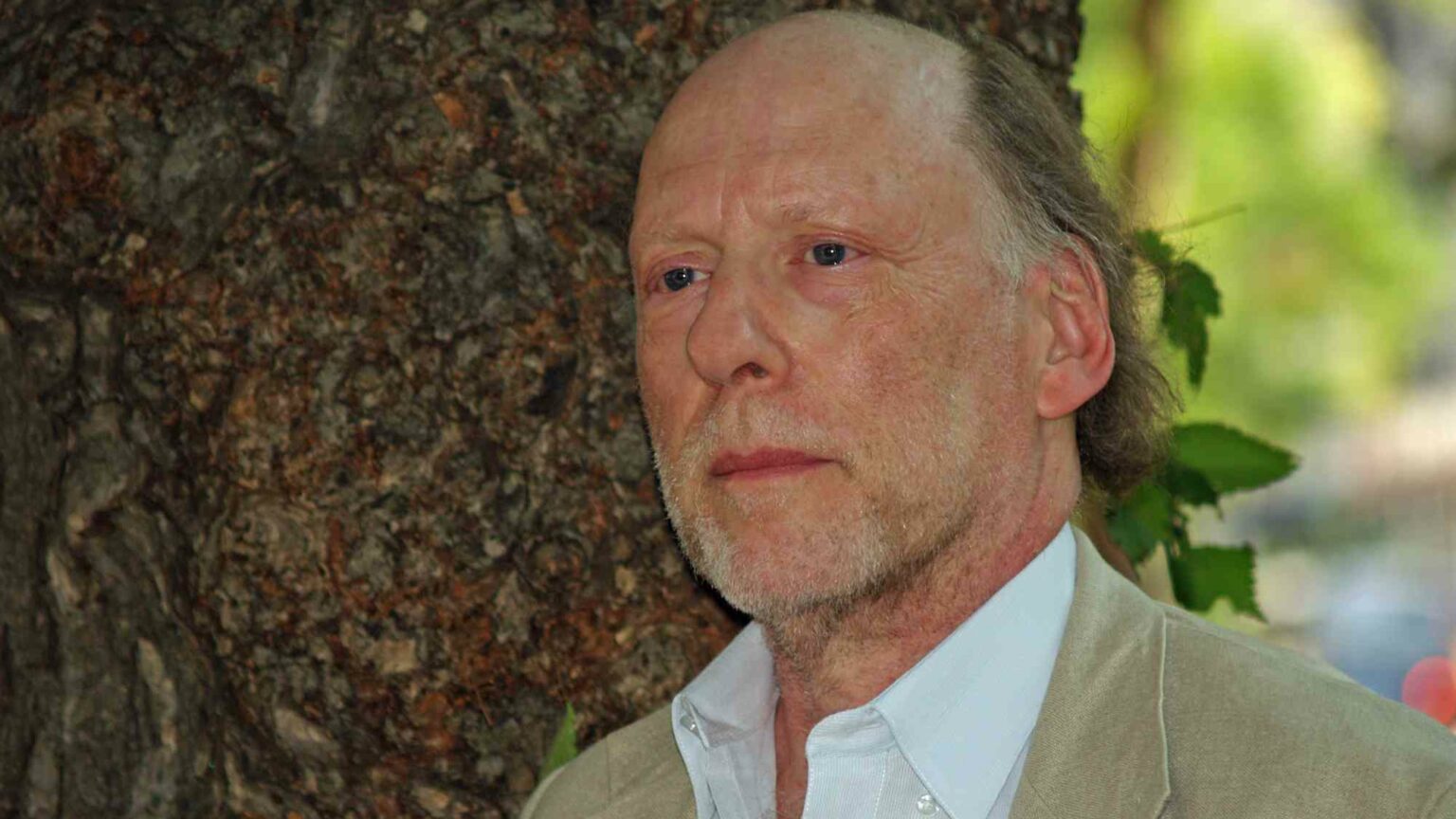

Farewell Todd Gitlin, a radical democrat to the end

Unlike so many 1960s radicals, Gitlin never succumbed to the lure of identity politics.

Todd Gitlin, who died on Saturday aged 79, was one of the last 1960s radicals standing. Unlike so many of his associates, he seemed to retain an active commitment to the radical democratic ideals he upheld in his youth.

Gitlin personified the New Left politics of the 1960s. He was an early president of Students for a Democratic Society, which became arguably the most important radical movement in the US at the time. And he played a prominent role in organising demonstrations against the Vietnam War and the Apartheid regime in South Africa.

During the 1960s, Gitlin was full of heady optimism. As he was later to recall, ‘what moved me most about the SDS circle’ was that ‘everything these people did was charged with intensity’.

Indeed, this intensity led many members of the SDS, including Gitlin, to embrace a voluntaristic and often very personal orientation towards political life. As Gitlin wrote in The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage (1987), this new politics centred on ‘a passion to make life whole: to bring political commitment into private life, to make private values count in public’. The aim was to overcome the ‘treacherous schism between public postures and private evasions and hierarchies’.

The politicisation of private life and the emotional needs of the self – writ large in Carol Hanisch’s 1969 essay ‘The Personal is Political’ – was one of 1960s radicalism’s most significant contributions to politics and culture. It served, effectively, as a precursor to identity politics.

Gitlin was aware of this connection, between the personalisation of politics and its crystallisation into identity politics. Indeed, the first usage of the term ‘identity politics’, recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary, was in the 1973 Irving Howe-edited book, 1984 Revisited, to which Gitlin himself contributed.

Throughout his life Gitlin tended to underestimate the power of identity politics. Writing in Dissent in 1995, he argued that political correctness was not a phenomenon of lasting significance. The ‘heyday of PC and the adversary culture is over’, he concluded.

Gitlin clearly wanted the ‘heyday of PC’ to be over. He was concerned that identity politics had significantly weakened the left as a political force. In The Twilight of Common Dreams: Why America is Wracked by Culture Wars (1995), he warned that while the Republicans had gained power in Washington, the left was ‘marching on the English department’.

Today, it is not simply English departments that have fallen prey to wokeism of course. Virtually every significant institution in the Anglo-American world is dominated by identity politics.

To his credit, Gitlin, unlike many of his associates in the SDS, remained critical of the divisive consequences of identity politics. In July 2020, he was among the signatories to a high-profile letter to Harper’s Magazine, which condemned cancel culture and the growing tendency to shut down and punish those who hold politically incorrect views.

Gitlin’s hostility to cancel culture showed that he retained some of the spirit of his youthful democratic radicalism. Indeed, he steadfastly refused to conform to the illiberalism of the left. So, although he was critical of Zionism, he actively opposed the anti-Israel Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement. For this, he was denounced by woke activists as a ‘liberal Zionist’.

To the end of his life, Gitlin’s political integrity shone through. He was a man of honesty and possessed a principled non-conformism so rare among leftist activists today. Though he perhaps never fully grasped the contours of the world that emerged from the 1960s, he intuited that there was something fundamentally wrong with identity politics.

His commentaries on public life will be sorely missed by free-thinking people everywhere.

Frank Furedi’s 100 Years of Identity Crisis: Culture War over Socialisation is published by De Gruyter.

(1) The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage, by Todd Gitlin, Bantam Doubleday, 1993, p365

Picture by: David Shankbone, published under a creative-commons licence.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.