COP26: where democracy goes up in flames

A parliamentary delegate at COP26 reflects on a dull, debate-free gathering.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

On my way to Glasgow for COP26, as part of a delegation from Iceland, I stayed at a hotel in London. While there, I turned on the news and started switching through the channels. All were carrying the same back-to-back coverage of the End of Days.

Watching these endless news reports ahead of my trip to COP26, it appeared that its mission was not just to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions. It was also to tackle institutional racism, gender inequality and just about every cause you can shake an ecologically grown stick at. There was nothing that tackling climate change seemingly couldn’t achieve.

The next day, while waiting for the train to Edinburgh, I decided to familiarise myself with a proposal we were to debate and vote on. This was a draft declaration from the Inter-Parliamentary Union, which was to be ratified by MPs from different parties representing almost every parliament in the world.

The authors of the proposal had clearly set out to win the agreement of the world’s parliamentarians through an extraordinary exercise in apocalyptic hyperbole. It was all there – descriptions of various natural catastrophes to come and the destruction of ‘decades of economic and social progress’.

As the document explained, CO2 emissions don’t just affect the weather. They also impact on equality, social justice and almost every issue of concern. Here’s a sample:

‘Concerted climate action can be key to securing stability, avoiding or mitigating conflict, preventing climate-induced migration, and resolving national and regional conflicts and crises. Preventing further climate change can also be a crucial factor in securing a new and more inclusive wave of multilateral participation, while driving support for the socio-economic advancement of developing countries.’

In short, it seems reducing CO2 can pretty much solve all the world’s problems.

After explaining that climate change is a great threat to global food security, as it ‘reduces crop yields and results in food shortages’, the document states: ‘At the same time, agriculture is one of the main drivers of biodiversity loss and climate change, adversely affecting food security.’

We at COP26 were not only expected to condemn the Industrial Revolution, as everyone from Boris Johnson to Greta Thunberg had been doing – we were also supposed to damn the agricultural revolution, too?

Among the suggestions parliamentarians were asked to consider were ‘people-led “climate committees”, working in cooperation with non-governmental organisations, grassroots movements, and climate activists to help underscore the value of parliamentary voices’.

It was time to close my laptop and leave for the train station.

At Kings Cross there was an artificial tree where commuters could hang little notes describing their environmental pledges. This was provided by a Japanese high-tech conglomerate. I wrote my own little note: ‘I will advocate improving the environment through innovation and technology rather than taxation and restrictions so that more people can buy your products.’

The trip to Edinburgh went according to plan, inasmuch as no trees fell on the tracks – although that did deprive me of an opportunity to post something on Facebook.

The next day I showed up late for the meeting of parliamentarians from around the world. I had taken the wrong train and missed some instructions on the criteria for attending, but that was on me. I also took the time to eat a Scottish beef burger, having read that delegates at COP26 would primarily be fed vegetarian food.

When I arrived I was informed that there was little scope for debate. The day-long agenda was primarily divided into three recurring categories: ‘advocacy sessions’, ‘inspirational talks’ and ‘expert opinion’. The parliamentarians were told that if they wanted to make a point, they should have sent an email.

I became thankful for the time spent on taking the wrong train. Before long, I started to sympathise with Joe Biden’s drowsiness a few days earlier.

Some of what passed for ‘expert opinion’ was at least revealing. For instance, a spokesman for the low-lying island state of Tuvalu was understandably worried about rising sea levels. He told us that his country had been trying to mitigate the effects and had received funding for a five- to six-year-long project to create seawalls. That was six years ago and not a single brick had been laid. Yet half of the funding had already been spent – on consultants.

When the time had come for the world’s parliaments to respond to the meeting proposal, there was no room for discussion and certainly no time for a vote, despite this being a gathering of people’s representatives. The document was declared adopted and we were told to go and tell our governments to abide by it.

The next day I went to the so-called blue zone. It was enormous, filled with tens of thousands of people and very, very noisy. The general mood and atmosphere seemed much more hectic than in Paris in 2015. Back in Paris, people casually walked between the pavilions, where they could listen to lectures or talk to the hosts, receive printed material, and put it in complementary carry bags made from hemp.

COP26 seemed frenzied in comparison. There were speakers talking to a few guests in every corner, but you had to borrow noise-cancelling headphones to hear them. Few dared to offer printed material and I couldn’t find a single hemp bag. The crowds seemed very serious but also very enthusiastic.

There were water fountains all over the place, but no cups. You had to have your own container. I found a desk where they were handing out water bottles and asked whether I could have one. A lady standing in front of shelves full of water bottles asked to scan my pass. After doing so she looked at me stony-faced and said that unfortunately they had no more water bottles.

Had I been blacklisted? After all, I had written a critical article on COP for the Spectator the week before. I took two steps to the right and asked the next young lady whether I might possibly have one of the hygiene kits that were also on offer. ‘Certainly’, she replied, ‘and wouldn’t you also like a water bottle?’.

Fully hydrated, I continued to brave the tents, corridors, halls and pavilions of COP26. There were some interesting exhibitions and companies doing fascinating things. But they were all telling the same stories – the same stories that were being told on the news about how human industriousness was increasing inequality, natural disasters, racism, hunger, war, and so on.

What was entirely lacking was debate. I was told that was because we were past that. ‘The Science’ was clear. There was nothing to debate.

But on my way home from Glasgow, I wondered whether accepting that climate change is a huge problem does not at least call for a debate on how to solve it? And if it doesn’t, what does that tell us about climate change as an issue?

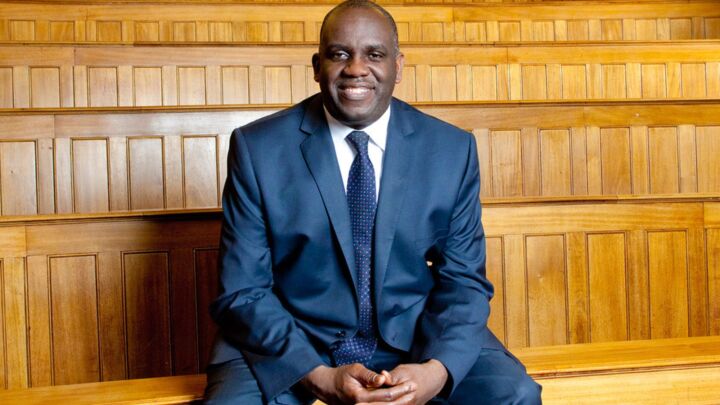

David Gunnlaugsson is a former prime minister of Iceland.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.