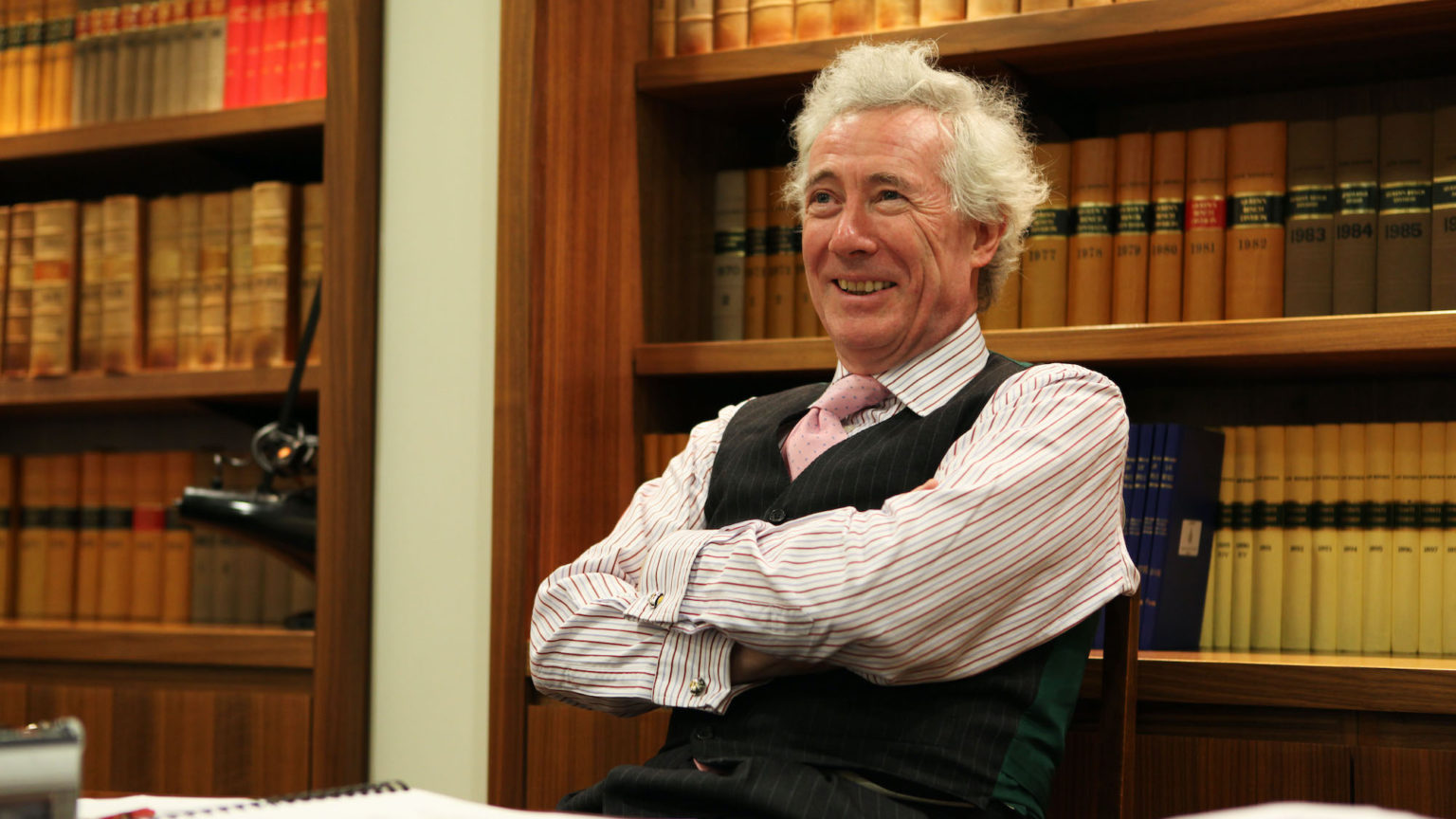

We need more Jonathan Sumptions

His principled defence of liberty during the pandemic has been a lifeline to many of us.

I went to Oxford University last night to see Jonathan Sumption give a lecture in defence of democracy.

As he said himself, the very idea that such an apologia was necessary would, even 20 years ago, have been thought absurd. It would have been patronising, redundant to the point of being self-congratulatory, oratory in easy mode. An exercise perhaps valuable if aimed at a sixth-form college, or a gathering of those recently arrived from tyranny overseas and seeking to apply for citizenship, but not required for anyone to the manner born, let alone the great and good and wonky of Oxford University.

But, as the popular Twitter expression of weary resignation has it, here we are.

Sumption produced evidence, in the form of various UK opinion polls and European elections, that a growing number of people are willing, keen even, to sacrifice liberty to a state that offers protection, especially from pestilence and contamination. That many would prefer a ‘strong leader’ who ‘breaks the rules’ and ‘gets things done’. That many of the principles of liberal, representative democracy turn out to be contingent, and subject to Groucho’s famous money-back offer.

And so a defence of democracy is now very much a defence against a gathering storm. And to be fair, as John Stuart Mill said, all ideas, and especially those that seem in their pomp to be most comfortably self-evident, need challenging regularly, if they are not to atrophy. So perhaps it is as well that democracy can no longer take its moral and pragmatic superiority as read.

Sumption’s was the fourth and final Scruton Memorial Lecture in this inaugural season. He followed the likes of Tom Holland and Niall Ferguson, both of whom I would have camped out to see, had I not been committed to taking my daughter to an IMAX to see Dune. Well, that too had something to say about the fragile nature of any once impregnable political system – and indeed the seductive emptiness of big oval tables beneath which hand signals and passed notes furtively contradict spoken commitments and oaths. But the judge built his case more carefully, and with less recourse to green screen.

Sumption was a good fit for these lectures, to say the least. Seeing his name annexed to Scruton’s was instinctively satisfying, and not only because as the years have advanced he has remained sharp, considered and glinty-eyed with informed scepticism – as Scruton did before his death last year. Nor, to paraphrase Mill yet again, because Sumption’s name is among the few the mention of which after Scruton’s would not amount to anti-climax. But also because a superimposition / portmanteau of the two gets us very close to the affectionate nickname by which the lion-maned old campaigner was known to those of us who valued his courageous, if somewhat quixotic, campaign against lockdown and other flavours of encroaching autocracy these past two years – truly, Scrumptious.

Lord Scrumptious was an extraordinarily important figure to those who were alarmed by the speed with which the Maginot Line of traditional Britannic liberty collapsed in spring of 2020, yet were equally aware that the resistance seemed to be comprised chiefly of a motley, often dispiriting assembly of professional provocateurs, recidivist attention junkies and outright cranks. I had a number of friends who shared my serious concern as ‘three weeks to flatten the curve’ became an ever-more comprehensive constraint of ancient individual rights. Yet we felt little inclination to join forces with Piers Corbyn, David Icke nor even to be honest Desmond Swayne, even to do battle with an elected government which had literally stood on the issues of independence and sovereignty at almost any cost.

Sumption was able to articulate our concerns without recourse to words like ‘plandemic’ and ‘pre-conditioning’. He eschewed talk of the New World Order, of 6uild 6ack 6etter, and as comedian Rich Hall put it, of the idea that the vaccine was a ‘liquid sim card’ developed by Bill Gates to track your every move. The vocabulary of conspiracy in other words – and a scenario our digital Cassandras shared urgently on their location-enabled smartphones behind the enemy lines of Facebook and Twitter whenever they could get a signal.

Instead, he reminded us forcefully of the stickiness of authoritarian measures, and the illusion that a bath plug can and will be pulled when the emergency has passed and the filthy waters of the state will simply drain away. He reminded us that, as well as corrupting, power ratchets, and measures once granted in extremis are rarely shrugged off in tranquillity.

He was one of a few, if not a happy few – among the others I would include Peter Hitchens, whom no one would accuse of being happy nor indeed activated by any thought of banding with brothers. But Sumption and Hitchens seemed to see something distinctly unwelcome in the clouds that were massing on our horizon. Massing over our rights to freedom of assembly, freedom of association, freedom of passage. All these have seemed at one time or another, to many millions of people, natural laws, too big and too fundamental to repeal even should the state deem it necessary. Until one day, suddenly, they weren’t.

Whether we will emerge from this pandemic with our pre-existing liberties intact remains to be seen. But there seems little doubt to me which side most of the pressure is coming from, and the importance of setting our shoulders to the other.

It was a good lecture, and the discussion with Charles Moore afterwards further illuminated Sumption’s views. But perhaps most haunting, chilling even, though I think quite unintentionally, was the summing up provided by the chancellor of Oxford University, Chris Patten. Patten’s tone was avuncular and robust in defence not only of democracy but also of the Conservative government of which he was a notable part. He has of course had a long and very distinguished career. But he remains for me the man who more than anything else was the avatar for our obligations to Hong Kong, over whose handover to the CCP he presided in 1997. I suspect for anyone paying attention, I hardly need finish this thought out loud. It can happen here.

Democracy, like many of the most precious things, which are themselves a source of strength – a happy home, good health, faith, hope and charity – can prove to be suddenly, catastrophically fragile when caught at the wrong angle – most often from within. We must celebrate and support voices that strengthen our own resolve to defend it, men like Jonathan Sumption, on whom so much, so much, depends.

Simon Evans is a spiked columnist and stand-up comedian. He is currently on tour with his show, Work of the Devil. You can buy tickets here.

Picture by: Alamy.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.