The rise of the West

Patrick Wyman's The Verge explains how 19th-century Europe eclipsed East Asia.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

For most of human history, the centre of the world was to be found to the east of Europe – in the early states of the Near East, the many versions of the Chinese Empire, and the trade networks that criss-crossed the Indian Ocean.

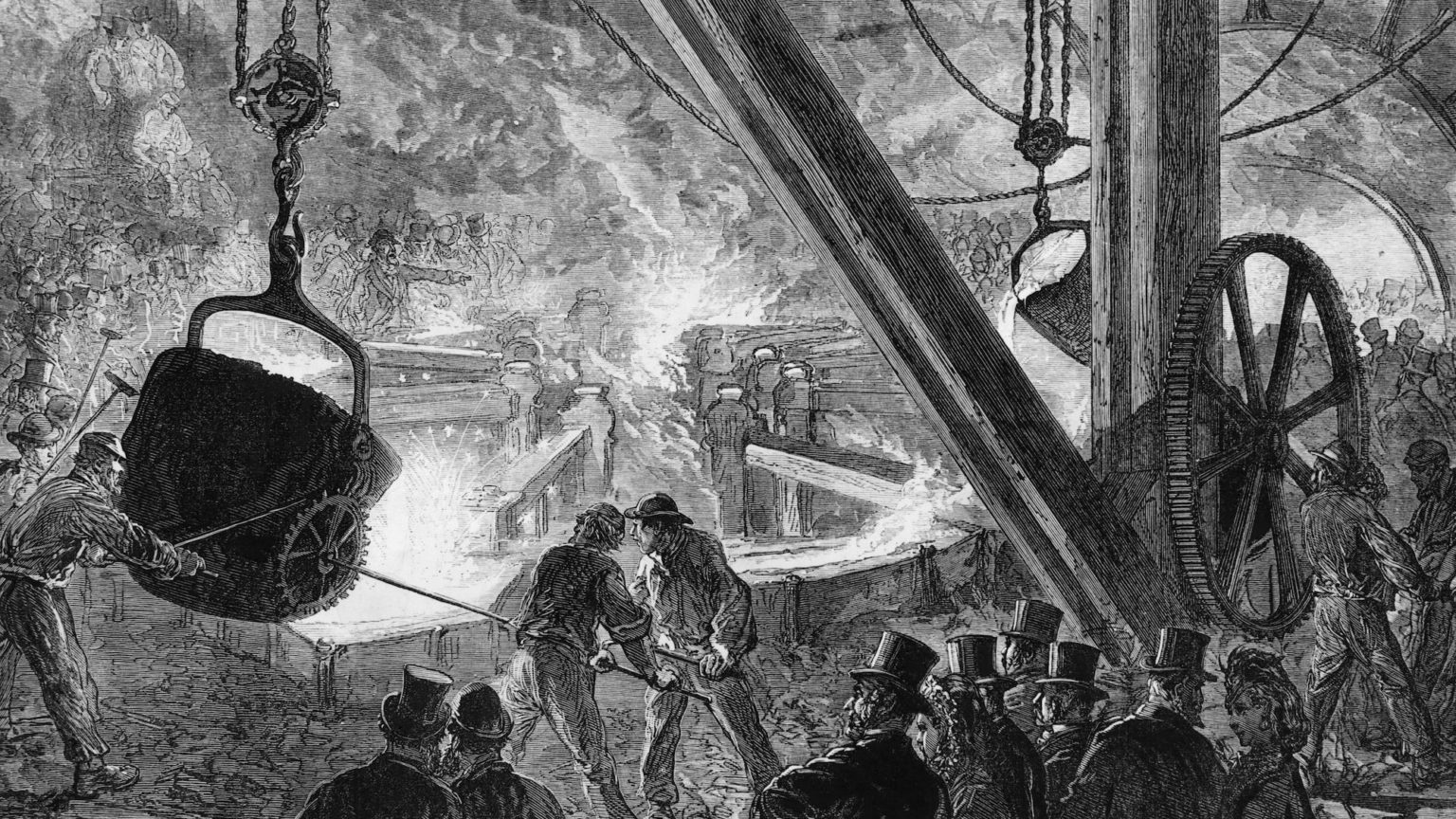

Yet at some point over the past 500 years or so, all that changed. European states became more powerful, gobbling up parts of the world. And, following the Industrial Revolution, their economic output began to skyrocket, especially in Britain and the Netherlands.

By the 19th century, East Asia, hitherto the centre of the world, had been outpaced by Western Europe. This development is known as ‘the Great Divergence’.

How and why this happened is one of the perennial debates of history and economics. Did the multi-state system of Europe, encouraging competition and conflict, mean that Europe developed the most advanced forms of warfare? Or did the Renaissance and the Enlightenment pave the way for Europe’s advance? Or were its legal and political structures particularly well suited to the growth of private enterprise?

It has proven a long and interminable debate. The latest contribution to it comes from Patrick Wyman, with The Verge: Reformation, Renaissance and Forty Years that Shook the World.

Wyman claims that the origins of the Great Divergence lie in a four-decade period, between the 1480s and the 1520s. To tell the story of this tumultuous era, he explores the roles of famous figures, like Martin Luther and Christopher Columbus. But he also delves into the roles of the more obscure ones, like the German knight, Götz von Berlichingen, who played a key role in the evolution of warfare.

Wyman begins The Verge with the event that closes his four decades of upheaval – the Sack of Rome in 1527. An army composed of Spanish regulars and German mercenaries, and ostensibly serving Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, breached Rome’s walls. They then engaged in an orgy of violence and looting – and many of the German mercenaries, full of Lutheran zeal, attacked Catholic clergy and religious buildings.

For centuries, Rome had been the religious and cultural heart of Europe. And suddenly it had been humbled, its riches plundered, and its religious leaders killed or forced to flee. This event, writes Wyman, would have been ‘unimaginable’ four decades prior. It was, he writes, ‘the culmination of a tidal wave of upheaval, driven by the convergence of a multitude of profoundly disruptive processes’.

Wyman outlines this convergence as follows:

‘Voyages of exploration, expanding states, gunpowder warfare, the proliferation of the printing press, the expansion of trade and finance, and their cumulative consequences – religious upheaval, widespread violence and global expansion – collided, interacting with one another in complex and unpredictable ways.’

With that, ‘the path that led to the Great Divergence’ had been prepared. In other words, these 40 years of political, cultural and economic revolution in early 16th-century Europe fuelled the rise of the West during the 19th century.

None of this would have been possible, however, without Europe’s unique economic institutions. After all, long voyages of discovery, sophisticated bureaucracies and the development of the printing press were all capital-intensive. They depended on ‘substantial amounts of money for initial financing and even more to sustain them’.

This is where Europe’s peculiar attitude to credit comes in. As Wyman explains, a willingness to provide credit requires an enormous amount of trust between creditors and debtors. And it was the existence of this trust, argues Wyman, that ‘allowed Europeans to pour increasing amounts of capital into these expensive processes’.

Of course, credit and finance existed in ancient times. What made Europe’s approach different, however, lay in its experience of the Great Bullion Famine in the mid-15th century. Wyman argues that, because of the lack of physical coinage due to the exhaustion of silver mines, Europeans had to find ‘ways of working with little to no coin’. And this led to working arrangements based on trust.

This meant that creditors were more likely to lend money because they trusted that they would eventually get it back. They didn’t think profits were guaranteed or that there was no risk. But they were used to working on the basis that the debtor, often personally known to them, was good for his word.

Such an analysis is typical of The Verge. It seeks to reveal the workings of an age, fuelled by economic and cultural forces, and fashioned by the actions of individuals, great and humble. Wyman’s overarching explanation for the Great Divergence and Europe’s ascent is not entirely convincing. But The Verge contains plenty of insights and incorporates them into a compelling narrative. It makes for an engaging work of popular history.

Tom Bailey is a financial writer.

The Verge: Reformation, Renaissance, and Forty Years that Shook the World, by Patrick Wyman, is published by Twelve. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

A world gone mad – with Brendan O'Neill and Julia Hartley-Brewer

Wednesday 22 September – 7pm to 8pm

Tickets are £5, but spiked supporters get in for free.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.