The ‘pingdemic’: another mess of the government’s making

The NHS app was a good idea. But now it’s wreaking havoc with the economy.

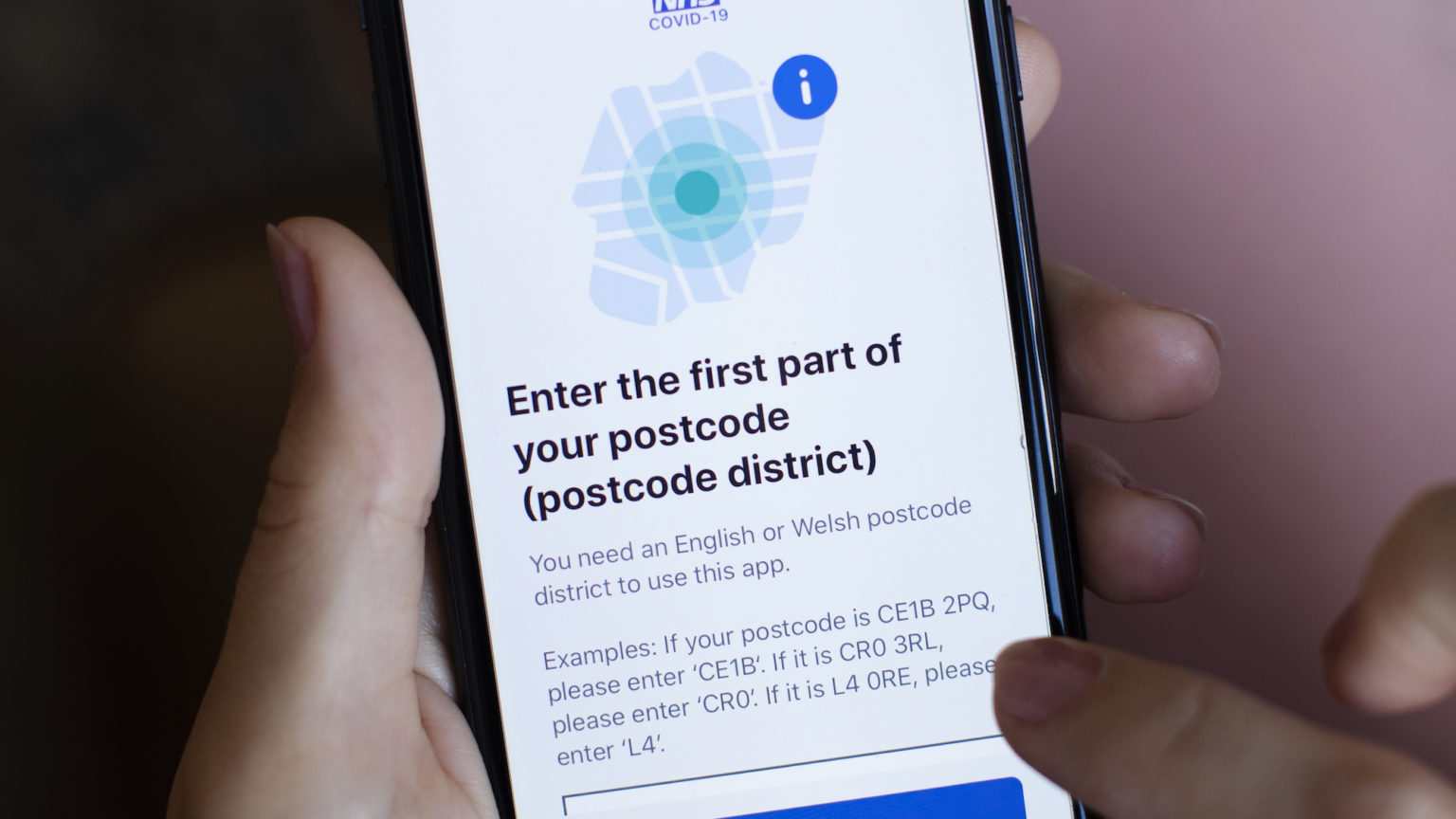

The NHS digital contact-tracing app is creating a pandemic of alerts – a pingdemic – and this has serious consequences for the economy. Hundreds of thousands of workers have been told to self-isolate and stay off work, causing havoc in manufacturing, in hospitality and even in the sacred NHS.

It’s a perfect embodiment of the government’s fearful and ambiguous implementation of ‘freedom’. Do you recall how we were only ‘15million jabs from freedom’ back in January? That same week, the health secretary promised we could ‘cry freedom’ when the most vulnerable had been vaccinated? Eighty-one million jabs later and Freedom Day has not only been delayed once, but it will also be watered down significantly. The government would really prefer to let restrictions continue, but without being held responsible for them – hence it is issuing swathes of last-minute Covid guidance to pass the buck elsewhere. Cake-ism, in other words.

Inside your smartphone, the contact-tracing technology is doing exactly what it was designed to do. But that’s only half the story. A ping from the contact-tracing app today does not mean what a ping meant in January. The app’s policy is still set as if we were back in the fearful days of lockdown, when an alert really might have signalled a significant danger to at-risk groups. Back then, suppression of infection was the primary policy goal. But the app’s policy and its alerts haven’t been updated to reflect that the population has now largely been vaccinated. The risk has changed, and yet the pings continue, like a Second World War air-raid siren that keeps going off long after VE Day.

The public initially adopted the contact-tracing app with great enthusiasm last year – the British are consistently among the most enthusiastic technology-adopters in the world. It reached over 20million downloads by November. But now we are now deleting the app en masse. Half a million people uninstalled the app last week. I was one of them. Many more will have deleted it this week now that the pingdemic is in full swing.

This chaos only undermines the public’s trust in what is an imperfect but nevertheless very useful tool. How useful? Well, you can’t really do ‘test and trace’ effectively without it. As I wrote in the Telegraph at the end of last year, a respiratory virus moves too fast for conventional manual test and trace to work – something NHS Test and Trace has been loath to acknowledge. Research by epidemiology teams at both the University of Utrecht and Imperial College suggests that if test and trace is manual, then it’s largely a waste of time. If it takes two days to confirm a positive test result and to tell someone to isolate – a typical delay incurred by posting results to a PCR Lighthouse Lab – then the impact on the R rate is negligible. Manual tracing is also expensive and fails to reach many of the infected person’s contacts. And to have any impact at all on the R rate, compliance must be very high. Of all these factors, speed is the most important, and digital contact tracing is really the only way to achieve it.

Digital really can make a difference, as the early trials the NHS conducted on the Isle of Wight confirmed.

You may well ask, why can the volume and frequency of notifications not just be adjusted to reflect your own personal risk assessment? Why can you not set notifications to mute if you’ve been double vaccinated? Alas, the government ceded control over Bluetooth contact-tracing technology to Google and Apple last year, after privacy campaigners advised them that this was the only way to gain the public’s trust. Campaigners eventually succeeded in getting the NHS to abandon its own app and to use the ‘decentralised’ model pushed by the Big Tech duopoly because the Apple and Google model retains your location history on your phone.

Alas, no national public-health authority that has based their app on the Big Tech framework can now fine tune the underlying system. The result is an app that doesn’t know who you are, even if you voluntarily wish to reveal that information, as many do (and have done). And to rub salt in the wound, that ‘privacy-protecting design’ was no help when it was discovered that Google left everyone’s entire contact-tracing location history in an easy-to-read log file accessible to any Android developer. Google didn’t fix the bug for months. So much for ‘decentralised’ as a magic sword.

The primary cause of the pingdemic is not really the technology. It is the much more familiar story of a government that basked in high approval ratings whenever it adopted authoritarian policies, but is now unable to make the case for freedom when restrictions are no longer needed, as it fears being castigated by the public-health technocrats and the media. A government that had confidence in us, and confidence in itself, would have recognised that a coercive klaxon is the wrong tool for today, long before the pingdemic erupted.

Andrew Orlowski is founder of the research network Think of X and a columnist at the Telegraph.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.