Inside Story: Martin Amis exposed

Amis' best work for years blends fact and fiction to revelatory effect.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

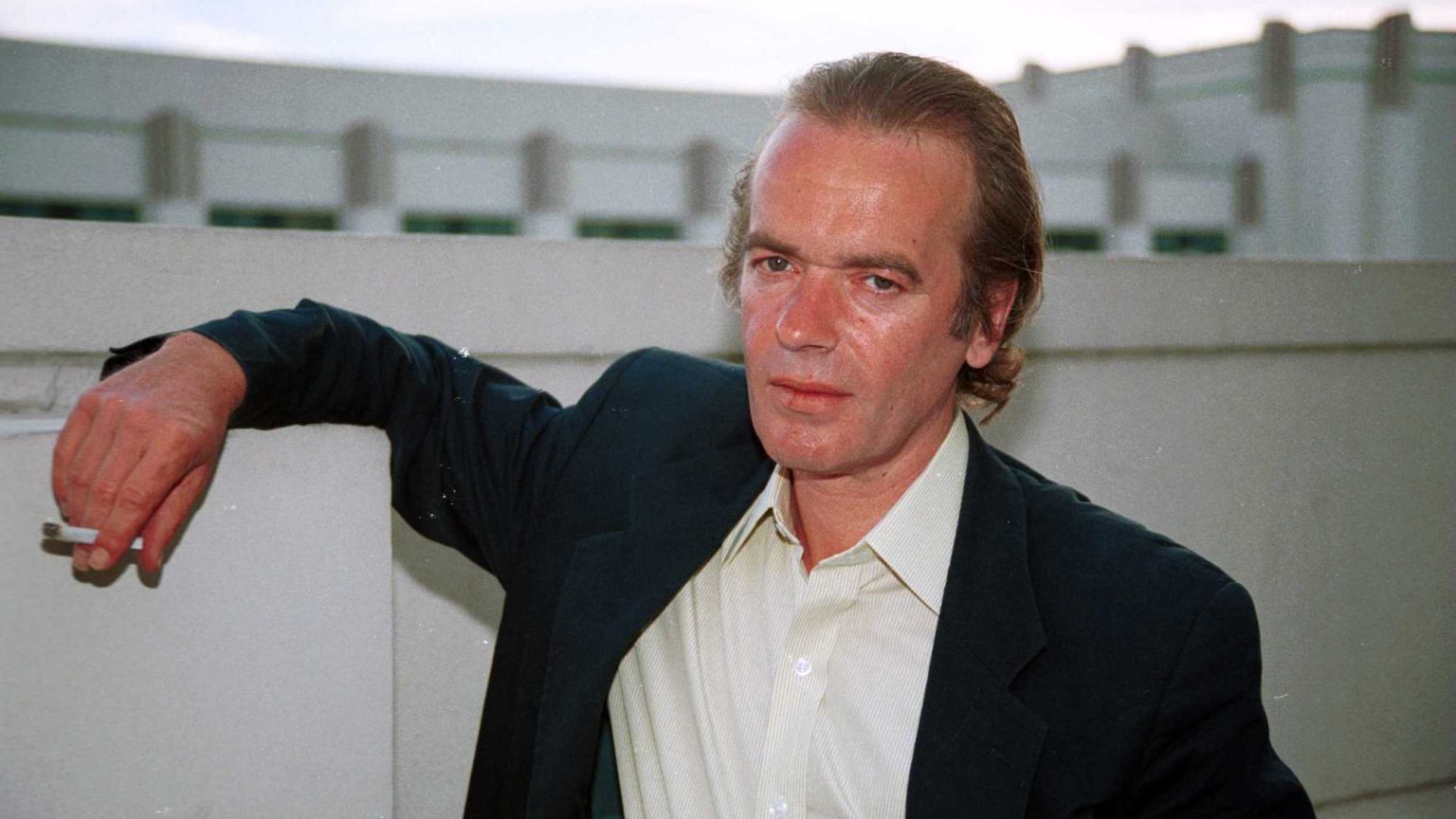

So, a new, unusual ‘novel’ by a big beast like Martin Amis – where to start? Well the cover of Inside Story tells us something. The back looks like a lost promotional poster for Trainspotting, full of dictums about what life is and what life isn’t. And the front? It’s a luminous black-and-white photo of Amis and his friend Christopher Hitchens in their youthful prime.

The combined effect of all this suggests maybe a manifesto on how to live and / or some kind of memoir. Yet in block capitals on the front cover, it still asserts that this is ‘a novel’, despite the real-life content. Indeed, Amis plays with our expectations throughout as to just what this work is. Thus on page 30 he states: ‘This novel, the present novel, is not loosely but fairly strictly autobiographical.’ Perhaps Inside Story should be considered a type of Bildungsroman then? Or maybe it is simply something closer to what Amis himself once called a ‘baggy monster’, a ‘subgenre of long, plotless, digressive and essayistic novels’?

Either way, Inside Story is something particular, something unique. Much earlier on, in the introduction, which he calls ‘Preludial’, Amis asserts his own belief that if you’re in the business of writing novels, as opposed to poetry, autobiography or even ‘impressionistic memoirs’, you are uniquely ‘exposing who you really are’. And maybe that is what Amis is doing here. He even comes up with a new categorisation of his own (initially to describe the writings of DH Lawrence and Saul Bellow), which may help us define Inside Story: ‘life-writing.’

He does admit that ‘the trouble with life-writing, for a novelist, is that life has a certain quality or property inimical to fiction… it is shapeless’. But he tells us early on that he is nevertheless ‘excited by the challenge’ of trying it out.

To this end, Inside Story has three main protagonists, or ‘principals’: a poet, a novelist and an essayist. The poet is Philip Larkin; the essayist is Christopher Hitchens; and the novelist is Saul Bellow.

Interestingly, it is through Amis’ filial relationship with Bellow, lovingly and painstakingly described, that we come to Israel and Amis’ unfashionable and straightforward defence of its right to exist. While much of the book reads as the memoirs of an unabashed liberal-cum-libertine (with eminently predictable views on Brexit and Trump, for example), the tenor of his writing here about Israel, the Holocaust and 9/11 reveals a different Amis, and is the source of some of the book’s best passages.

There’s a freshness and immediacy when, for example, he describes a 1987 trip to Israel to speak at a symposium on Bellow. There he writes of his ‘immediate baptism in a riptide of urgencies’.

Partly it is just damned good travel writing. It is also a gripping portrait of a nation – its neuroses, its intellectuals, its soul. It is no coincidence that it is in this chapter that Amis grasps just what it is that allows Bellow to bring the enduring qualities of art to life-writing: the ability to see the sacred in the profane. The Israel section, reading like a piece from Time magazine or Newsweek at their height, highlights how little we read about Israel today in the UK that goes beyond caricatured and lazy notions of a malign and illegitimate entity.

The ‘three principals’ each play the role of father figure throughout. Amis writes of Hitchens giving him the solid and peculiarly catholic advice of ‘avoiding the occasion of sin’ prior to his first marriage in the early 1980s; and he steers Amis away from the ‘moronic inferno’ of his early adulthood. It is also Hitchens who first introduces Amis to Bellow’s work, giving him the ‘red Penguin of Herzog’ in 1975.

Bellow, in whom ‘the religious impulses survived’, was also certainly a kind of father. After Kingsley Amis’ death in 1995, Amis would say to him a year or two later, ‘As long as you’re alive, I’ll never feel completely fatherless’.

And Larkin? Well, that is more complicated.

One of the peculiarities of this book is that while it does indeed read often as a memoir, and the majority of the principal characters are assigned their real-life names, both Amis’ wives, all of his children, and his brother and sister are referred to by names which are not theirs. Amis’ sister Sally, for example, is referred to as Myfanwy (a name which Larkin obsessives might note is that of one of the female protagonists of his early novella Trouble at Willow Gates). And then there is a certain Phoebe Phelps, an alias of one or more of Amis’ lovers during the 1970s.

It is through Phelps that Inside Story leads us to the extraordinary revelation that Philip Larkin could possibly be Amis’ father. This is based on the reasonably well-known fact that Larkin was always close to Amis’ mother, Hilly Bardwell, Kingsley’s first wife. Clues may be discerned in a letter Hilly sent to Larkin in March 1950: ‘I’ve got a weekend off in April when I shall be going to London. I dream that I’m meeting you there, and that we’ll have loads to drink and then go to bed together, but alas, only a dream.’ (Quoted in Richard Bradford’s The Importance of Elsewhere: Philip Larkin’s Photographs.)

It is tempting to see in Amis’ use of Larkin an attempt to expose who Amis himself really is. Amis’ favourite iteration of Larkin is as the poet in Oxford in the early 1940s, when Larkin was ‘a flashy dresser and a charismatic talent who for a while felt socially bold’. Amis goes on to excoriate the ‘old buzzard’ Larkin for the continual disaster of his personal life, and his forever standing outside ‘the flow… the tide’ of life. For Amis, Larkin’s ultimate personal failure is quite simply his failure to marry and have children. In conversation with Hitchens, Amis approvingly quotes his mother Hilly’s belief that ‘childlessness dooms you to childishness’.

Thus Amis’ depiction of Larkin does raise questions, if not answers, about what Amis sees as the perennial problem of finding ‘a decent deal between men and women’, as he put it when his novel The Pregnant Widow came out in 2009. If Phelps represents Amis’ deeper meditation on the poisoned chalice of the sexual revolution for women, then Larkin may represent the danger of perpetual childishness for commitment-averse men.

As Amis and his fellow British bratpackers Julian Barnes, Ian McEwan and Salman Rushdie approach the beginning of the end of what Amis calls ‘Act V’ of their lives, it might be worth pondering if Inside Story represents some sort of swansong. Indeed, it will be interesting to see if Amis himself returns to a more conventional form for any future novels he may write.

Poignantly, it is the death of Hitchens, the one who got away, that provides the final and greatest lesson of this book — namely, how to die well. ‘How young and handsome he was’, writes Amis. ‘How calmingly young and handsome. He looked like a thinker, a hard thinker, taking a brief rest… Now reason slept, now the sleep of reason; he looked like Keats on his white bedding in Rome; he looked twenty-five.’ A life, like Amis’ own, to be remembered not at its end, but at its height.

Neil McCarthy is a teacher and writer based in Dublin.

Inside Story, by Martin Amis, is published by Jonthan Cape. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.