We should never have closed schools

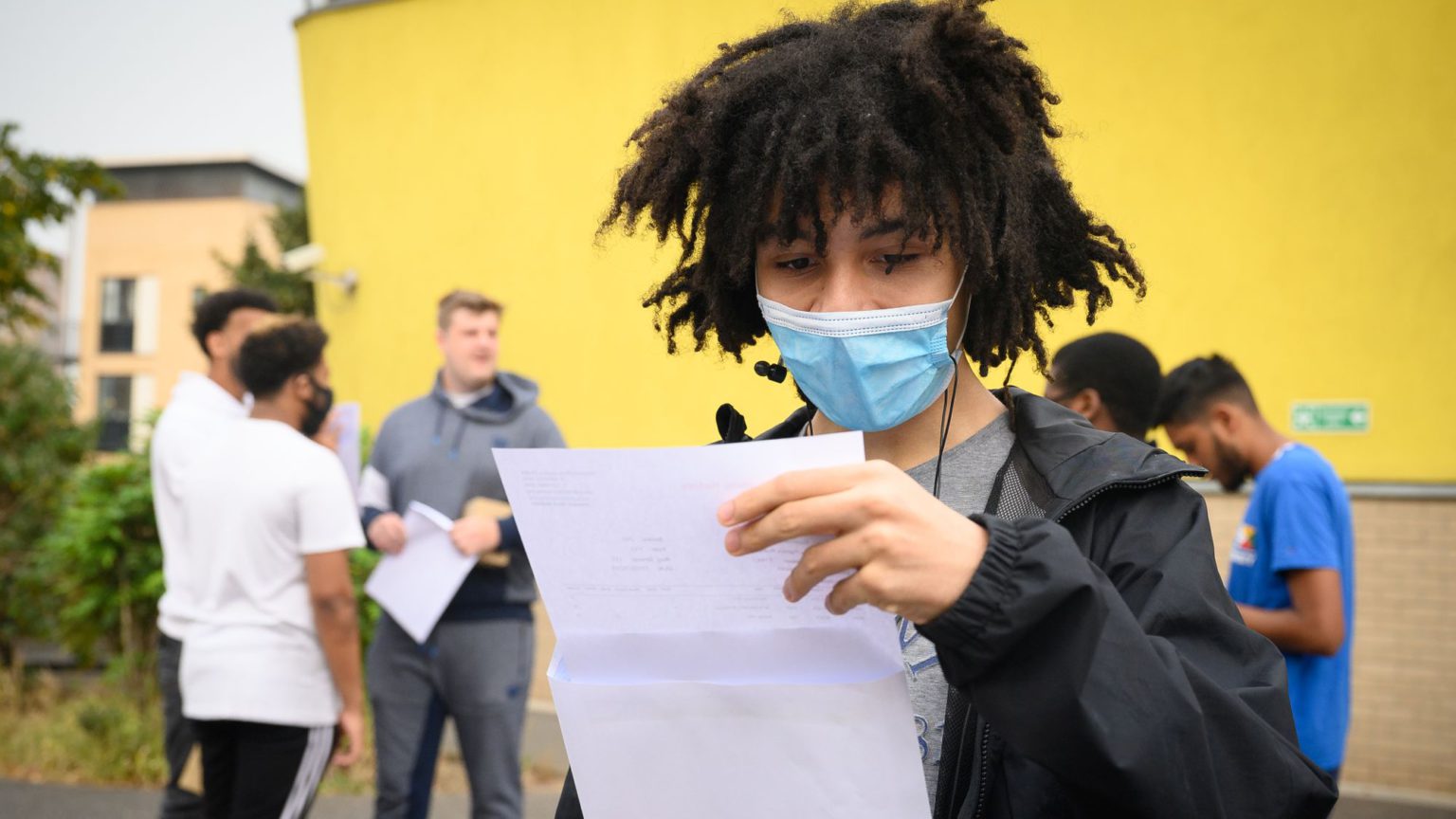

Young people will bear the brunt of our panicked response to the virus.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The A-level by algorithm scandal rolls on, lurching from crisis to chaos. Government messaging shifts randomly between an insistence that nothing will change and suggesting that if students are disappointed with their allotted grades, they can simply pick others. Just this weekend, reassurances about appealing lower-than-expected results were swiftly followed by Ofqual (the exams regulator) removing from its website all details of how the appeals process would work.

The devastating impact this has on the lives of all involved cannot be overstated. A cohort of 18-year-olds have missed the end of their school days with all the associated rites of passage, had summer holidays and festivals cancelled, and have been unable to get jobs in bars or restaurants, only to see their exam results turned into a political football. Some have lost university places and are now having to drastically rethink their future plans.

What has gone so badly wrong? Amid all the noise it’s easy to miss the fact that, across the board, A-level grades are actually up on previous years. The proportion of entries graded at A or above has increased to 27.6 per cent from 25.2 per cent last year. Results were deliberately kept in line with past performance in order to avoid grade inflation and, importantly, devaluing this year’s marks.

Even though results are up overall, almost 40 per cent of grades awarded fell below those predicted by teachers. If teacher assessments stand unmoderated, there will be a large increase in the proportion of students getting top marks. Ofqual has been critical of schools making ‘implausibly high judgements’. There are many reasons why teachers might be generous in making predictions. Exam results are used to judge the performance of both schools and individual teachers. Perhaps more significantly, teachers want what’s best for their pupils and exam success is seen as key to university, future employment prospects and self-esteem. Ofqual’s algorithm was designed to compensate for teacher generosity and to keep each school’s performance in line with previous years.

The problems this creates were surely predictable. The algorithm cannot discern whether a teacher is being generous to the bright students at schools that perform poorly or to the lazy students who attend high-performing schools. Instead, it bakes in pre-existing differences and then further exacerbates inequality by excluding schools with only a small cohort of A-level pupils from the algorithm’s workings. In such cases, generous teacher-assessed grades stand unmoderated. The upshot is that pupils at smaller schools – which are more likely to be fee-paying – have, in general, received the grades the teachers predicted for them while students at large sixth forms, particularly those in more disadvantaged areas, have been awarded lower grades.

The Department for Education and Ofqual are now, rightly, facing a barrage of criticism for their handling of this situation. Angry students and parents are demanding the national algorithm be corrected and reapplied. But no algorithm, no matter how sophisticated or how rigorously applied, could ever provide a fair measure of individual performance in the same way as an exam. The fact that all students sit the same exam, at the same time, under the same conditions, acts as a great leveller. It provides an opportunity for determined youngsters to prove their capabilities no matter what their postcode or which school they attended. Scrapping exams – and not the application of a dodgy algorithm – has denied an entire cohort this opportunity.

Cancelling exams was rarely questioned back in March when schools were closed. It was seen as inevitable – and perhaps for good reason. Over the past five months huge educational inequalities have been exposed. Whereas some, mainly private-school pupils, have received a full timetable of online lessons, others have barely received an emailed worksheet to complete. It would hardly have been fair to pitch pupils who had been taught up to the last minute against those who had gone for three months without any contact with a teacher, no wifi and not even an open library. Although, as we are now discovering, perhaps this would still have been more equitable than an algorithm.

Closing schools has led directly to the current results fiasco. But it is the very same people who demanded school closures back in March, and who had an almighty strop every time the prospect of reopening schools was mooted, who are now complaining most loudly about inequality and injustice. They let a cohort of youngsters down and now they have the cheek to complain. It truly beggars belief.

Schools were shut so casually because education carries so little value today. To government ministers, grades are simply about opening doors to university and employment. To some teaching-union leaders and commentators, exams are stressful, unfair and should be scrapped altogether. Almost no one argues that exam results provide a measure of what students know about a subject and that this is important in its own terms.

There is nothing inevitable about the current exam chaos. We could, right now, have a fair appeals system up and running. Results could have been released to schools at the beginning of this month, in time for teachers to flag up errors and appeal on behalf of individual pupils. Alternative forms of assessment could have replaced exams. Schools could have remained open to students in their final year of GCSE or A-levels. But all of these solutions would require valuing education and seeing 18-year-olds not as numbers on a spreadsheet or as vulnerable creatures to be flattered and appeased, but as capable and resilient young adults.

As we head into next academic year amid continued panic about schools and coronavirus, two things are clear: exams are the fairest method we have of assessing individual merit and we must do everything possible to keep schools open. Let’s hope students are not the only ones capable of learning lessons.

Joanna Williams is director of the Freedom, Democracy and Victimhood Project at Civitas. Covid Kids: The response of schools to coronavirus is free to download.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.