The Mis-anthropocene

Calls for a ‘no growth’ future reveal the limits and misanthropy of today’s radicals.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The coronavirus pandemic has done terrible damage to Britain. The estimates of those who have died with the disease are, at the time of writing, just over 34,000. On top of the misery of lost friends and loved ones, the knock-on effects on people’s lives, their jobs and hopes are terrible. The government and the NHS have rightly come under sharp criticism for their handling of the crisis.

In his address to the nation, the opposition leader Keir Starmer said he wanted to support the government in its fight against the coronavirus, but we ‘can’t return to the old ways’. Starmer argues that the country needs to better reward health and other key workers and to better fund the healthcare system and the care sector. This has chimed with a lot of people’s thinking. Indeed, the Conservative Party’s election manifesto already promised a £34 billion increase in health spending by 2023. In mid-April, chancellor Rishi Sunak brought forward £6 billion of health spending specifically to fight the coronavirus.

But there have been more forthright criticisms not just of the Conservative government but of capitalism more generally, and, in particular, of the ‘growth model’ of the economy. To some critics, the epidemic itself is symptomatic of a more fundamental crisis of modern society – and also an opportunity to systematically transform the country and the world. These critics mix anger at the death toll with a determination to use the crisis to forward a new agenda.

‘Revolutionary times need revolutionary measures’, left activist Owen Jones told a Novara Media webcast. He summoned the historical comparison of Keir Starmer as Clement Attlee to Boris Johnson’s would-be Winston Churchill, recalling that Attlee won the postwar election to build the welfare state.

Writing in the Guardian, Adam Tooze puts the epidemic in an even more momentous time-frame, arguing that we are in the first ‘crisis of the Anthropocene’. ‘This is the era in which humanity’s impact on nature has begun to blow back on us in unpredictable and disastrous ways’, he says. Veteran labour analyst Kim Moody argues that ‘capitalism has accelerated the transmission of diseases’ and that ‘this virus has moved through the circuits of capital and the humans that labour in them’.

‘To protect human wellbeing and avoid environmental disaster, we must escape the growth paradigm once and for all’, write David Barmes and Fran Boait in a report called The Tragedy of Growth. The report has been backed by Green MP Caroline Lucas and Labour’s Clive Lewis. Among its proposals is a Universal Basic Income. Its main contention is that ‘the climate and ecological emergencies necessitate that we end our pursuit of GDP growth’.

What a shame there aren’t any more ambitious ideas about how to change society. The flaw in the arguments about ‘we can’t go back to the old ways’ is two-fold. The first is that too many of the ideas for change are wrong and destructive, and if put into practice would sabotage our ability to recover. The second is that they are intuitive appeals to a common ground that has not yet been argued for.

The case that the growth of mass societies across the globe has created a vector for viral infection is undeniable. No other species than man is as mobile or as ubiquitous across the globe. It is clear, too, that globalisation really comes when people give up subsistence farming to work for wages, which is to say, under capitalism.

Scientists in the Soviet Union first mooted the idea that we were in a new age, the ‘anthropocene’, in which human intervention in nature was the defining characteristic of the age. The claim is that the Anthropocene is analogous to the Holocene (the time since the last Ice Age), the Pleistocene (the Ice Age itself) or the Eocene (up to the great extinction 34million years ago). Except, of course, the defining characteristic of the Anthropocene is human intervention, rather than natural or climatic changes. Whether this really is a new age, Adam Tooze and other theorists of the Anthropocene are right to say that the deeper engagement with nature that modern industry and agriculture creates also opens up a greater possibility of cross-species viral infection, which would appear to be the source of human Covid-19.

But where the Jeremiahs of the Anthropocene get things wrong is in their argument that a deeper relationship with nature is harming humanity more broadly. While it is true that modern industry and agriculture have increased the vectors of viral infection, they have also hugely increased our ability to cope with diseases and other natural impacts on human society.

Historically, influenza epidemics spreading from developed Western societies to those in the Pacific and the Americas, which were only just beginning to open up to modern commercial society, were devastating. The 16th-century smallpox epidemic, in what is today Mexico, wiped out nearly 20million – reducing the population to one tenth of its previous size. Measles killed vast swathes through the Melanesian Pacific in the 19th century.

Today smallpox is no longer with us, having been finally eradicated by vaccination in 1980. Measles, though a significant killer still – and in resurgence in 2018 – can be controlled by vaccination. Influenza killed as many as 50million in the 1919 Spanish Flu pandemic, putting even coronavirus into the shade. Overall, modern medicine has significantly improved life chances across the globe.

And it is not just medicine that improves lives. Industry generally has had a dramatic impact upon the longevity and the quality of human life. It turns out that a deeper and more extensive interaction with nature actually protects us against natural disaster. Far from being more precarious, life in this age is more secure and richer than it has ever been.

The Tragedy of Growth report dismisses the importance of industrial growth for increased life expectancy, claiming instead that industry is bad for us. But since the Industrial Revolution, British life expectancy has doubled from an average of 41 years in 1841 to 81 years in 2018. People’s lives have gained an extra decade since 1960. Even the terrible losses of coronavirus will not leave Britain’s population smaller in 2021 than in 2019, given the average natural population growth of around 200,000.

It is curious that in their preoccupation with the negative impacts of human intervention in nature, the critics of growth and humanity fail to register the positive impact that human intervention has in making nature more amenable to human needs.

The Anthropocene, as the argument goes, would run from the agricultural revolution 12,000 years ago, or perhaps from the Industrial Revolution 250 years ago. But perhaps what we are really looking at is the emergence of the misanthropocene – an era marked by pessimism about man’s future. Such misanthropy has taken hold over the past 30 years, with the growth of green parties across the world, the declaration of the ‘End of History’ and other postmodern philosophies. The underlying argument of the misanthropocene diminishes human achievements and enjoins us to bow down before nature – including the mighty coronavirus.

In the misanthropocene, the difference between a left-wing, radical critique of the social order and the environmental critique of growth has collapsed. It is interesting that today Adam Tooze looks back on the publication of the The Limits to Growth as a seminal moment. The report was produced in 1972 by the Club of Rome, a think-tank founded by a wealthy industrialist. In it, we were warned about the ‘natural forces that could interrupt the triumphant path of economic growth’.

When The Limits to Growth was first published, it was attacked by leftists who argued that it displaced social critique for Malthusian Jeremiads about overpopulation. Radicals of that era insisted that growth was the key to overcoming scarcity. But today, Labour’s Clive Lewis and the Greens’ Caroline Lucas are jointly launching a ‘no growth’ economic plan.

The proposition that we should aspire to a ‘no growth’ economy cannot be squared with the commitments to increase spending on the health service or to continue paying 80 per cent of workers’ wages while they are furloughed at home.

This problem has been waved aside by some radical economists who say that there is no limit on the amount of cash that the Bank of England can print. Economists like Mariana Mazzucato and James Meadway argue that the additional costs of the coronavirus do not have to be paid back, and that the government ought to go on spending to avoid a crisis. The school of Modern Monetary Theory goes even further, arguing that there are no limits at all to governments printing money to pay for welfare services.

The radical economists are not wrong to say that it would be a big mistake to try to reduce the deficit by austerity measures. On the other hand, printing money cannot be a substitute for real economic activity. The furlough scheme and other rescue packages can put off our economic problems but cannot solve them. If the money the government issues does not correspond to real goods and services, it will not magically bring those things into being. As the bottleneck shortage of personal protective equipment has shown us, goods have to be made before they can be bought and used.

We are only able to fund the health service now because the government can borrow money on the expectation that the economy will return to productive growth. Those who imagine that the ‘money printer go BRRR’ and everything will be solved are deluding themselves. (If governments really could just print money to pay for welfare services in perpetuity, they could stop taxing businesses altogether. But one suspects that is not a conclusion that Modern Monetary Theorists would support.)

Similarly, the appeal of the proposal for Universal Basic Income, to be paid to each of us regardless of any work we do, is that it creates an imaginary release from the necessity of making a living. The hope that a wise and beneficent government might pay us all to stay at home does not seem so strange when that is what is happening right now. But as Karl Marx pointed out, even a ‘child knows that any nation that stopped working, not for a year, but let us say, just for a few weeks, would perish’. That is not just true of capitalism, but of all societies, even socialist ones.

It is a feature of the lockdown that the political process has been largely suspended. A lot of people are daydreaming about the future without really testing those ideas in public debate. ‘We can’t go back to the old ways’ seems intuitively true. Say it and people will nod sagely as if in agreement with you.

In the closing scene of Tim Burton’s Mars Attacks, standing on the shattered steps of the White House after the alien invasion has been fortuitously defeated, accidental saviour Richie Norris says, ‘We will rebuild’. He then adds: ‘But instead of houses, we could live in teepees, which are much better in a lot of ways.’ Burton’s joke is that mankind has only saved itself by accident and has not actually worked out how things could be any better. After the denouement of the world’s near destruction, living in teepees seems as good an idea as any.

Many people have looked at the unpolluted skies or walked the empty streets and thought ‘We can’t go back to how it was’. But tunnel down further into those sentiments, and you will find that they mask clashing ideas of how things ought to be. Though people are happy to come out and clap for the NHS, that does not mean they are in agreement about how to fund it. The coronavirus epidemic has indeed been momentous, but it will not resolve the arguments about how we should go forward.

The measures that the government has taken to stabilise the economy under the lockdown are indeed revolutionary, but they have only been taken in order to sustain the capitalist system. Far from being a moment of great social solidarity, the lockdown is one of enforced isolation and atomisation. So far, the epidemic has only enhanced the Conservative government’s position in the opinion polls.

No doubt there are many people who see the epidemic as evidence that the modern world has gone wrong. Maybe there are even some who think that growth ought to be done away with altogether. But a great many more think that the economy must eventually get back into gear to make good the losses caused by the epidemic and the lockdown. Some people who say they do not want to go back to the old ways want to pull up the drawbridge and isolate the country from overseas dangers. Others want to see more cooperation with allies and partners around the world to meet the new challenges.

Without a political process to test out the different proposals of how the country ought to change, the sentiment will only tend to mask the debate. The proposal of a post-growth future is no more realistic than the idea that we should all live in teepees.

James Heartfield is author of The Equal Opportunities Revolution, published by Repeater.

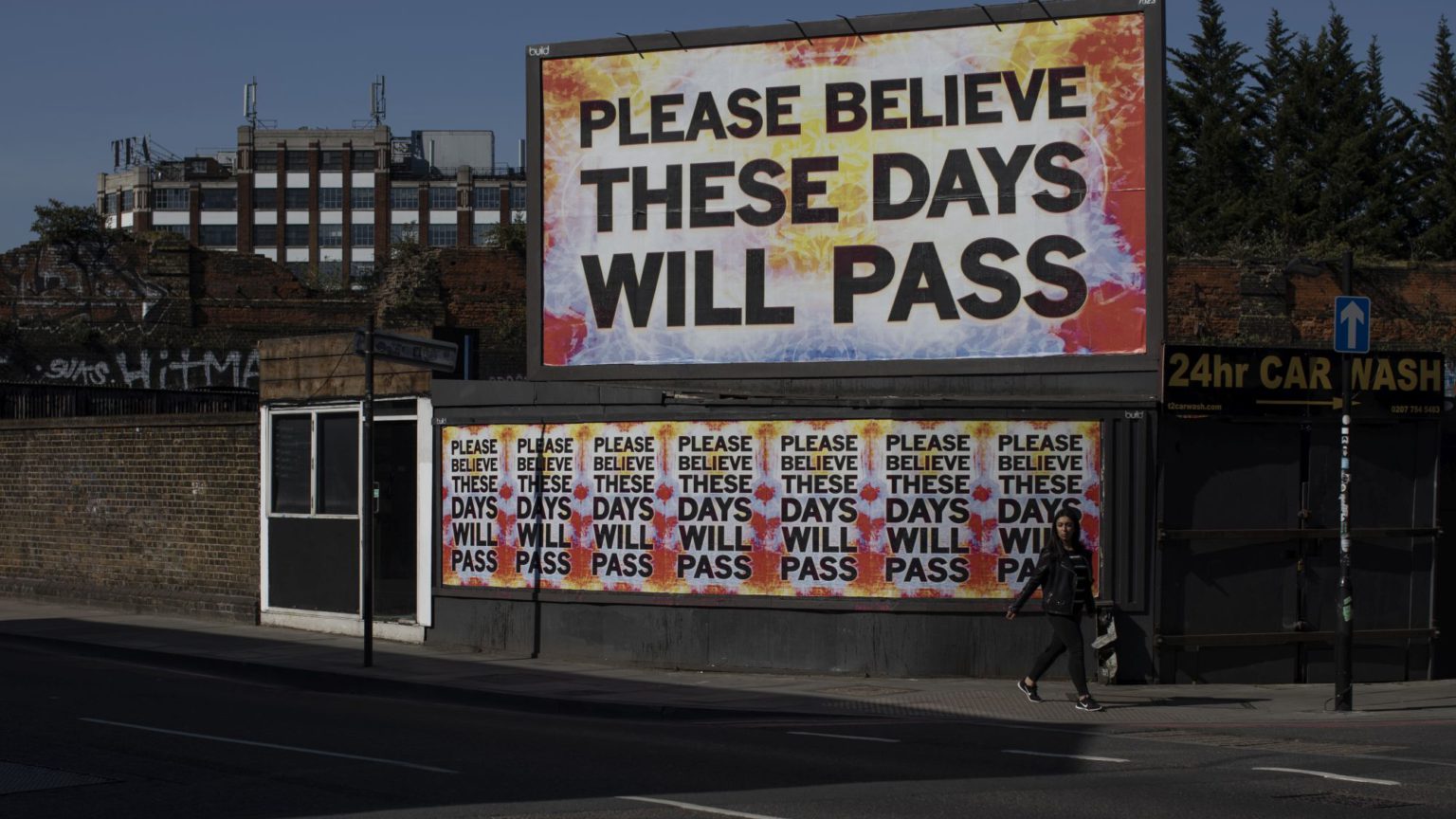

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.