Long-read

The making of a global pandemic

How the Spanish Flu was turned into an anticipation of the apocalypse.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Some are now convinced that the Spanish Flu may have started in the Chinese province of Shanxi in the winter of 1917. Others contend that it originated in the cramped environs of a British army camp at the fishing port of Etaples, just south of Boulogne-sur-Mer, in December 1916. And some claim that its first victim was a poor agricultural labourer in Haskell, Kansas, in January 1918.

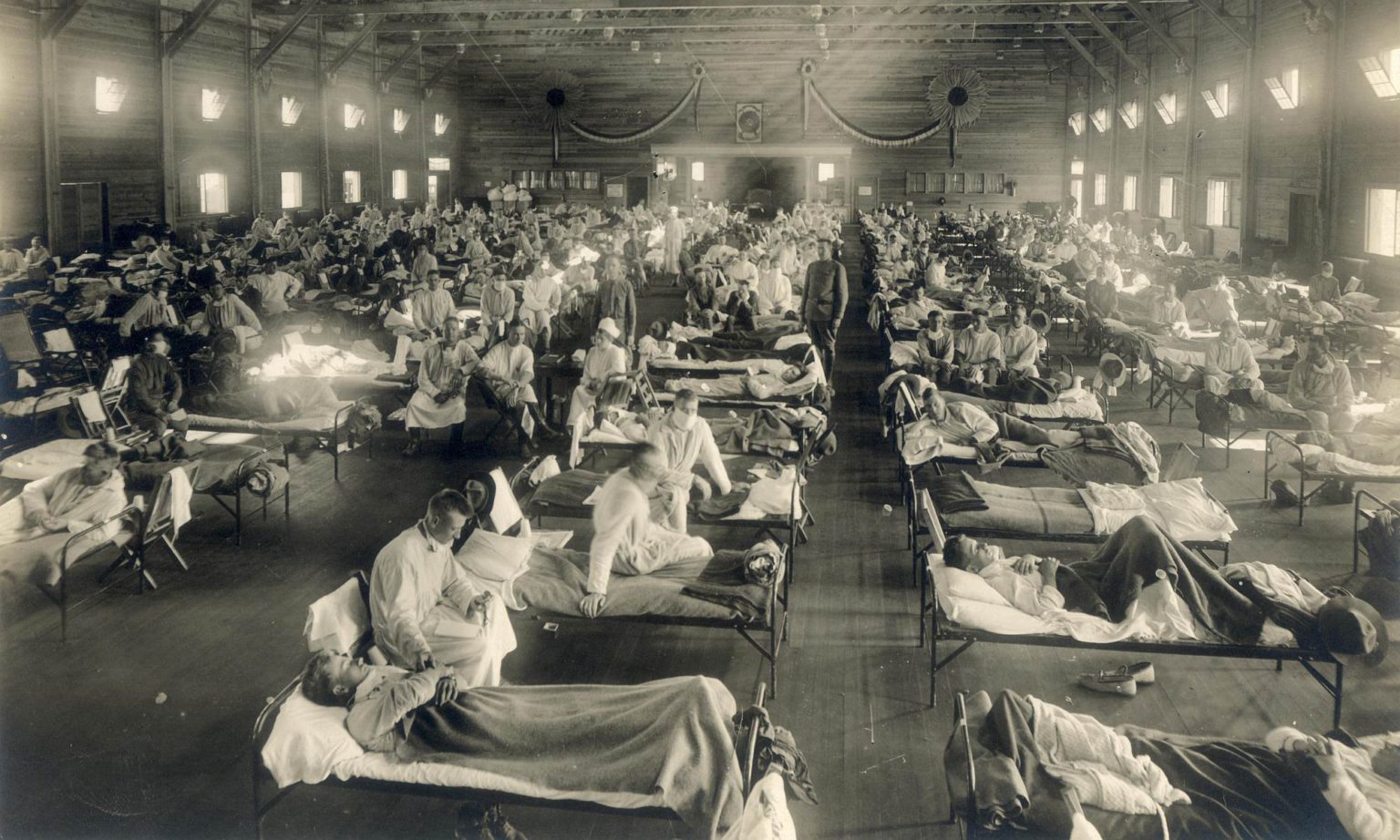

So much for the speculation. It remains widely accepted that the first official patient was a US conscript by the name of Albert Gitchell, who, on 4 March 1918, reported to doctors at Camp Funston in Kansas, with a fever, headache and sore throat. ‘By lunchtime’, writes Laura Spinney in her 2018 history of the Spanish Flu, Pale Rider, ‘the infirmary was dealing with more than a hundred similar cases, and in the weeks that followed so many reported sick that the camp’s chief medical officer requisitioned a hangar to accommodate them all’.

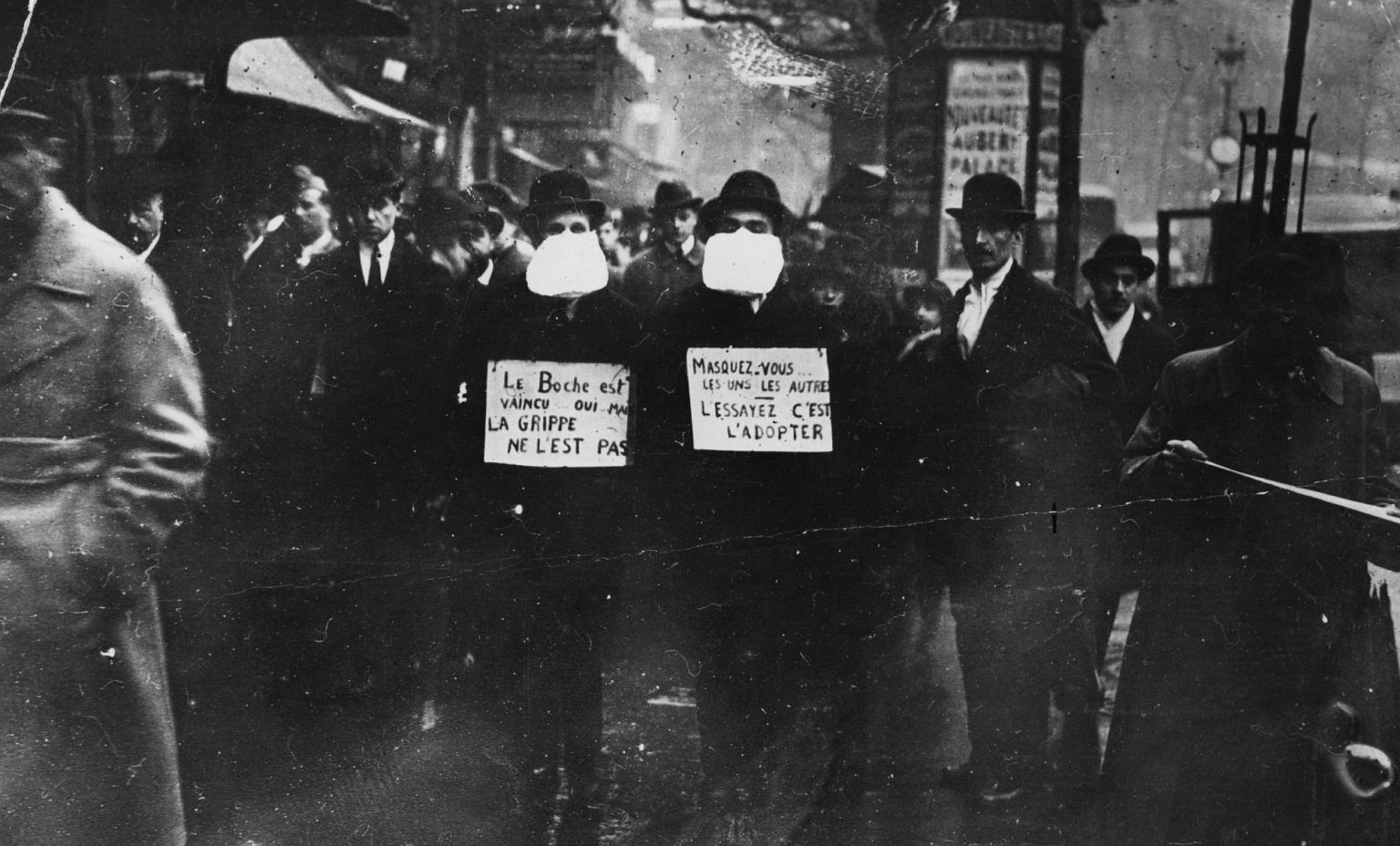

By the beginning of April 1918, the mysterious illness was making people sick in the American midwest. By the middle of April, it had accompanied US troops to the trenches on the Western Front. And from there it spread to the whole of France, before being carried to Britain, Italy and war-neutral Spain, where, thanks to the absence of reporting restrictions, the Spanish Flu literally made its name.

Medics in the European theatre of war could see the effects of the flu were causing chaos, as it passed silently through the mass movements of troops. They were well aware something was gravely amiss, not least because, unlike other flu outbreaks, it was severely affecting and killing men in their 20s to 40s, rather than just the very old and very young. But they did not know what it was. A medical officer at a US army hospital in Bordeaux described it as an ‘epidemic of acute infectious fever, nature unknown’. Others identified it merely as ‘grippe’.

In May, it reached North Africa, then India and China, where it was eventually to kill tens of millions, before seemingly petering out in America and Europe. This, as it turned out, was merely the relatively mild first wave.

In August 1918, the second wave struck three points around the Atlantic – Freetown in Sierra Leone, Brest in France and Boston in America – incubated and transported, no doubt, by returning troops. At Camp Devens, 30-or-so miles to the east of Boston, it soon became clear that this wave of Spanish Flu was lethal.

William Henry Welch, the foremost pathologist and physician in the US at the time, had been dispatched to Devens to investigate an outbreak of illness deemed too severe to be flu, involving fever, meningitis and ‘pneumonic complications’. When he arrived on 23 September, he was told there were 12,604 active cases, and that 66 physically fit young men had already died. As the historian Alfred Crosby records, the morgue was chaotic, with bodies ‘stacked like cordwood’. The post-mortems told Welch little beyond the cause of death – lungs filled with a thin, frothy, bloody fluid. But they were enough to terrify even the war-weary Welch, who was moved to describe the illness as ‘a plague’ (1).

Indeed, the physical effects of the second wave are the source of much of the horror now associated with the Spanish Flu. The lips, cheeks and extremities of those whose lungs had been compromised by pneumonia would turn blue, lavender and then almost black, as they began to drown in their own fluids. Many would haemorrhage blood, expelling it out of their mouths and nostrils. And the end was mercifully quick, too. Some people were reported to have fallen dead where they stood.

So, while military conflict was drawing to a close in the autumn of 1918, this mutation of the Spanish Flu was quietly wreaking devastation on an even greater scale than the war itself. By March 1920, when the third, very mild wave had made Spanish Flu’s final pass, Mark Honigsbaum estimates that 675,000 Americans, 400,000 French and 228, 000 British had lost their lives to it (2). ‘Worldwide, the death toll from the Spanish flu pandemic has been estimated at 50million’, continues Honigsbaum, ‘five times as many as died in the fighting in the First World War and 10million more than AIDS has killed in 30 years’. Some put the death toll even higher, at 100million, which amounts to five per cent of the world’s then population. As Spinney concludes, ‘It was the greatest tidal wave of death since the Black Death, perhaps in the whole of human history’.

The insignificant pandemic

And this is what is so perplexing about the Spanish Flu: ‘The most deadly disease event in the history of humanity’, as the World Health Organisation was later to call it, had virtually no cultural, political impact in Europe or America. It happened, but it was not marked. Not dwelled upon. Not memorialised.

The sheer overwhelming import of the Great War itself, the conquest and collapse of Empires, and the revolutionary upheaval in Russia, may partially explain the flu’s public eclipse. If there was a narrative to be told, it involved armies and political struggle, not microbes and infection rates.

Besides, life was much more brutal, nasty and short 100 years ago. The average European or American could expect to die in their fifties, and someone from India, where the Spanish Flu is estimated to have killed between 12million and 17million people, might struggle to reach their thirties. Severe disease, epidemic and endemic, was commonplace. And the flu, Spanish or not, was positively vulgar, even a subject of grim mirth for the war poets Wilfred Owen and Robert Graves, who mocked the mundanity of its threat. ‘STAND BACK FROM THE PAGE! and disinfect yourself’, wrote Owen to his mother of a flu outbreak at his camp. Indeed, it was Typhus, an often fatal blood-borne disease carried by lice, that was the blight of the frontline, not the flu.

Medical complacency may also have blunted people’s sense of the flu’s import. This was because the persistent ubiquity of killer diseases coexisted with a high degree of medical confidence that their cures were soon to be found, thanks in large part to the huge advances in bacteriology and germ theory made by Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch and their colleagues in the second half of the 19th century. This confidence may have been misplaced (the medical establishment was labouring under a misapprehension, not corrected until the 1930s, that flu was a bacterial infection, rather than a viral one). But it did mean that many infectious diseases had been thoroughly demystified and defanged. They increasingly manifested themselves as technical health problems to be managed, rather than portents of doom, or symbols of religious punishment.

But there is a more important reason why the Spanish Flu was seemingly incapable of leaving a cultural, political mark: the fact that it signified nothing beyond itself. People had no need of it either as a figure, or as a metaphor. It therefore never played a broader role in public and cultural life because it meant so little.

This is clear not just from the fact, as Spinney puts it, that there is no cenotaph, no monument in London, Moscow or Washington DC for the Spanish Flu. It is also clear from the fact that it is largely absent from the cultural production of the 1920s more generally. The war features, of course, as metaphor as much as grim, bloody reality. And more pertinently, so does physical and mental illness, be it tuberculosis or shellshock, both of which remained rich in figurative meaning throughout the 1920s. But the ‘most deadly disease event in the history of humanity’, barely warrants a mention.

The Spanish Flu was absent from public and cultural life because it meant so little

It was surely not for want of awareness of the magnitude and threat of Spanish Flu, despite the distractions, deprivations and press restrictions of wartime. As Elizabeth Outka notes of Britain in Viral Modernism, ‘Newspapers in England reported on the high numbers of people who collapsed in the street; in October 1918, for example, The Times noted that people were “suddenly affected by the disease in the streets,” and by early November, in one 24-hour period alone, “56 people were stricken with sudden illness in the London streets,” with 280 similar cases that week’.

Likewise, the Spanish Flu was hardly played down by the British state. Then chief medical officer George Newman wrote in his 1920 public report on the flu that it was ‘one of the great historic scourges of our time, a pestilence which affected the wellbeing of millions of men and women and destroyed more human lives in a few months than did the European war in five years’. Elsewhere, a Times editorial from December 1918 even anticipated the judgement of a hundred years hence: ‘Never since the Black Death has such a plague swept over the face of the world.’

Nor was the flu’s absence from public works and discourse for want of politicians’, writers’ and artists’ firsthand experience of it. Many significant cultural and political figures became infected. Franz Kafka was laid up with it as the Austro-Hungarian empire collapsed outside his window; TS Eliot caught it as London celebrated the armistice; and British prime minister David Lloyd George nearly died from it as the Allies moved towards victory. Others were lost to it, too. Guillaume Apollinaire, poet and literary forerunner of the 20th-century European avant-gardes, perished aged 38, as France welcomed the peace. And the great social theorist Max Weber caught the flu’s milder tailend in early 1920, before dying aged 56.

And yet for all the widely acknowledged death and loss the Spanish Flu caused, it refused to mean much more beyond these millions of brute, private tragedies. It neither bled into the metaphorical sphere, nor did it refer to something beyond itself. Which was unusual. Leprosy, for instance, had at one point literally embodied moral corruption. And the bubonic plague had long signified supernatural punishment. But there was no cultural and political desire to transfigure the Spanish Flu as something it was not. It was divested of symbolic or emblematic potential. Indeed, it remained steadfastly itself – a disease.

Not all agree. There are attempts today to see in, say, flu-sufferer Edvard Munch’s 1919 self-portraits, with him sat, sallow and gaunt, in a wicker chair, the melancholia of his post-flu vision. But such melancholia was entirely typical of Munch’s pre-flu vision, too. Likewise, some have attempted to divine the presence of WB Yeats’ dalliance with the flu in the apocalyptic mythos of ‘The Second Coming’, in which ‘Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; / Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, / The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere / The ceremony of innocence is drowned.’ Yet this sense of chaos and the rising meaninglessness of a godforsaken existence, and the attempt to forge meaning through artistic form, was characteristic of modernist culture in general, from the mid-19th century onwards. The war certainly exacerbated and confirmed such a sense, but the flu didn’t. As Virginia Woolf remarked in On Being Ill (1926), illness simply did not work as a literary theme: ‘[There are] no epic poems to typhoid, odes to pneumonia, lyrics to toothache…. More practically speaking, the public would say that a novel devoted to influenza lacked plot.’

This is not to say that the Spanish Flu was completely unrepresented. In the US in particular, the outbreak provided the background to Willa Cather’s One of Ours (1922), Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel (1929), and William Maxwell’s They Came Like Swallows (1937). But even in its most famous artistic rendition, Katherine Anne Porter’s part-modernist short story Pale Horse, Pale Rider (1939), its role is not as central as it seems.

Porter, who nearly died from the Spanish Flu herself, tells the story of a young woman called Miranda, who is in love with Adam, a young conscript about to be sent to war. She is haunted throughout not so much by the flu (the symptoms and manifestations of which creep up on the reader) as by the spectre of death itself, represented by the pale rider who appears to her in a dream sequence at the novel’s beginning. An ending – the ending – therefore prefigures the novel’s narrative. Every event and thought subsequently narrated is thus read in the light of immanent death.

‘This is the beginning of the end of something’, Miranda says to herself. ‘Something terrible is going to happen to me.’ Quite so, although it is far worse than she can imagine. For Miranda survives the flu, dragged through it by ‘a minute fiercely burning particle of being that knew itself alone, that relied upon nothing beyond itself for its strength; not susceptible to any appeal or inducement, being itself composed entirely of one single motive, the stubborn will to live’. Yet while she lives, her reason for living – Adam – does not. And just to add an extra layer of irony, he dies, not in ‘the war, the WAR to end WAR, war for Democracy, for humanity, a safe world forever and ever’ – which is mocked mirthlessly throughout – but from the flu, having contracted it from Miranda.

So, Miranda is alive at the end, but, from her perspective, life is now dead: ‘She saw with a new anguish the dull world to which she was condemned, where the light seemed filmed over with cobwebs, all the bright surfaces corroded, the sharp planes melted and formless, all objects and beings meaningless, ah, dead and withered things that believed themselves alive!’ The final lines of Pale Horse, Pale Rider still resonate:

‘No more war, no more plague, only the dazed silence that follows the ceasing of the heavy guns; noiseless houses with the shades drawn, empty streets, the dead cold light of tomorrow. Now there would be time for everything.’

These are the true themes of Pale Horse, Pale Rider: not just the absurdity of a life lived in the shadow of death; but also the absurdity of life after the death of everything that gave life meaning. The final line – ‘Now there would be time for everything’ – is beautifully, ambiguously poised between promise and punishment.

The Spanish Flu is of course central to Porter’s narrative, just as the war is. But it is not laden with especial significance. Rather, it is treated literally – as a disease from which many were dying – just as the war is treated literally – as a conflict in which many were dying. Its function, as a source of cruel meaningless death, is to act as an ironic counterpoint to the war, a source of supposedly meaningful, patriotic death, talked up by ‘potbellied baldheads, too fat, too old, too cowardly, to go to war themselves’. For Porter, then, the flu exposes the truth of the war: it is for nothing.

So even in the novella most cited by those looking for the Spanish Flu’s presence in Western interwar culture, the flu’s importance lies in its sheer meaninglessness. It is a source of death. And nothing more.

The inability of the flu to signify something beyond itself really is striking. Throughout the culture of the interwar period, there were anxieties and fears aplenty, of course. But they were just not being projected on to the flu. It was a disease muted by the lack of cultural or political investment in it.

The remembered pandemic

This is not to say that a veil of silence was drawn over Spanish Flu. Rather, it is to say that from the 1920s until the 1970s, the Spanish Flu had no other meaning than as an infectious disease. It was framed almost entirely in terms of a public-health problem, an object of study for bacteriologists and epidemiologists; an object for people like Edwin Jordan, who conducted several international studies of the pandemic for the American Medical Association, and, in 1927, was the first to estimate a death toll, which he put at 21.6million; or an object for those who authored the British Ministry of Health’s account of the pandemic in 1920, and stated that their ‘historical survey will prove invaluable for future reference in the event of subsequent epidemics’.

But beyond the medical profession and public-health bodies, the Spanish Flu remained utterly insignificant for much of the 20th century. In the ‘Casualties and War Statistics’ volume of Britain’s official History of the Great War Based on Official Documents, published in 1931, the authors blithely declare: ‘Apart from reproducing… the recorded figures for influenza in the British armies at home and abroad during the Great War little need be said about this disease.’ And little was said. For historians, politicians, writers, philosophers – indeed, anyone not working in medicine – the Spanish Flu pandemic appeared largely meaningless. Even relatively recent histories of the 20th century, such as Eric Hobsbawm’s Age of Extremes (1994), omit to mention ‘the greatest tidal wave of death in the whole of human history’ – not even in a footnote.

In the 1960s and 70s, however, interest in the Spanish Flu stirs. Historian Adolph A Hoehling’s The Great Epidemic, appeared in 1961. Charles Graves’ Invasion by Virus: Can It Happen Again? followed in 1969. And, most notably, Richard Collier’s The Plague of the Spanish Lady, which solicited and featured the personal accounts of over 1,700 survivors, arrived in 1974.

At this point, the Spanish Flu was still a minority interest. But the sensationalist tone of these books, their focus on the horror and panic provoked by a pandemic, and the titillating ‘can it happen again?’ speculation, indicated that this once insignificant pandemic was starting to acquire a meaning beyond itself. That is, it was starting to be used metaphorically, as a means to express contemporary anxieties, in this case about the threat of mass death and foreign, no doubt, Communist threats (hence the virus ‘invades’, just as the equally Communist-inspired alien body-snatchers did in the 1956 film).

This meaning did not occur in the original influenza outbreak. Rather, it was being created in the interaction between the concerns, anxieties and interests of the then present and the material of the past. For this was a moment in the West in which the imagination of disaster, as Susan Sontag put it in 1965, was flourishing. A moment in which the Bomb loomed large in the minds of many, the Reds were becoming ever more menacing, and the Holocaust continued to cast its shadow. A moment in which individuals, increasingly deprived of forms of collective agency and the hope of a remedial politics, felt subjectively more and more impotent.

There were objective prompts for the growing subjective sense of hopelessness and powerlessness in the West – the persistence of the Cold War, the end of the postwar boom, and the US’s effective defeat in Vietnam, for instance. But the subjective response was crucial. Many seemed demoralised and atomised, preferring to hunker down, and just try to get by. Hence it was at this very point that what Christopher Lasch, in 1984’s The Minimal Self, was to call the culture of survivalism became ever more prominent. Individuals, he wrote, were treating everyday life as a series of potential threats, a struggle, something they had to protect themselves from, as a means to preserve their minimal sense of selfhood. Not because they really were more at risk, but because they felt increasingly vulnerable. Is it any wonder that it is at this very moment, when a sense of combined individual vulnerability and impotence is growing, that the Spanish Flu starts to acquire an extra-medical significance? Moreover, the Asian Flu epidemic of 1957, and the Hong Kong Flu epidemic in 1969, which together killed around three million people worldwide, reminded the public of the Spanish Flu. It was therefore ripe for metaphor – ripe to become ‘a harbinger of agentless chaos, a reminder that one’s vulnerability can lie outside all control’ (3).

From the 1920s until the 1960s, the Spanish Flu had no other meaning than as an infectious disease

During the 1980s and especially the 1990s, as the post-Cold War West became ever more disoriented, the AIDS pandemic emerged, and ecological collapse seemingly accelerated, this cultural sense of vulnerability was becoming ever more pronounced. It didn’t matter that our collective, technological power over the physical environment was increasing. This just seemingly deepened individuals’ sense of powerlessness, increasing their perception of risk. And it is in this cultural context that the Spanish Flu itself became ever more fearsome. Not just statistically – although epidemiologists did first start increasing the death toll in the 1990s, from 20million to 30million in 1991, before, in 1998, revising it upwards again, to between 50 and 100million. But figuratively, too. For the Spanish Flu was not just a terrifying metaphor for human fragility; it was now also becoming an apocalyptic figure, a sign of the catastrophe to come.

The apocalyptic imagination

The titles of the books published at the turn of the millennium are tellingly doomladen: The Coming Plague, by Laurie Garnett (1994). The Monster at our Door, by Mike Davis (2005). These two are not about the Spanish Flu as such. Garnett focuses on relatively new infectious diseases such as Ebola and the Marburg virus, while Davis fastens on to the Avian Flu. But in both, the Spanish Flu looms over their narratives as a historical figure, which, much like the Beast in the Book of Revelation, will yield its full meaning in the approaching viral apocalypse. The Spanish Flu was being conjured up now as a sign of what is to come, an anticipation of, as Davis puts it, ‘a mutant influenza of nightmarish virulence’.

Little wonder the Spanish Flu was now generating its own publishing industry. Interest had never been greater. For instance, John M Barry’s The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History emerged in 2004; Gina Colata’s Flu: The Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus That Caused It, in 2011; and and Nancy K Bristow’s American Pandemic in 2012.

What Spinney characterises as an explosion in Spanish Flu historiography from the late 1990s onwards, ‘with economists, sociologists and psychologists interested in it, too’, was generated by the development of the expansion of the apocalyptic imagination. Over the past three decades, present-day anxiety, itself born of sections of society’s profound estrangement from, and dread of, modernity, has not only generated a fear of the future; it has started to make sense of the past in terms of the catastrophe too many are convinced is coming. The Spanish Flu has acquired meaning now, not just as a historical event, but as something closer to a prefiguration of our fate. Take Alfred W Crosby’s 2003 introduction to his seminal America’s Forgotten Pandemic:

‘We live in a world that has become in some ways a better place for nasty viruses and a worse place for us than it was in 1918… [O]ur “globalized” transportation systems increase the probability of natural pandemics of influenza. In 1918 the fastest way to cross oceans was by steamship. In 2003, thousands of us daily and tens of millions of us annually make such trips in aircraft at speeds not far short of that of sound, carrying with us in our lungs and bowels, on our hands and in our hair, micro-organisms of all kinds, including pathogens. We are all, so to speak, sitting in the waiting room of an enormous clinic, elbow to elbow with the sick of the world.’

In other words, the Spanish Flu is not only the deadliest disease event in human history; it also prefigures the even deadlier one to come – despite all the obvious advances in medicine and public health. Here is Spinney:

‘ The Spanish flu was an example of what today we would call, with appropriate avian overtones, a black-swan event. No European thought that black swans existed until a Dutch explorer discovered them in Australia in 1679, but as soon as he had, all Europeans realised that black swans had to exist, since other animals came in different colours. Likewise, though there had never been a flu pandemic like 1918 before, once 1918 had happened, scientists realised that it could happen again.’

Throughout the reams of recent influenza literature, the same apocalyptic temporality is unfailingly at work. The present is conjured up as a site of crisis, pregnant with the future pandemic catastrophe the past has long been anticipating. Today’s prophets of pandemic point to the world’s densely packed urban areas, to industrialised farming practices and to mass, global travel, and they see something approaching sin. And they point more broadly to our levels of CO2-emitting production and consumption, and they see something to be avenged. Little wonder, some even seem to have been urging on the viral armageddon. Or at least excitedly expecting it. ‘The world is living on borrowed time’, wrote Mike Osterholm, the director of the Centre for Infectious Disease Research at the University of Minnesota, in 2016.

This apocalyptic temporality even started informing policymaking from the early 2000s onwards, in the form of so-called ‘preparedness’ (a phenomenon expertly critiqued in Carlo Caduff’s Pandemic Perhaps (2015)). So an EU report in 2005 states that ‘with increasing globalisation and urbanisation, epidemics caused by a new influenza virus are likely to spread rapidly around the world. The previous three pandemics occurred in 1918, 1957 and 1968 and although it is not possible to predict when an influenza pandemic is likely to occur, the risk is considered real enough to justify preparations being made.’ A document as supposedly sober as the 2014 ‘UK Pandemic influenza response plan’ also imagines our potential future in terms of a ‘1918-type pandemic’. And even during today’s Covid-19 crisis, it has been reported that policymakers were alarmed ‘by a study by Chinese doctors in the medical journal, the Lancet’, which suggested the lethal potential of the virus ‘was comparable to the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic’.

It is an incredible transformation. In the 1920s, the Spanish Flu had been experienced and understood as an outbreak of a particularly nasty disease. One hundred years later, it has become far more than that. It is now both a projection of our existential vulnerability, and an anticipation of our coming disaster.

The present crisis

In a sense, historical consciousness will always involve interpreting the past in terms of an individual’s and a society’s orientation towards the future. It’s why history continues to be written. It’s why events and struggles long obscured are constantly being illuminated – because of the light cast by the present. The historian, wrote EH Carr, is motivated by contemporary interests, intentions and motives – they’re the ‘bees in his bonnet’. Which is precisely why the histories of the Spanish Flu written by the likes of Spinney or Honigsbaum are so compelling. Their bonnets are buzzing. Their heads are alive with the concerns, interests and fears of the contemporary world. And, as a result, the Spanish Flu has been revealed to us as never before: as a bloody, complex spuming nightmare.

But there is a problem because of the extent to which contemporary historical consciousness tends towards the apocalyptic. It means the past is increasingly interpreted as little more than an anticipation of the imminent catastrophe, be it global warming, or, its close cousin, the global pandemic. For this is what the Spanish Flu now is: a mere sign of the end. It has lost its historical specificity, and has been reduced in broader cultural discourse and policy documents to a foreshadowing of the ‘next pandemic’, the ‘big one’, the disaster.

But as Caduff points out, the apocalyptic imagination doesn’t just reduce history to the status of semi-biblical allegory. It erases the present, too, simultaneously reducing and inflating successive outbreaks of disease to the level of the Spanish Flu. We saw that in the political and media overreaction to Bird Flu in the late 1990s, SARS in the early 2000s, and Swine Flu in 2009. So, here’s the question: could it also be the case that, thanks to the apocalyptic imagination, Covid-19 has also been turned into fulfillment of the Spanish Flu’s prophecy? In other words, has the apocalyptic imagination, feeding off the image of that devastating 1918 pandemic, created an apocalypse from a mere disease?

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

(1) America’s Forgotten Pandemic, by Alfred W Crosby, Cambridge University Press, 2003

(2) The Pandemic Century: A History of Global Contagion, by Mark Honigsbaum, Penguin, 2020

(3) Viral Modernism, by Elizabeth Outka, Columbia University Press, 2019

Pictures, unless otherwise stated, published under a creative commons licence.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.