Don’t sacrifice freedom at the altar of safety

It’s not fear but the quest to be safe that risks condemning us to a life in lockdown.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

It is clear that many people throughout Europe and beyond really fear the threat posed by the coronavirus. So much so that the vast majority have willingly abandoned their way of life, given up their rights and fundamental freedoms, and accepted a government-imposed lockdown – all in the name of protection from the threat of infection.

There was very little discussion and debate in the UK and elsewhere about the unprecedented steps that have been taken to contain the threat posed by the pandemic. One of the most striking symptoms of the public’s passivity in the face of the demand for a lockdown was its unhesitating willingness to accept the shutting down of schools. Schools had never been shut down before, not even during wartime. The continued education of children was deemed too important, even at times of national emergency. But no more, it seems.

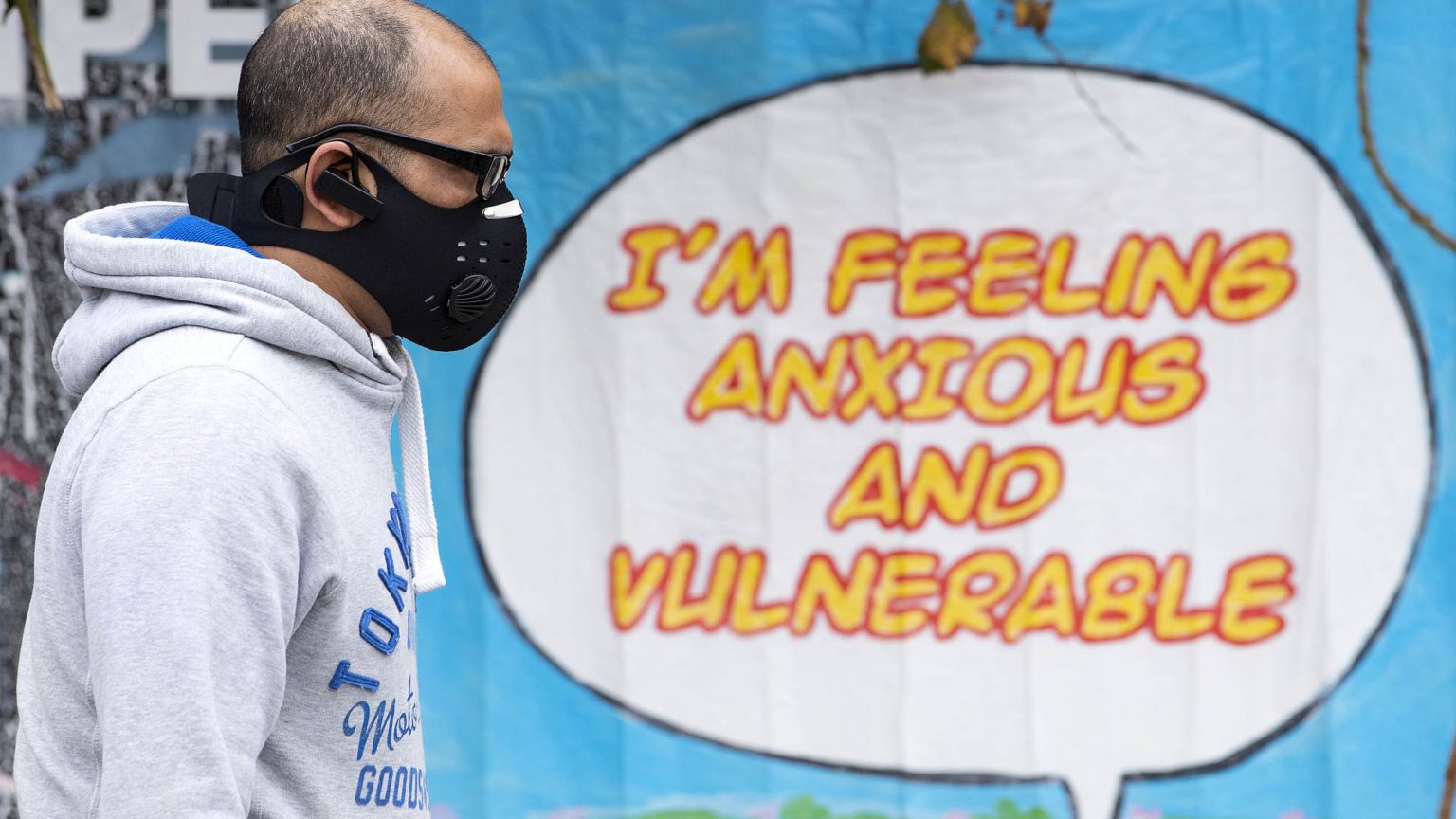

While governments were delighted that a fearful public was so ready to exchange its freedoms for the promise of safety, they now have a new problem — namely, that citizens have become too anxious to leave their homes when the lockdown ends.

Again, people’s attitude to schools and their reopening is telling. Many teachers and parents across Europe are said to be reluctant to allow their children to return to the classroom. As one UK-based teacher put it, they don’t want to be guinea pigs in a dangerous experiment. It is a sentiment shared by some Danish parents, who set up a Facebook group entitled ‘My kids are not going to be a guinea pig’.

Such is the widespread fear of Covid-19 that surveys show that the majority of the UK population would even like to extend this regime of confinement indefinitely. According to a recent YouGov poll, 57 per cent of respondents oppose the relaxation of lockdown rules, while only 11 per cent strongly support the relaxation of the rules. The willingness of such a large section of the population to stay locked up shows that many find it difficult to deal with uncertainty and the perception of risk.

The most recent poll by Ipsos Mori shows that 60 per cent of the public would feel uncomfortable about using public transport, and going out to bars and restaurants, should ministers decide to relax the lockdown. What this response indicates is that, for a large section of the population, the stay-at-home message has worked too well. But this is not just a product of people’s fear — it is also a product of their yearning for safety and security.

This is why so many people seem willing to accept such a grievous loss of freedom – because they want to be safe. Surveys even indicate that many are now content with their lot, and are less fearful now than at the beginning of the lockdown. So, according to YouGov, on 23 March, at the start of the lockdown, 36 per cent said they were fearful. By 27 April, this percentage had fallen to just 21 per cent.

Surveys and polls offer only limited insights into the cultural and psychological dynamic at work. It is therefore likely that there are reasons beyond fear of infection that account for the unprecedented accommodation of millions of people to a life under a lockdown. Indeed, what this may also show is the extent to which, for a section of the public, the imperative of safety now governs virtually every dimension of their life.

This society-wide preoccupation with safety is not simply a response to the current pandemic. As I explain in How Fear Works: The Culture of Fear in the 21st Century, the meaning of safety has expanded to the point where it guides virtually every aspect of life. It has become the dominant value of society.

It is worth clarifying what we mean here. There is a fundamental difference between what we value – safety and security – and moral values, such as freedom, justice or courage. Safety has both a subjective and an all-encompassing quality, to the point where it encourages a survivalist mode of behaviour at the expense of moral values.

This is because survivalism deprives important moral values, such as courage, of their meaning. Historically, the virtue of courage was regarded as the most effective antidote to fear. Western society still holds courage in high regard. But in everyday life we have become so estranged from this ideal that we do very little to cultivate it. In effect, the ideal of courage has been downsized, reduced to just another instrument in a self-help toolkit. The phrase ‘having the courage to survive’ captures its diminution. It suggests that merely living with distress and pain – the death of a loved one, perhaps – is in itself an act of heroism. The very ordinary experience of surviving a loss is presented as courageous.

Paradoxically, the quest for safety actually enhances people’s sense of insecurity. Every human experience has started to appear as a potential safety issue. And the exhortation to ‘stay safe’ has become ritualistic. It has become a way of saying that we can never take our security for granted, and that we are constantly at risk.

The quest for safe spaces

Fear is both mediated and regulated through moral norms. Throughout the centuries, courage provided society with hope and confidence, and offered an antidote to the cultural power of fear. As the philosopher Hannah Arendt explained, courage not only provides society with hope — it also underwrites society’s capacity to exercise freedom.

Experience shows that the quest for personal safety is not simply a response to external threats. It is now increasingly a reaction to the internal turmoil associated with existential insecurity. Since existential insecurity is an integral element of the human condition – given we exist in a world of uncertainty – the quest for safety is likely to be never-ending. The downside is that it distracts people from attempting to gain a measure of control over their affairs. Control requires a willingness to attempt to manage and live with uncertainty. Unfortunately, the capacity for dealing with uncertainty has been undermined by a culturally induced sense of helplessness.

Human beings can never entirely lose their aspiration for control. But during the pandemic, this aspiration has often assumed the caricatured form of hoarding stocks of toilet roll and tinned tomatoes. Moreover, for some, staying at home actually offers the illusion of control. To make matters worse, official policies have combined with media alarmism to reinforce the public’s obsession with safety. And in doing so, they have weakened people’s capacity for exercising control.

One of the most unattractive features of the deification of safety is that it tends to subordinate the value of freedom. Within the contemporary Western moral framework, safety and security are first-order values, while freedom is, at best, reduced to a second-order one.

Throughout history the relationship between freedom and safety has been a subject of debate. In numerous instances the very human impulse to achieve safety was used as an excuse to limit the exercise of freedom. This point was recognised by Alexander Hamilton, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. ‘Safety from external danger is the most powerful director of national conduct’, he wrote in November 1787. And he warned that ‘even the ardent love of liberty will, after a time, give way to its dictates’, which will ‘compel nations’ to ‘destroy their civil and political rights’. With a hint of fatalism, Hamilton suggested that ‘to be more safe, they at length become willing to run the risk of being less free’. Another Founding Father, Benjamin Franklin, was unequivocally against the practice of trading in freedom for safety. He famously remarked that, ‘those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety’.

Supporters of the freedom / safety trade-off claim that the liberties people enjoy need to be balanced with a community’s need for security. This argument has been raised and re-raised by authorities throughout history. Relieving people of the burden of freedom in order to make them feel safe is a recurring theme in the history of authoritarianism. (A version of this argument was elaborated during the post-9/11 ‘war on terror’.) On both sides of the Atlantic the exigencies of safety and security are used to justify laws and procedures that limit civil liberty. One of the most troubling dimensions of this development is the relentless trend towards the colonisation of people’s private lives. Advocates of expanding intrusive instruments of surveillance actively promote calls for a trading-off of privacy for safety (1). In many instances, citizens have been convinced to accept Big Brother watching them in order to keep them safe. Indeed, many citizens during the pandemic have become Little Brothers, happily keeping an eye on their neighbours. After one month of lockdown, it was reported that police in England and Wales had fielded nearly 200,000 calls from members of the public snitching on their neighbours for lockdown breaches.

Covid-19 constitutes a serious threat to human health. The challenge it poses is how to protect people from the threat posed by this virus without sacrificing their freedom. Once the exercise of freedom is perceived as unsafe, and a threat to human health, society is in trouble. Arguments for a trade-off between the two, deprive freedom – in any of its forms – of moral content. Moreover, depriving people of freedom does not make anyone feel genuinely safe. That is why after weeks and weeks of living in a state of lockdown, so many people have become anxious about stepping outside their doors, and living freely.

We can never be 100 per cent safe. But by stepping outside of our homes, we can begin to live as free citizens again. We can also begin to take control, get on with our lives, and learn to contain the threat posed by Covid-19. No power on earth can do more to strengthen our ability to deal with fear than freedom.

Frank Furedi’s How Fear Works: The Culture of Fear in the Twenty-First Century is published by Bloomsbury Press.

(1) See Terrorism and the Politics of Fear, by David Altheide, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2017, p42

Picture by: Getty

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.