Children are suffering under this lockdown

We must make sure they do not become fearful of the outside world.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

When my eldest son was four, his favourite CBeebies programme was Come Outside. In every episode, Auntie Mabel, played by Lynda Baron, and her fluffy dog Pippin discovered new things: insects, how pencils are made, where woolly jumpers come from. Auntie Mabel goes into the big wide world – by foot or by bus or by her spotted airplane – finding things to explore, rather than things to fear.

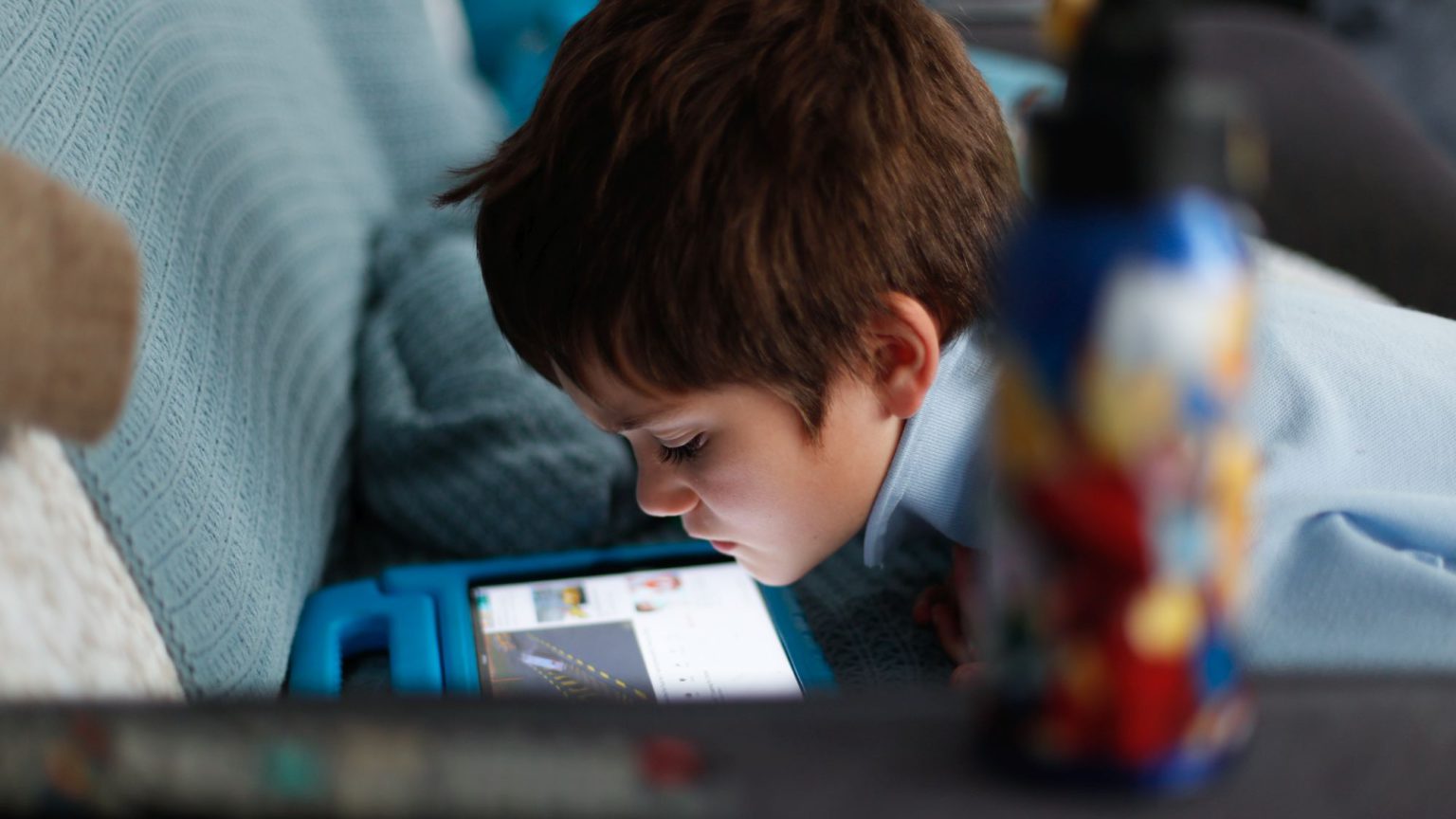

Watching it again now with my youngest, it feels strangely radical in this Covid-lockdown world. And it reminds me that children need to explore the world around them, in person, not through a screen, regardless of how idyllic the content.

We’re lucky in that we live in a house with a roomy garden, with plenty of space to toddle about, climb, swing, jump and play with sticks. But not all children are in the position where they have safe places to run around anymore. Many live in tower blocks without much green space, and now that playgrounds have been shut, and we’re being told to ‘stay local’ rather than drive to the seaside or countryside, the possibilities for hundreds of thousands of urban children to explore the world have been seriously limited.

On top of that, they’re not allowed to see friends outside their family. Children will lose all contact with peers, and no one seems to know for how long.

As they are being told to stay at home to ‘save lives’, children are starting to feel frightened of going out. One in five primary-school children are now afraid to leave their homes, according to scientists at the University of Oxford. The university is conducting a survey to track children’s mental health during the pandemic, and the findings are based on the 1,500 parents who are taking part so far.

It’s the youngest children who are most worried, the survey reveals. Fear of picking up the virus, or of passing it on, is making children nervous, even though data indicates that children are not likely to suffer severely from Covid-19, and the likelihood of them being ‘super spreaders’ is hardly an uncontested claim. This is why in countries such as Denmark and Norway schools are due to reopen this month, and Swedish schools have remained open throughout the pandemic. British scientists have also questioned the closure of schools, saying schools may not play a substantial role in spreading the virus.

As Fraser Nelson points out in the Telegraph, the British people took the government’s message of staying home surprisingly seriously. Now that everyone has been told not just to keep apart from others, but to stay at home and only go out if strictly necessary, we shouldn’t be surprised that children take this to heart, too, and start to fear the outside world.

Looking at how Norway has communicated with the public about social distancing may question the British focus on staying indoors. In Norway, playgrounds have remained open, and children and young people are still allowed to meet others in small groups.

There is also no limit on the number of trips outside per day, and the public has been advised to get out and about. ‘Fresh air is important’, according to Linda Granlund at Norway’s Health Directorate. ‘We would like to advise anyone who is not in quarantine to get outside to go for a walk or a run’, she says.

And why not? Viruses thrive in closed environments. Plus exercise and social connections are important – as is, sadly, getting a break from less than ideal home environments for many children. These are not luxuries or non-essential parts of children’s lives. It takes little imagination to envisage that deprived children will suffer the most from being told to stay indoors for weeks on end.

Let’s hope we can develop smarter ways of dealing with Covid-19, which take into account the needs of children. Children need the outdoors, whether it’s an inner-city playground or the wild woods, to develop into healthy adults. They should be encouraged to embrace the wider world, even amid this crisis.

It may take a drastic change of messaging, but we cannot risk these emergency measures becoming ingrained in our children’s psyches.

Kathrine Jebsen Moore is a freelance writer in Edinburgh. She regularly contributes to Quillette, the Spectator and writes a monthly column for Minerva, a Norwegian conservative magazine.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.