Coronavirus Bill: the greatest loss of liberty in our history

Silkie Carlo, director of Big Brother Watch, on the alarming authoritarianism of the government’s new powers.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

The Coronavirus Bill, having sailed through the House of Commons, is expected to become law today. The Bill gives the government and the authorities unprecedented new powers, unheard of in a democracy during peacetime. Silkie Carlo, director of Big Brother Watch, has warned that these powers are unreasonably draconian, and could be here to stay long after the threat of the virus has dissipated. spiked caught up with Carlo to find out more.

spiked: What’s wrong with the Coronavirus Bill?

Silkie Carlo: This is a 329-page bill conferring extraordinary powers to the executive, which is being rushed through parliament in just three days. This is completely unprecedented. It leaves us with the greatest loss of liberty that we have probably ever had in this country on the back of one piece of legislation in peacetime.

The duration of the powers is one of the first things that stands out. The bill was drafted to allow its powers to last for two years – an extremely long period of time for such extreme emergency powers. Big Brother Watch ran a campaign over the weekend saying two years is too long and thousands of people emailed their MPs. The government has conceded an amendment which allows for a review after six months. But the way this has been phrased means that, essentially, the government can come back in six months and say that the powers need to continue. It would require parliament to vote against the government to try to get rid of the bill. Obviously, the numbers in parliament are really stacked against that at the moment.

If we are honest with ourselves, these powers are going to be here to stay. The virus isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. Crisis follows crisis. The slippery slope might be an overused term, but it is very, very difficult to reverse the handing over of such extraordinary powers.

The other concerning thing is that we already have structures in place to deal with emergencies, namely the Civil Contingencies Act. Under the Civil Contingencies Act, government can lay regulations which have to be reviewed within seven days, but they can last for up to 30 days. And that is an appropriate mechanism for measures like arbitrary detention powers or any powers which you would never normally find acceptable in a democracy.

But that Act hasn’t been used. As Matt Hancock said repeatedly yesterday in the house, there is no plan to use that Act. This Coronavirus Bill actually comes from an earlier draft of an influenza pandemic bill and so this is not simply a product of making do in the circumstances. Obviously, everyone in parliament and everyone in government is faced with extraordinary circumstances. But the approach they have chosen is really worrying.

I was relieved to see lots of MPs in parliament raising questions, including Conservative backbenchers, asking why the Civil Contingencies Act hadn’t been used. And the response given by the government was, I’m afraid, simply not true. Jacob Rees-Mogg said the coronavirus pandemic doesn’t qualify as an emergency under the Contingencies Act because it has been known about for too long. But that is just not the case. David Davis asked the Speaker’s Counsel, which gives legal advice to the Commons, whether that was actually the case. And the Speaker’s Counsel said unequivocally that the powers under the Civil Contingencies Act – which was written by the Counsel – are absolutely appropriate for the current emergency. I think that the Speaker’s Counsel note is going to be a very significant document in the months and years to come, unfortunately.

spiked: What powers does the bill have?

Carlo: The standout thing in the Coronavirus Bill is its detention powers. The bill confers arbitrary detention powers to the police, immigration officers and public-health officials. They can detain and isolate ‘potentially’ infectious people. Potentially infectious people can be literally anyone. As we have seen from the government reports, up to 80 per cent of the public could be infected with coronavirus eventually, many of whom will be asymptomatic. There is no explanation as to how the authorities will determine whether someone is potentially infected. For all intents and purposes, it allows for arbitrary and indefinite detention. Any member of the public, including children, could be forcibly detained, isolated, quarantined in an as yet unidentified location. It also enables authorities to forcibly take biological samples from people for testing.

I don’t want to suggest that the powers will be used in as apocalyptic a way as the phrasing would permit. But of course, it would still be the height of naivety to hand these powers to the authorities, especially in a time of crisis in which people are acting rapidly and reactively. In a democracy, you do not normally give those kinds of extraordinary powers without the bare minimum of safeguards or at least explanations.

Another major power in the bill is around dispersal. Under the Coronavirus Bill, authorities can shut down events, gatherings, premises, and not only force people to leave and go into isolation facilities, but they will also have the power to make people stay in a place.

There is also an extension of detention powers under the Mental Health Act. So people can now be sectioned on the advice of a single doctor rather than two doctors, as is currently the case. This is at a time when the population is under undue psychological pressure. Other parts of the bill allow social-care standards to be drastically relaxed, so we will see people suffering more.

One of the worrying differences between the Coronavirus Bill and the emergency powers under the Civil Contingencies Act is that there is no exemption for political gatherings or political assemblies. When we are talking about a massive expansion of ministerial powers for two years, and a huge step-change to our politics, that is really worrying. It would not be difficult to amend the bill to have an exemption for industrial action and strikes, as exists in the Civil Contingencies Act, because obviously this is where there is the most obvious potential for abuses of power. We as a public must, should we need to, be able to say, in several months’ time, that the government has got it wrong, that we want a different approach, that the coronavirus measures aren’t right or they are not being used in the right way. Our fundamental ability to express that could be taken away.

spiked: What concerns do you have in relation to surveillance in this bill?

Carlo: I was quite surprised to see the relaxation of surveillance safeguards. Essentially the bill does two things. First, it allows for the appointment of temporary judicial commissioners. Judicial commissioners are typically retired judges who oversee surveillance warrants. Secondly, it extends the time limit that they have to review urgent warrants.

This may seem quite academic, but we need to be extremely cautious about this. Urgent warrants, on the one hand, are incredibly important for protecting national security. And of course, you need to have a provision for urgent warrants. But because the way that they are drafted currently is relatively lax, they are open to abuse. And given the enormity of the surveillance powers that we have in the Investigatory Powers Act already, we are talking about the potential for population-level surveillance of devices, tracking, interception, all kinds of powers. The bill will lower the safeguards to using those powers.

The potential for abuse is extreme. In countries like China, Iran, Israel and Russia, authorities are already tracking individuals’ phones to make sure that they comply with quarantines. This is something that’s particularly relevant to us in the UK now that we are basically on lockdown. We are allowed out once per day, and only for specific purposes. There are questions about how that’s going to be enforced, and I hope it is going to be in a proportionate way. But we have seen phone tracking used in other countries as part of that. The extraordinary thing about this is, in the UK, we wouldn’t even know about it if the government was doing this because our surveillance powers are so extreme – they are completely covert and completely secret. If someone working at a telco like O2 or another network were to disclose that they were tracking us, that person could go to prison for a year.

spiked: Is there a threat to liberty more generally during the coronavirus emergency?

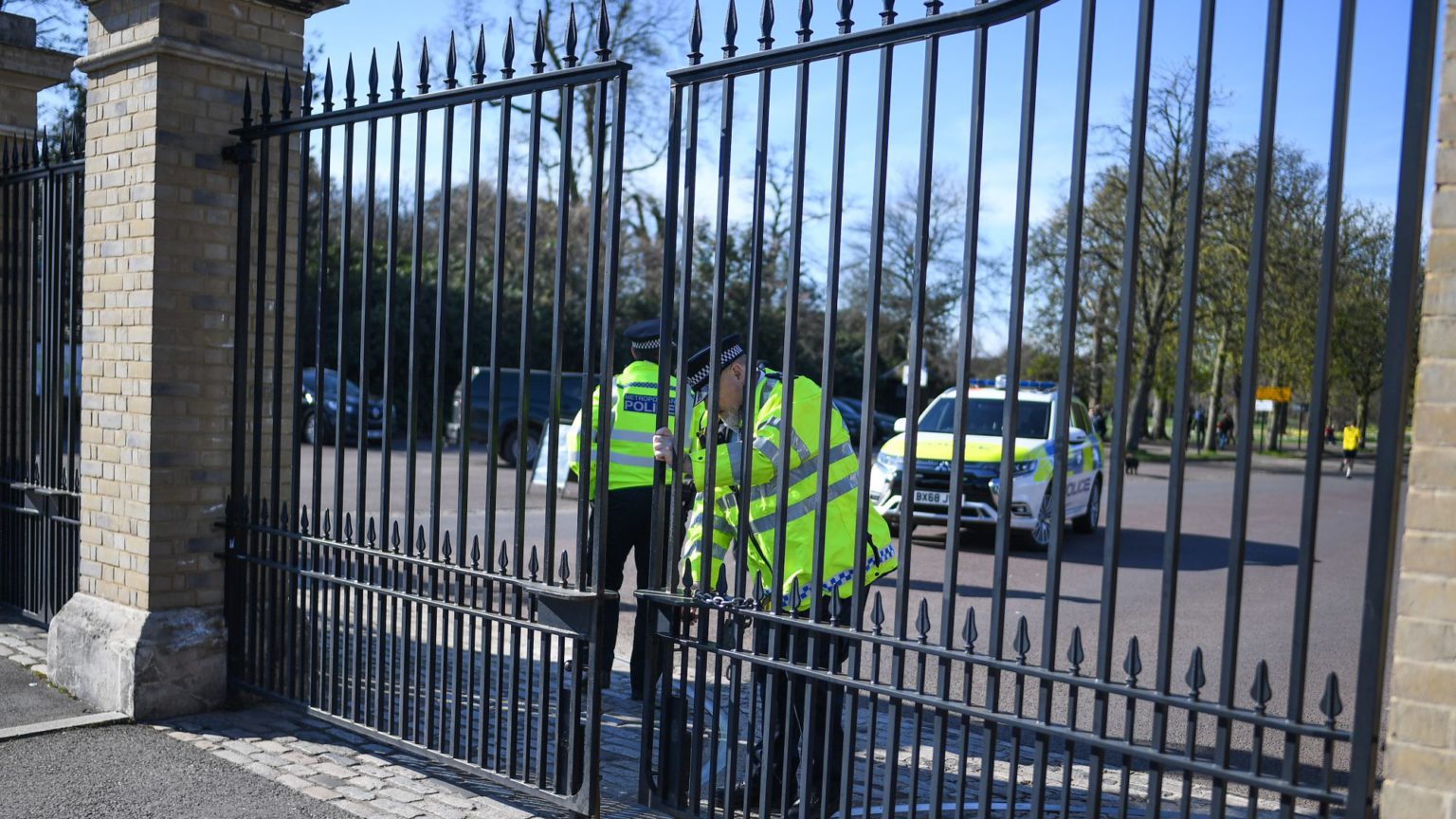

Carlo: Of course, measures need to be taken to make sure that people are safe and we have to defer to experts about that. And I really hope that the decision to lock down the country has been made on the basis of expert advice, and not because of the clamour to ‘do more’ by the Twitterati and whoever else. Those people have themselves gone out to parks and taken photos of other people in parks and have said things like, ‘Oh my God, I can’t believe these plebs aren’t all at home!’. This is a really difficult time for everyone. People need to go out, to get fresh air, to go for a walk, to walk their dogs and to get exercise. And I do think there has been a worrying level of panic about people doing these basic necessary things in a relatively safe way (though I appreciate that it hasn’t always been the case). The dangerous thing about aimless calls to ‘do more’ is that if government caves into those kinds of pressures – when they are unevidenced and aimless and driven by a general sense of panic – then we are going to end up in a really dangerous place.

The unique thing about this crisis is that it requires the public’s cooperation. State power alone will not get us through it. It demands behavioural change from all of us. And I have been really surprised to see the amount of behavioural change there has been already. It is weird to see central London empty like a ghost town. People are wearing masks, scarves over their faces and gloves. People are working from home and have completely changed their pattern of life. I think the British public has been extraordinarily cooperative and resilient in dealing with this. And I hope that we continue to be during this lockdown.

Three weeks is going to be a long time, we are all going to really feel it. And I just hope that we don’t find ourselves having to do things like filling out a form to leave the house, as is happening in other parts of Europe. That would be incredibly depressing.

Silkie Carlo was talking to Fraser Myers.

Spare a fiver, support spiked

Become a £5 per month donor today!

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.