Long-read

Italy: the crisis that could go viral

Coronavirus threatens to turn Italy's economic and financial crisis into a global one.

The coronavirus is tipping Italy into an economic and financial crisis that has the potential to trigger worldwide financial mayhem. Italy is the weakest major link in the global economic chain, which was already under great strain in 2019 and is now ominously fraying at other key global nodes: China, Japan, South Korea and Germany.

Even if the coronavirus (officially named Covid-19) is itself contained in the coming months, a financial crisis that radiates from an Italian epicenter is already at hand. But European leaders seem keen to carry on as normal. Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank (ECB), says the coronavirus has yet to cause ‘a long-lasting shock’. Her staff, and that of Paolo Gentiloni, the EU’s economic commissioner, are still pondering over how serious the problem is. This is to indulge in perilous complacency. The ECB and European governments are failing to face up to the danger posed by an Italian financial crisis. It is past time to prepare the global effort that will be required to contain its fallout.

The Italian economic and financial fault line

Italians have become poorer in the two decades since Italy adopted the euro as its currency. The country’s economy remains in near-perpetual economic recession.

Italy’s dysfunctional political system has the feel of a fast-flipping pizza game. For nearly half a century, Italian governments have failed to invest in the country’s future. Everyone understood that Italy would struggle to survive without the crutch of its ever-depreciating currency, the lira. But the hubris of European leaders brought Italy into the stranglehold of the eurozone, where the euro is too strong for the Italian economy, and the real interest — the interest rate adjusted for inflation — is way too high for an economy that does not grow.

The coronavirus has hit Italy cruelly, not just in alarming human terms, but by threatening to disable the provinces of Lombardy and Veneto. These are the production hubs that, over the past two decades, have prevented an even grimmer economic fate for the Italian economy.

Italy’s financial vulnerabilities are huge. The Italian government’s debt burden, at around 2.4 trillion euros, is larger than Germany’s, which sits at two trillion euros. The Italian government’s debt-to-GDP ratio has been inexorably rising. The Italian banking system is sitting on a gargantuan pile of financial assets, amounting to around five trillion euros. While the many decrepit Italian banks have sold (often for pennies) a large fraction of the loans that their borrowers were not repaying, bank profitability is anemic because of the extremely low interest rates that banks can charge, and because borrowers are still struggling in a zero-growth environment. The market-to-book value ratios of even Italy’s strongest banks — Intesa Sanpaolo and UniCredit — remain well below one, implying that markets think that a large part of the assets these banks hold will eventually be written off.

Matters will get worse

The coronavirus has struck the global economy at a moment when it was already weak. And a disease attacks the feeble most ferociously.

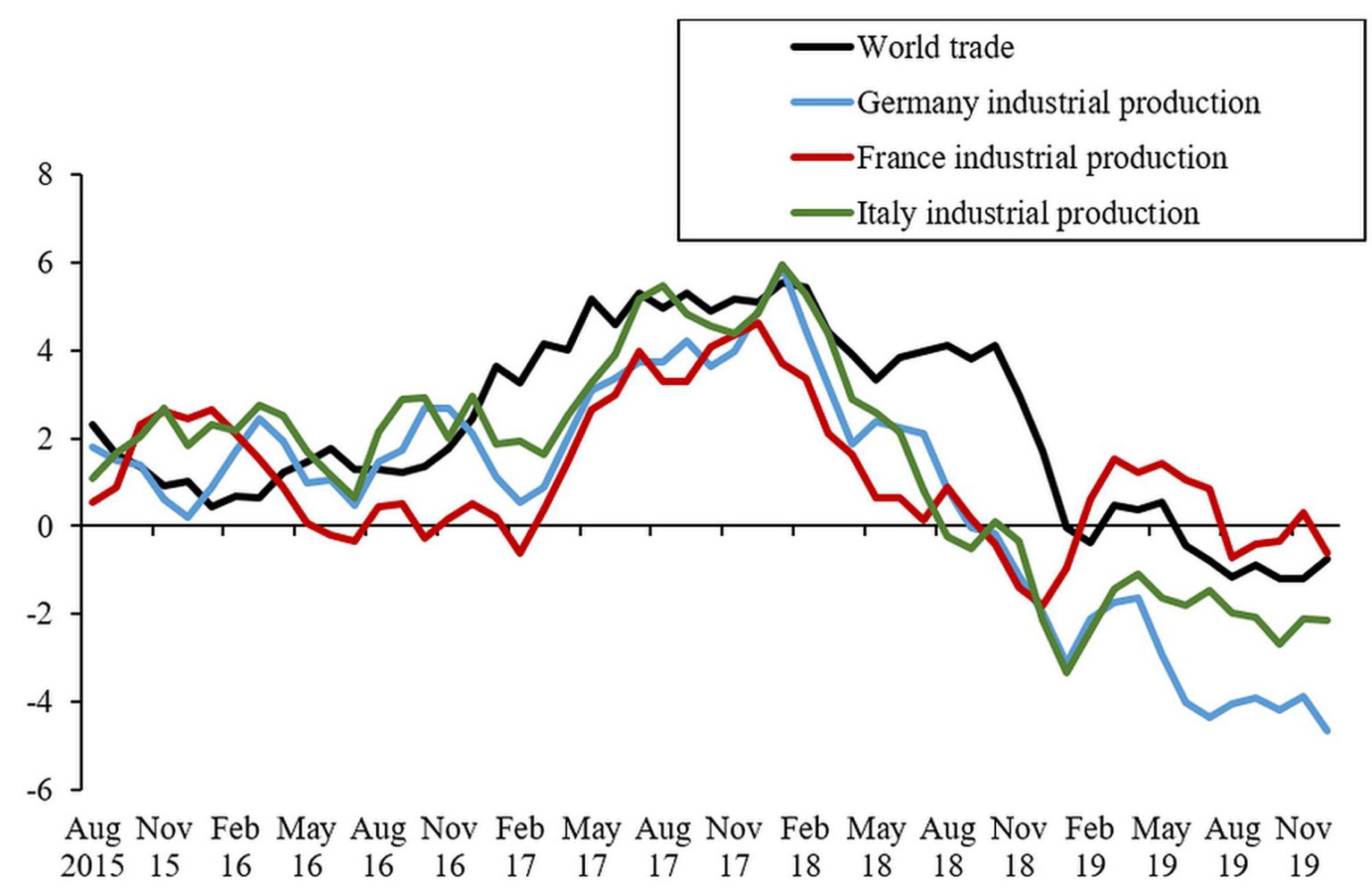

Italy and other European economies – crucially dependent on global trade – have been under mounting economic stress since early 2018, when world trade began to slow down (see figure below). The world-trade slowdown, in turn, was the consequence of the Chinese government’s decision to stop pumping up its domestic financial system for fear that domestic property and financial vulnerabilities could get dangerously out of hand. As the Chinese economy – with its huge presence in the global trading system – cooled down, world trade began to decelerate. In 2019, the US-China tariff escalation put a further dampener on world-trade growth, which pushed European economies into near-recessionary conditions. Thus, the global, and especially the European, economic situation was precarious well before the coronavirus struck.

Coronavirus has thrown into stark relief China’s dominating role in world trade. China is the key node of global value-added chains. Chinese factories produce parts for mechanical and electrical industries, as well as ingredients for the pharmaceutical industry, to keep the world’s factories humming. With several Chinese factories in shutdown mode, manufacturers around the world – especially in other major production hubs that rely on China – are shuddering to a stop. Already, car factories in South Korea, unable to source parts from China, are feeling the pain. Meanwhile, the spread of coronavirus to South Korea will interrupt production at its semiconductor and other electronic-parts factories, disrupting supplies to producers who assemble consumer and industrial products.

In Europe, Germany, the traditional anchor of European economic health and arbiter of European political horse trading, is at great risk. In 2019, the German economy suffered from the multiple blows of slowing world trade and the accelerated shrinking of its car industry, as consumers turned away from Germany’s vaunted internal combustion-based cars, rendering technologically obsolete large parts of an industrial ecosystem centred around auto production. Now, as the Chinese economy shrinks in the first half of 2020, German car and machinery producers will lose their most bountiful market of recent years. And as the German economy contracts, several Italian producers sustained by sales to Germany will suffer.

While China, Japan, South Korea and Germany can handle half a year of economic contraction, Italy cannot. Italy has no fiscal or financial fallback once it slides from its current economic and political torpor into a deep economic contraction. The government’s debt-to-GDP ratio will rise rapidly, pushing up interest rates on Italian debt and making repayments even more onerous. The chaotic banking system will face losses that it cannot bear and the government cannot shoulder. The public and private Italian defaults will cause their creditors to default, triggering an ever-widening global cascade of defaults.

A squabbling Europe

The eurozone members managed to cope with the financial crisis in 2010. But the countries in crisis — Greece, Ireland and Portugal — were small. At that time, even the Spanish government’s debt was only a third of the Italian government’s debt. And Germany, as the rescuing knight, was at the peak of its economic and political strength. The German chancellor, Angela Merkel, although frustratingly slow to respond, nevertheless managed to keep the eurozone ship afloat.

Today, Europeans are fighting over pennies for the next EU budget. The divisions are palpable on the critical issues of migration and strategic responses to China, Russia, and the US.

Germany, the erstwhile European leader, is in a precarious condition. As its economy struggles against great odds, there is also a big question mark hanging over the future of the giant, scandal-ridden Deutsche Bank, with US and UK regulators perennially monitoring it for fraud and money laundering. Markets are now valuing Deutsche Bank’s assets at one-third of the value recorded in the bank’s books.

All this is exacerbated by Germany’s bitterly fragmented politics. For financial leadership, Germany used to be the only game in town. Now, with a hobbled Chancellor Angela Merkel in a nation tearing itself apart politically, there is no one to take the role that German chancellors have played to knock European heads together in the past. And no one else has the political or financial stature to step into that role, least of all the divisive and volatile French president, Emmanuel Macron.

In an Italian economic and financial crisis, the EU’s cumbersome financial-rescue systems will be tested mercilessly. Any rescue effort will require, as a first step, an Italian bailout programme that puts the government on a tight and humiliating fiscal leash. The EU’s leaders bullied Greece, Ireland and Portugal into accepting such political subordination. Will the Italians bow to the same treatment and accept the same conditions?

If Italian politics is unable to deliver a credible domestic defence, will the ECB, going against agreed norms, nevertheless be tempted to use its money-printing authority to prop up the Italian government and financial system? Or, as is more likely, will the ECB be paralysed? For, amid a spiralling crisis and escalating market panic, the Germans and other ‘northern’ eurozone member states on the ECB’s governing council will dither. They would worry that if the ECB does bankroll Italy, and the Italians don’t pay the ECB back, the taxpayers in the northern member states could bear a recurring burden so large that even their apparently strong governments will face fiscal stress and credit-rating downgrades.

Time for global action

Make no mistake, we are poised at a crucial moment in global economic history. The rescue efforts from the global and European financial crises have left the firepower of central banks depleted. Everywhere, the economic recovery proved much weaker than after previous crises. Forecasters have grudgingly recognised that long-term growth prospects in the advanced and much of the developing world have sharply declined. The Italian epicenter is in a much more fragile economic and financial condition than at any time in the postwar period.

Today, only the US Federal Reserve System can inject a modest monetary stimulus. Governments would do well to coordinate a global fiscal stimulus through increased spending and tax cuts to buoy the international economy. But a Fed stimulus and national fiscal measures by themselves will be insufficient.

Well before monetary or fiscal stimulus kicks in, there will be a moment of reckoning. This will be the choice. Northern EU member states could agree to pay for Italy, with the knowledge that they will have to keep their cheque books open for a long time, inflicting significant, even long-lasting, damage to their own fiscal situations. Or they could stand back, hoping the problem will go away. In which case, the Italian financial system could go into a free fall, causing cascading debt defaults to race through the world’s financial pipelines. The crisis will almost certainly be larger than eurozone members can handle.

Of course, the worst may never come. But at this delicate moment, global preparedness for a full-scale financial response is essential. To do any less would be irresponsible.

Ashoka Mody teaches at Princeton University. The paperback edition of his EuroTragedy: A Drama in Nine Acts, published by OUP, is available in the US and soon in the UK.

Picture by: Getty

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.