Meet the Scottish nationalists who voted Leave

The SNP has a problem – many of its supporters also support Brexit.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

There is no doubt that the Scottish National Party is one of the wonders of global politics, having reached singularly impressive heights in the aftermath of the referendum on Scottish independence in 2014. It may have lost that campaign by a margin of 11 percentage points – or 383,937 votes – but its membership exploded from around 25,000 to upwards of 114,000, and has continued to grow until it overtook the Conservatives as the UK’s second largest party in 2018, around the time of Theresa May’s resignation.

Bucking a historical trend of disengagement, an unprecedented 85 per cent of the Scottish electorate flexed their democratic muscle in 2014. The SNP was subsequently catapulted from the fringes to the centre of the UK political landscape for the best part of two years. At the General Election in 2015, it obliterated the opposition by returning 56 MPs out of a potential 59.

Four years on, and it has launched its General Election 2019 campaign under the heading ‘Stop Brexit’. It has pledged, in the event it holds the balance of power at Westminster, to revoke Article 50 without a second referendum while, ironically, calling for a second referendum on Scottish independence. Its argument is that Scotland voted to remain in the EU, which conveniently overlooks the fact that Scotland also voted to remain part of the UK. It also forsakes the history of the SNP, which was, historically, Eurosceptic. Indeed, over a third of SNP voters still back leaving the EU.

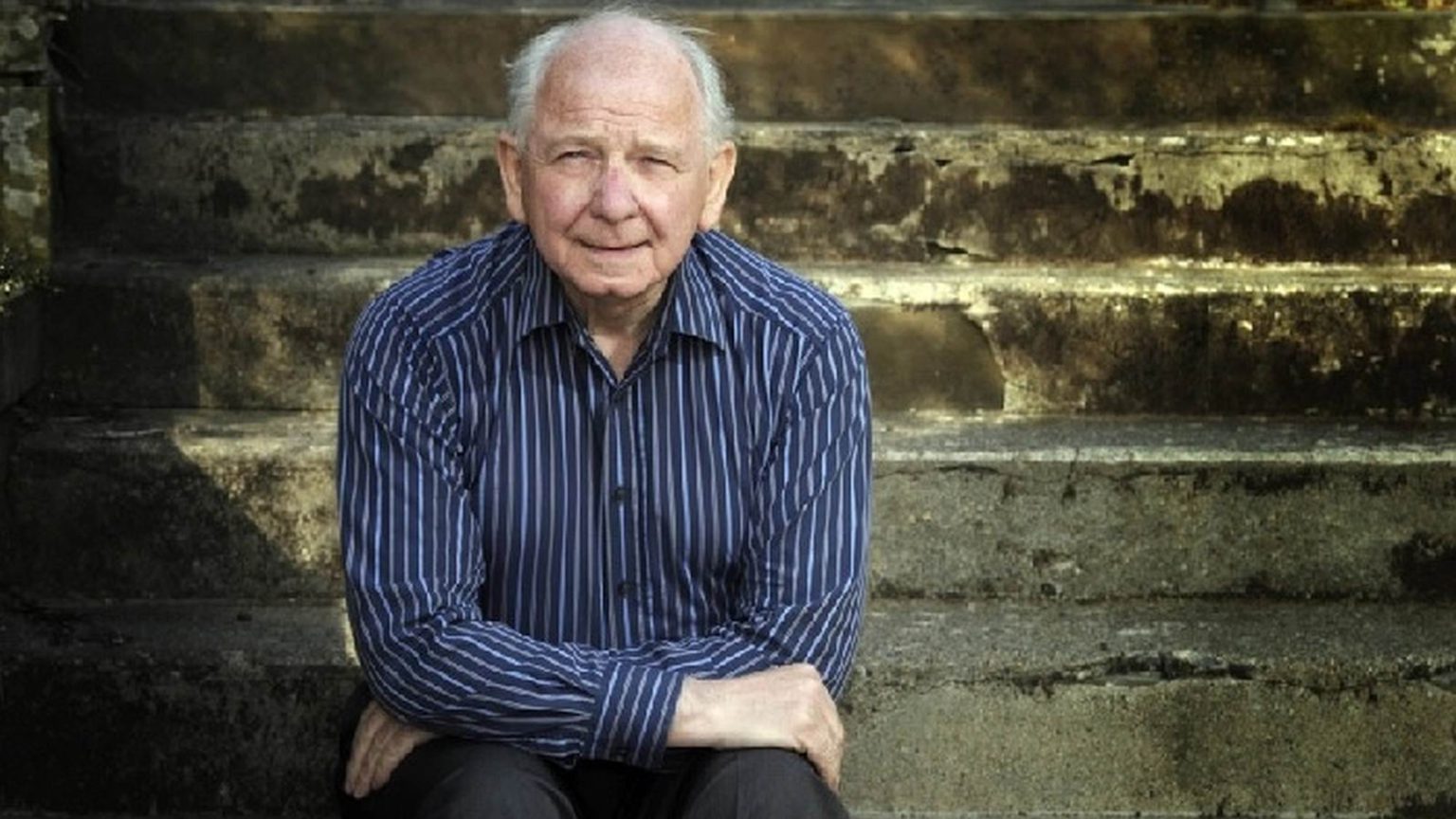

One of the cheerleaders for SNP Euroscepticism is Jim Fairlie (pictured above), who was the SNP’s deputy leader from 1981 until 1984. ‘My Euroscepticism’, he tells me, ‘was conceived with the Treaty of Rome, which was signed in 1957, and laid out the objectives of the European Economic Community [EEC]. It was clear even then it was about political union. I argued that the economics would drive the politics and that is what the Eurozone and single currency have done.’ He adds: ‘Some say the EU has changed but it hasn’t. It has only done exactly what it always said it would do.’

Fairlie is now 79 years old. He lives in Crieff, Perthshire, and joined the SNP in 1955 as a 15-year-old boy, for the same reason, he says, as other traditional nationalists – because the SNP was the only party that stood for independence. Today’s incarnation, however, prompts little enthusiasm: ‘It makes me despair to have seen the direction of a movement in which I spent over three decades. Throughout the tenure of my membership, there were large sections of the party who were Eurosceptic. And even when the SNP began to soften its view on independence towards the late 1980s, there was still strong opposition to the EU.’

He reflects on the moment the SNP began to shift its perspective on what was then the EEC. He says: ‘We turned up to the SNP conference in Inverness in 1988, and there was a banner emblazoned with the words “Independence in Europe”. At this point, there was little centralisation and no single currency, but I stated consistently and fervently that it would become more centralised, more economically intertwined and more powerful.’ After a pause, he adds: ‘We never did discover who put that banner there.’

Fairlie continues: ‘In 1990, the issue of Europe came to a head when the [Eurosceptic] former SNP leader, the late Gordon Wilson, chose to stand down after 11 years.’ Wilson’s successor, Alex Salmond, subverted the party constitution, Fairlie explains, by preventing papers being sent to branches to open discussions on the EU, which would have been brought to the SNP’s national assembly. Despite having served as deputy leader, vice chairman for policy, and been on the executive committee for 20 years, it was then that he stopped identifying with the SNP: ‘Independence was no longer a priority and, after 35 years of membership, I left.’

The thing that most concerns Fairlie about the EU relates to his specialist subject – economics – which he taught at both school and college. He also worked in financial services for over 30 years. On this issue, he says: ‘The SNP argue that EU countries are independent and sovereign, but nobody can tell me which of the 19 members of the Eurozone can implement its own economic policies.’ He adds: ‘The answer is very simple – none. Not one of them has power over its own monetary policy, which deprives them of overall control of their economies.’

Like many traditional Eurosceptic nationalists, Fairlie described watching the SNP election campaign launch under the heading ‘Stop Brexit’ as ‘disheartening’. He ponders: ‘What happened to independence? Nationalists have become fixated with the EU.’ Fairlie is not alone in thinking this: ‘I receive many messages from traditional nationalists who are sick to the back teeth of this obsession. As long as the SNP is campaigning for membership of the EU, it is not campaigning for independence and that is why I cannot vote for it [on 12 December] nor on previous occasions, when I have not voted at all.’

Similarly troubled by who to vote for on 12 December is SNP Vote Leave founder Don Morrison. He tells me, however, that, ‘I will vote SNP, despite my strong disagreement with its EU stance, as I am very supportive of its domestic agenda and am proud of the Scottish Parliament and all it has achieved’. He adds: ‘Although I have serious misgivings over Nicola Sturgeon’s pledge to support [Jeremy] Corbyn, and feel this brings yet another dynamic to an already complex set of considerations facing voters, I could not vote for any of the other three candidates in my constituency.’

Morrison, who is 72, lives in Banchory, Aberdeenshire and voted for the Brexit Party in May’s European Parliament elections. ‘My position on the EU is supported by door-to-door canvassing for the SNP’, he tells me. ‘People raise the inconsistency of removing governance from Westminster only to retain the oversight of Brussels. When I am going round the doors, it is absolutely clear people are not stupid. They understand the notion of emancipating oneself from the governance of Westminster, but they do not want to be subservient to, or be expected slavishly to follow, Brussels instead.’

Morrison has been a member of the SNP for 53 years, having joined the party in 1966. He still has his first membership card. Like Fairlie, he remembers when the party was staunchly Eurosceptic. ‘I have always been a passionate advocate for Scottish independence’, he tells me, ‘and fully supported the SNP policy to vote against remaining in the EEC in 1975, which the UK had joined two years earlier. There are a sizeable number of Eurosceptics within the SNP, but some just remain quiet because they feel party discipline can be quite uncompromising.’

In the 2016 referendum, Morrison led the SNP Vote Leave campaign in the north-east of Scotland, where the Leave vote was at its highest. It also led to a significant return of Conservative MPs in the 2017 General Election. He says that, ‘in spite of the awkwardness of campaigning in opposition to my party, I felt it right to stand up for what I believe in and I thought it a pity to find party members who shared my point of view but who were too afraid to express it’. He also says that it is perilous for the SNP to overlook the almost 1.2million who voted Leave in Scotland in the 2016 EU referendum.

Jim Spence, known to many as a veteran sports broadcaster, has also been a long-standing supporter of independence, from both Westminster and Brussels. ‘I joined the SNP after [Margaret] Thatcher’s third victory in 1987, having concluded that the interests of Scotland were being swept aside by the perpetual reign of the Conservatives’, he tells me. ‘Under Thatcher, I saw British industry and manufacturing pillaged, from mining and steel to the docks, and I thought we can do things in a more equitable and just manner than this in an independent Scotland.’

Spence, who is now 64, lives in Dundee, and is rector of Dundee University, is still convinced of the case for Scottish independence. ‘I found various aspects of independence attractive’, he says, ‘such as the opportunity of fairer land ownership, being able to build affordable housing with reasonably priced mortgages, which reflected people’s real earnings, narrowing the differentials in terms of wages, and the chance to further democratise Scottish society by ensuring that power wasn’t centralised in Holyrood, but was able to be spread throughout the communities of Scotland.’

Spence was invited to Bute House by then SNP leader Alex Salmond and offered the opportunity to stand as a candidate in Dundee West in the 2015 General Election. He had stood for the SNP before – in a council by-election shortly after joining the party in the late 1980s – but he decided not to pursue Salmond’s offer. While his opposition to the EU was a factor in his decision not to stand, he says another reason was that ‘the SNP was not a particularly left-of-centre party, and there were some emerging and concerning shades of authoritarianism’.

When I ask what stoked the fires of his Euroscepticism, he answers immediately: ‘Greece!’ He explains that he always considered himself a socialist rather than a nationalist and, from that vantage point, struggled to identify a socialist case for the EU. ‘If you are a socialist’, he says, ‘you cannot truly say you care for people as much as you might like to think you care, while still affirming the existence of the EU. As someone who is of the left, I did not feel I could stand by and watch the working population of Greece being crushed and say nothing.’

Like many, Spence has been concerned by the caricatures of Brexit voters. ‘I struggle with the imbecility of the view that 17.4million voters can be characterised as racist, thick and stupid. There is a lack of civility in our political discourse and an absence of democratic decency.’ In terms of his voting intention, he says, ‘I have a Brexit Party candidate standing in my area. I could never vote Tory, so I’m left with the choice of voting for the Brexit Party, spoiling my ballot or voting for an SNP, which wants to withdraw from one union only to hand power to another.’

Lord Ashcroft conducted a survey in June 2016 highlighting that 36 per cent of SNP voters also voted to leave the EU. The challenge for the SNP is, having taken such a clear stance on EU membership, what will happen to those who notionally support its domestic agenda but cannot countenance a vote for a party that wishes to overturn the EU referendum result? Fairlie, Morrison and Spence all said they believe that the SNP vote, as well as its membership, will, at some point, fracture over the EU issue. Fairlie went further, stating that conversations about a new party are already underway.

It is clear that this issue is not going away. If Scotland was to succeed in holding another referendum on independence, the issue of EU membership would be front and centre, especially if the people of Scotland voted Yes. The passion for Scottish independence still burns bright. But the issue now relates to whose version of independence we are talking about.

Ewan Gurr is a commentator, consultant and columnist for the Evening Telegraph. Follow him on Twitter: @EwanGurr

Header picture by: the Scotsman / Johnston Press.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.