In praise of spite

Spite plays a key role in political life, and that can be good thing, too.

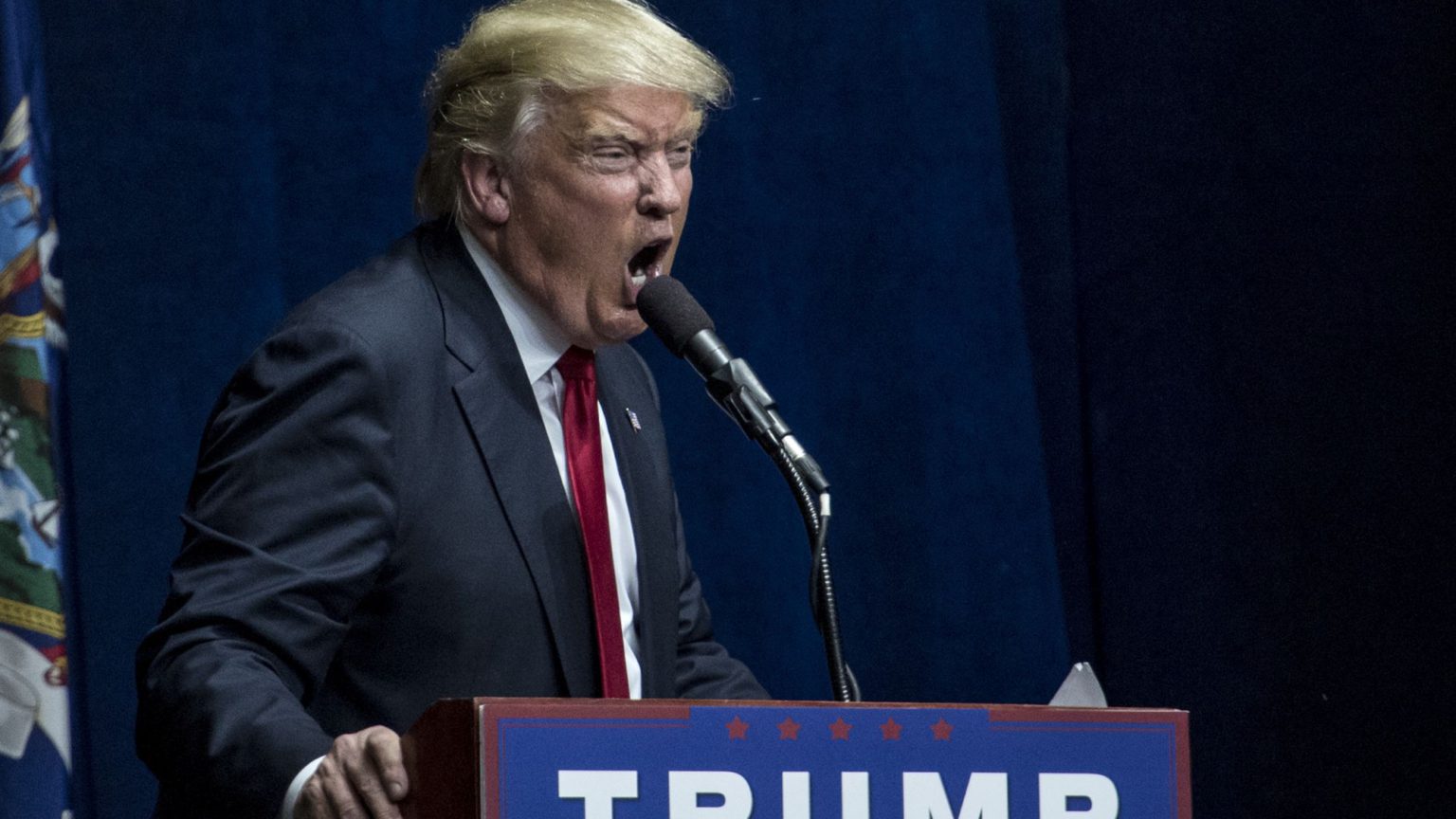

I have asked many Americans, in person and online, why they voted for or support(ed) Donald Trump. More than once I got nearly the exact same response: ‘Fuck you, that’s why.’ Because irritating me and who I represent, an educated elite that is both arrogant and aloof, is a good enough reason to cast a vote for the most powerful position in history. And it is irritating. For one, as a relatively conservative libertarian I am not the liberal monster they imagine – I simply can’t stand Trump, probably for many of the same reasons they support him. For another, I can’t help but feel an instinctual revulsion at this thought process; what do they get out of it? Honestly, what kind of childish oaf acts like this?

Then I remembered. Me.

You probably remembered, too. It’s likely that we have all acted with petulant disregard for the personal consequences of our actions as long as that asshole is hurt or at least inconvenienced or stymied. And there is no shortage of assholes. People who jump the queue, don’t clean up when their dog craps on the sidewalk, go out of their way to be rude, or don’t otherwise know how to be considerate homo sapiens, are everywhere. There are over seven billion people on the planet and, while the majority of people are not mean or selfish, there is still an unfortunate surplus of assholes.

And we usually want something to happen to assholes. Even ones we’ve never met. But what do we get out of it? How do we justify our petulance?

There is a type of structure colloquially known in the US as a ‘spite house’, a building designed with the specific intent of annoying someone else, usually family. The oldest known example in the US is 60 years older than the country itself, built in 1716 by one of a pair of squabbling brothers and designed to spoil his elder brother’s view. The building of spite houses is actually the plot of an Edgar Allen Poe short story, in which the central character constantly responds to a wealthy landowner planning a new building by buying adjacent property, and building an ugly house on it so the new wealthy neighbour will have to pay him to tear down the eyesore. Perhaps the best-known recent example is the ‘equality house’, painted a spectacularly bright LGBT rainbow pattern and neighbouring the home of the notoriously anti-gay Westboro Baptist Church. All these houses share two themes: they were built to annoy and the annoyance is worth more than they cost to build or live in.

Spite seems to be a universal human trait. history is replete with examples of spiteful actions from all over the world. Today spite houses can be found everywhere, from Argentina to China. The famous phrase about cutting off one’s nose to spite the face has origins in a story about a 9th-century Scottish nun.

Although frequently used as a synonym for revenge or aggression, spite differs fundamentally from simple retribution because it always carries a cost. Acting spitefully implies risk and expense. It’s not enough to hurt someone else; it’s wanting to hurt someone else in spite of the toll. Spite isn’t hating your ex; it’s hating them enough to spend time, money and effort to cause them financial, physical or emotional distress (a feature common to divorced couples the world over, from what I can tell).

Some researchers refer to spite as ‘the neglected ugly sister of altruism’, in that both require some sort of sacrifice, and that practitioners of both may be concerned with more long-term or at least less obvious benefits. Other scientists go so far as to suggest that spite is actually a manifestation of altruism itself, as any spiteful actions that negatively impact a particular individual or group necessarily benefits a competing individual or group. And emotional satisfaction qualifies as a benefit. Think of it as group-shared schadenfreude – the pleasure we get from watching someone get what’s coming to them, which we will gladly pay for.

In politics, what do we get out of voting against somebody instead of for something? Especially when it hurts us? Why did San Francisco risk severe water shortages for 884,000 people just to spite Donald Trump? Why is ‘owning the libs’ justification for wearing logos and symbols guaranteed to aggravate your fellow citizens, even when there’s a not insignificant chance it can lead to violence against you?

Evolutionary scientists suggest that such spiteful nonsense is beneficial for group cohesion and strength vis-à-vis that of their opponents. Other researchers propose an alternate, or possibly complementary, explanation for it: spite may encourage fairness. That is, spite is how we signal our displeasure with how society currently keeps score. It’s a way of saying the rulebook needs revision. In the meantime, the spiteful appear stronger because they ‘weakened’ their opponents – even if it’s by looking like an unhinged loon who doesn’t care about the personal cost. Or, as Frank Marlowe, a biological anthropologist at the University of Cambridge, puts it: ‘If you get the reputation as someone not to mess with and nobody messes with you going forward, then it was well worth the cost.’

A defining attribute of spite is disproportionality, a break in social norms. This supports the idea that spite is a way we demonstrate our dissatisfaction with those norms. It also helps explain why, ‘Because they want it’, is sufficient excuse to oppose whatever it is the other party is trying to do – actual reasons come later. We’re trying to force the system to readjust to what we want the new standards to be.

It doesn’t help that we exist in a media-driven morphine drip of spite. American media is structurally incentivised to deliver sensationalism and, practically by definition, spite is sensational. We want to watch the unusual and irreverent. Spiteful people are entertaining. Acts of spite, like spite houses or a governor vetoing a bill with a literal ‘fuck you’ letter, are usually amusing, if not straight-up hilarious. It’s good copy and TV was made for this.

Politicians have learned this too. Spite energises people. Getting in your adversary’s metaphorical face with nasty barbs and insults, loudly promising to fight against whatever the other guys are doing – no matter what, gets your base active and to the polls. Having a quick tongue on Twitter isn’t the worst way to promote your personal brand, as politicians as far apart as Donald Trump and Jeremy Corbyn know well. Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals’ fifth rule is ‘Ridicule is man’s most potent weapon. It is almost impossible to counterattack ridicule. It infuriates the opposition, who then react to your advantage.’ Spite can be tactical. Spite can be beneficial.

And who doesn’t like a good insult?

Thomas Brown is a recovering political consultant hiding in the American South. He is a history teacher and freelance writer. Argue with him on Twitter: @reallythistoo

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.