Long-read

After the Berlin Wall: whither democracy?

The democratic promise of 1989 is still far from being realised.

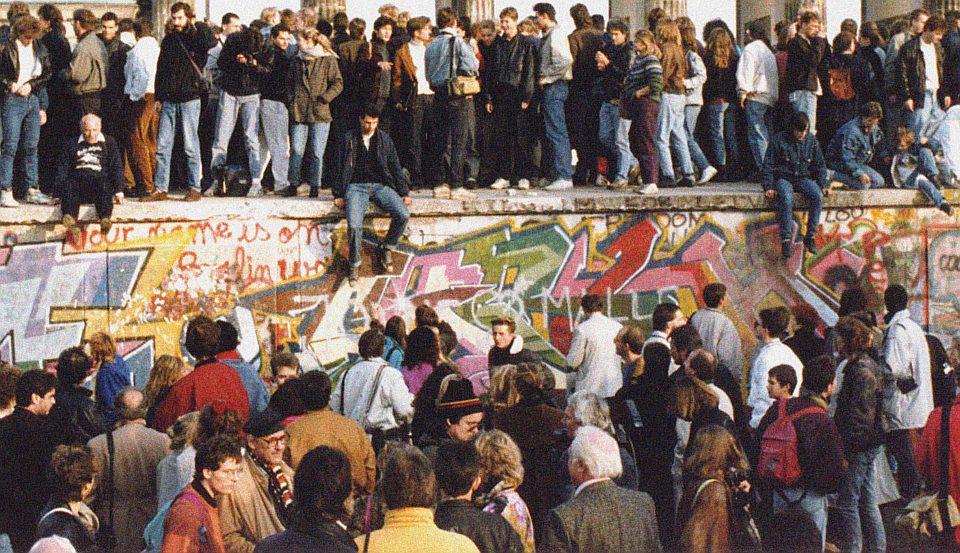

The fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989 symbolised not just the end of the Cold War and Stalinism, but also the triumph of the people of the former East.

In the weeks before the wall fell, hundreds of thousands took to the streets of East German towns and cities, demanding press freedom, the right to form political parties and hold free elections, and the reunification of Germany. Indeed, one of the most memorable demonstrations took place on 9 October in Leipzig, where 70,000 people defied government threats of violence.

The bravery of protesters throughout the German Democratic Republic (GDR) at that time cannot be understated. Only a few months earlier, the GDR’s rulers, the Socialist Unity Party, had expressed support for what was to become known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre in Beijing, China. There were even reports that East German hospitals were stockpiling blood ahead of the anticipated acts of state repression.

But the East German people were not to be deterred. On 9 November, reacting to the news that the GDR government was going to relax travel laws, thousands of people began flocking to the border checkpoints in Berlin, chanting ‘tor auf’ (‘open the gate’). At midnight, border guards, insecure and overwhelmed, gave way – a few hours later, some of the guards even started helping people to chip away at the hated wall that had divided Berlin for nearly 30 years. Over the course of the following three days, Berlin experienced ‘the greatest street party in the history of the world’. Capturing the mood and the hopes of the moment, Willy Brandt, West Berlin’s former mayor (and first Social Democratic Party (SPD) chancellor of West Germany) said, ‘Now what belongs together will grow together’.

Thirty years on, only the memory of that enthusiasm remains. ‘The anniversary falls into an overall climate, which, to put it mildly, is difficult’, said the SPD’s Matthias Platzek, head of the government commission for the preparation of the anniversary, recently. He spoke of ‘West German-bashing in the east and positive disinterest in the west’. A recent government report seems to support this, stating that 60 per cent of residents in the former East Germany regard themselves as second-class citizens. More than half of them said that reunification has failed.

Today’s conflicts might look as if they still devolve upon the old East-West divide. Underlying them, however, is a struggle over the meaning and legacy of 1989 and the reunification of Germany. That is why surveys seem so contradictory, expressing both satisfaction and disillusionment. Thomas Petersen, head of Germany’s famous Allensbach Institute, found that material differences between former East and West Germany are less significant now than ever before, and that the vast majority of Germans consider the events of November 1989 a ‘source of great joy’.

If there are problems between Germany’s east and west today, then, they are political. And therefore the German government’s plans to organise ‘citizens’ dialogues’, at which people from east and west Germany can come together to discuss the ‘achievements, failures, successes and injuries’ of the past 30 years, look likely to miss the mark.

The struggle over the meaning of the post-1989 era is most clearly played out through the rise of populism. The Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party has led three successful election campaigns in the former East German states of Brandenburg and Saxony (in September 2019) and Thuringia (October 2019), using the slogan, ‘Vollende die Wende’ (‘complete reunification’). The slogan was widely criticised in the media. ‘People are told to go back on to the streets, like they did in 1989, and bring the system down’, said one journalist on a programme entitled How the AfD has appropriated reunification. Elsewhere, an open letter, written by a group of former GDR civil-rights activists, accused the AfD of ‘historical lies’. But the AfD can also point to several former dissidents who sympathise with it. And so the battle over the meaning of 1989, which is simultaneously about today’s politics, is set to continue.

At the centre of the stand-off between populists and anti-populists is the question of what values people were fighting for 30 years ago. In an essay for the New York Review of Books, Timothy Garton Ash speaks of a ‘wave of anti-liberal populism where 30 years ago there was a liberal revolution’. The West’s mistake after 1989, argues Garton Ash, was to imagine that liberal, Western values were to be the global norm. He thinks it led to a form of complacency.

Populists such as the AfD are not the heirs of the spirit of 1989, Garton Ash continues. That mantle now falls, he argues, to the anti-populists leading the protests against the ‘socially conservative backlash’. Describing an anti-populist demonstration in Prague, Garton Ash writes of a ‘sea of citizens, enthusiastically waving the yellow-and-blue flag of the European Union… Stirring stuff.’

Yet much of what Garton Ash thinks represents Western values, from the right to abortion to gay rights, has little or nothing to do with the motives and wishes of the East German protesters of the 1980s. Homosexuality was not illegal in the GDR, and abortion was widely available.

Opposition to reunification ranged from West German Social Democrats and Greens, to many West European heads of state

And it is not just the AfD that has been trying to appropriate the legacy of 1989, and use it to promote its own agenda – which, as Garton Ash rightly says, is often accompanied by xenophobic rhetoric. Others, on the opposite side of the political spectrum, have been doing this, too. ‘Three decades ago, we celebrated the fall of the Berlin Wall’, writes Jan Zielonka, a professor of European Politics at the University of Oxford. ‘It was the mother of all walls… Today, walls are back in vogue around the world… An ever larger part of the electorate supports politicians calling for the restoration of sovereign nation states.’

Yet the 1980s protesters didn’t want to abolish sovereign nation state or borders. On the contrary, they were motivated by a desire to regain national sovereignty from the Soviet Union. This is why all the protest movements throughout the Eastern Bloc took on specific national forms. When Polish workers at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk went on strike in 1980, in the first signs of the anti-Soviet revolt to come, the red-and-white Polish flag could be seen everywhere. Even the logo of the Solidarność (Solidarity) trade-union movement, featuring red script on a white background, alluded to the Polish flag.

In East Germany, the national question was also present from the start. The GDR was a satellite of the Soviet Union and reliant on credit from West Germany. But it had always tried hard to cut its historical and cultural links to the West. So while the Federal Republic considered every person coming from the East as a German citizen, the GDR demanded visas from West Germans. It also insisted that its name was the German Democratic Republic, and not East Germany. Often to their amusement, visitors to the eastern part of Berlin would be informed that they were entering ‘Berlin, the capital of the GDR’.

It is true that the first banners demanding reunification only appeared after the wall fell, and the GDR had all but collapsed. But that was because of the great dangers involved in demanding reunification in the GDR while it still existed. Hence the original protest slogan was ‘Wir sind das Volk’ (‘We are the people), which was directed at the GDR’s Stalinist government. But from mid-November onwards, it changed to ‘Wir sind ein Volk’ (‘We are one people’), which was directed at the establishment in the West. Soon calls for reunification became so powerful that they could no longer be ignored.

In calling for reunification, people were demanding rights that had been withheld for decades. These included an end to the command economy, with all its hardships, and above all, democracy. When the first free elections were held in March 1990, an impressive 93.4 per cent of the population in the old East took part – which remains the highest ever turnout in any free election in Germany. East Germans didn’t need to be convinced of the virtues of civil liberty and democracy. That’s because, as political scientist Robert Rohrschneider put it in 1999, they knew what it meant to live in an authoritarian system (1).

One of the most amazing aspects of 1989 was that, across Europe, few in power expected it. ‘Of course we said that we believed in reunification, because we knew that it would never happen’, said former UK prime minister Edward Heath in 1989. When reunification did appear on the popular agenda, it became apparent how large and diverse the opposition to it was. It included the most unlikely of allies, from prominent former East German civil-rights activists (2) and the West German SPD and Green Party, to many Western European heads of state.

Several former East German dissidents, like Bärbel Bohley, campaigned for reform of the GDR system. She and others identified with the environmentalist and anti-consumerist rhetoric of the West German Green Party, which was very successful during the 1980s. The Greens, like large sections of the West German Social Democrats and others, identified with Stalinism more than they liked to admit. They were turned off by the sight of so many people demanding democracy and an end to the command economy. So they became supporters of the status quo. ‘We were anti-nationalists’, explained former Green Party leader Ralf Fücks in 2015.

Both the Greens and the SPD were soundly beaten in the 1990 federal election. Indeed, the Greens won a meagre 3.8 per cent of the vote with their bizarre anti-nationalist slogan: ‘Everyone is talking about Germany. We are talking about the weather.’

Helmut Kohl, West Germany’s conservative chancellor, became the man of the moment. He understood that reunification was the only way forward. ‘The proletariat rushed into the streets, not knowing what it would find. And it found Herr Kohl’, wrote the American author Ward Just in his novel, The Translator.

Outside of Germany, the speed and turn of events also prompted apprehension. On 28 November, Kohl presented his ’10-point programme for the formation of a contractual community’ (effectively, a plan for German reunification). The then British prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, who had made no secret of her hostility to reunification, quickly demanded that any talk of a united Germany should be postponed for at least five to 10 years (3). French president François Mitterrand informed a group of journalists that he considered German reunification a ‘legal and political impossibility’. A reunited Germany ‘as an independent, uncontrolled power was unbearable for Europe’, he concluded.

With Western Europe’s most powerful states opposed to reunification, Kohl’s most reliable ally became US president George HW Bush. As journalist Elizabeth Pond wrote, the US played a decisive role in reversing the resistance of the British and French. There was, however, one condition placed on German reunification – it was to take place within the European Community.

Kohl, who had already modelled himself as a ‘European chancellor’ in the mid-1980s, was not averse to German reunification taking place within the structures of the European Community. Thus the process of reunification fused with plans for the European Union, culminating in the signing of the Maastricht Treaty in February 1992. The most far-reaching part of Maastricht – and the most contested within Germany itself – was the decision to create a monetary union, with a common currency, namely, the Euro. According to historians Andreas Rödder and Heinrich August Winkler, Kohl accepted that a reunified Germany would have to enter a monetary union in order to win support for reunification from France. It was a concession that came at a price for the French, too. It meant the French state was also to be bound to the fiscal rules and regulations of the EU. As French political scientist Anne-Marie Le Goannec explains in L’Allemagne Après la Guerre Froide, it was France’s admiration for the ‘German Model’ that helped Kohl push through the fiscal rules of the EU. Maastricht, however, was unpopular from the start. And in a referendum held in France in September 1992, only 50.8 per cent voted in favour of it.

By 1996, German support for the EU had dropped to 35 per cent in the east and 40 per cent in the west

Maastricht was also unpopular in Germany. Unlike the French electorate, however, the German electorate was never consulted. The absence of any public vote was compounded by the weakness of the opposition SPD, which had never recovered from its position on reunification. It meant that Kohl’s government was given a free hand to reunify Germany as a part of the European Union.

Eurobarometer polls indicated just how unpopular Maastricht, and all that it entailed, was. Admittedly, support for a united Europe had been high in the early 1990s, especially in the former GDR, where over 85 per cent were in favour, compared with 70 per cent in the former West. By 1996, however, support had dropped to 35 per cent in the east and 40 per cent in the west (4). Christopher J Andersen, a professor of political science at New York State University, attributes the sharp drop-off in enthusiasm for the EU to the job losses and economic problems that plagued the former East German economy (5).

Germany’s current problems, which have overshadowed the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, cannot be reduced to a single cause. But the realisation that the democracy offered in the West was constrained and limited has certainly played a crucial role in fostering a feeling of disappointment. As Kohl admitted in an interview in 2002: ‘I acted like a dictator when the Euro was introduced.’

It wasn’t just the abolition of the well-loved Deutsche Mark, pushed through by Kohl, which annoyed so many Germans. Other deeply unpopular policy measures, which would probably have been rejected by the electorate, if they’d ever been asked, included: the expansion of the EU; the free movement of cheap labour from impoverished eastern Europe (leading to wage depression); the German military intervention in the Yugoslav war; the handling of the Greek debt crisis; and the temporary loss of control over borders. Again and again the structures of the EU have allowed different German governments to ignore the opinions of the electorate and pursue unpopular policies.

On 3 October 2019, as Germans were celebrating the 29th anniversary of the official reunification, the European Commission tweeted, ‘Happy German Unity Day!… 16million GDR citizens joined the European Community on 3 October 1990.’ But 30 years ago the German people were not fighting to join the EU. They were fighting for democracy and civil liberties. It was a brave fight for freedom that, contrary to the Commission, did not end 29 years ago. In fact, it is still going on today.

Sabine Beppler-Spahl’s Brexit – Demokratischer Aufbruch in Großbritannien is out now.

(1) ‘Learning Democracy: Democratic and Economic Values in Unified Germany’, by Robert Rohrschneider, in The Federal Republic of Germany at Fifty, edited by Peter H. Merkl, Palgrave Macmillan, 1999, p81

(2) Deutschland einig Vaterland, by Andreas Rödder, CH Beck, 2009, p66

(3) Deutschland einig Vaterland, by Andreas Rödder, CH Beck, 2009, p235

(4) ‘Public Opinion and European Integration’, by Christopher J Anderson, in The Federal Republic of Germany at Fifty, edited by Peter H. Merkl, Palgrave Macmillan, 1999, p321

(5) ‘Public Opinion and European Integration’, by Christopher J Anderson, in The Federal Republic of Germany at Fifty, edited by Peter H. Merkl, Palgrave Macmillan, 1999, p323

Headline picture by: PA Images.

In-article pictures by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.