‘People should pursue mind-enhancing pleasures’

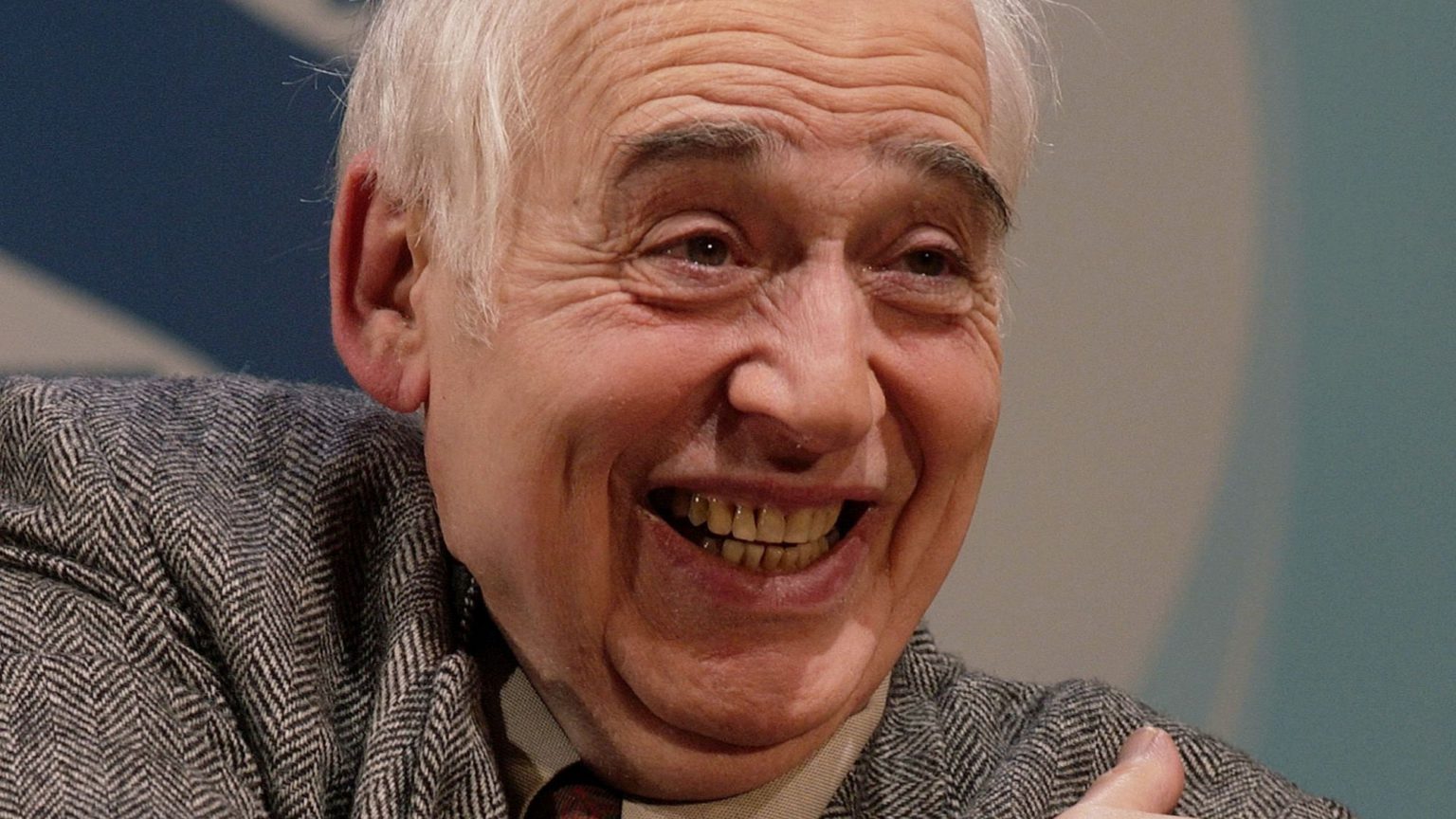

In one of his last ever interviews, Harold Bloom talks about the vital importance of reading and thinking.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Earlier this year, what was to be the late Harold Bloom’s final book was published. Possessed By Memory: The Inward Light of Criticism is different from his other works. It is more personal, somehow. And certainly more elegiac. But it is familiar, too. He converses with great works of literature as if their authors are still present. And he still writes as if what he’s doing matters, perhaps more than ever.

To find out more about Bloom’s literary mission, the importance of the canon, and why we need to read better, spiked spoke to him at the beginning of the summer. Here is what he had to say in one of his last ever interviews:

spiked: Why did you write Possessed By Memory?

Harold Bloom: I have to go a long way back. In a very little time, on 11 July, I turn 89. I will be beginning my 65th consecutive year of teaching at Yale at the end of August. I’ve written some – I can’t even count any more – maybe some 55 books. It depends how you count.

But essentially, I’m a schoolteacher. For me, reading, writing and teaching are one activity. And essentially, my career, whatever it comes to, has been an attempt to preserve a deep need for the reality of high literature other than ephemeral literature or journalism or politics. So I’ve now reached a point where, having always been an experiential critic, I’m more and more inclined to go inward. And the book Possessed By Memory is a kind of reader’s memoir.

Oscar Wilde said that criticism is the only civilised form of autobiography. And in that sense, Possessed By Memory is an attempt to sum up maybe not all but a good deal of my previous work. I see it as a kind of spiritual and literary memoir of the self while avoiding any of the mere incidents or accidents or usual losses of life.

But also, if you’re 89, you face the sadness that the great poets and the fellow critics are almost all departed. So the book is also a kind of elegy for my departed friends – poets like John Ashbery and Richard Wilbur, Archie Ammons and Mark Strand. And also for the scholar critics I was most associated with who are now gone. Angus Fletcher, Geoffrey Hartman and Richard Rorty, who is also a very special kind of philosopher. And in a sense also for the various sages I know: Gershom Scholem, a great; Robert Penn Warren a very dear friend, a very wise man, and at his best a very powerful novelist and poet. And of my own mentors who have gone – MH Abrams, Frederick A Pottle, William Wimsatt, and others. The people who taught me.

It’s not a lament. I think I remark somewhere in the book – if I didn’t I should have – that I think I’m most moved by the fact that I get endless visits, email and hard mail from people I have never met and will never meet unless they do come on a visit, who tell me I’ve been their teacher. And it makes me very happy because that’s why I write books – I write books as an act of teaching.

There’s nothing better for our fellow human beings that anyone can do than be a schoolteacher. Even if our foul society, our ghastly regime – though I don’t wish to get into politics – doesn’t properly honour schoolteachers. Because it’s the teachers out there, in the primary schools and the junior high schools and high schools, to some extent in the charter schools, in the junior colleges – it is those people who are doing the hard work of trying to maintain literacy.

spiked: Reading about your life-long intercourse with long-dead writers and poets, I was reminded of Machiavelli in the The Prince, where he writes of his relationship with the Ancients: ‘At the door [of my house] I take off my clothes of the day, covered with mud and mire, and I put on my regal and courtly garments; and decently reclothed, I enter the ancient courts of ancient men, where, received by them lovingly, I feed on the food that alone is mine and that I was born for. There I am not ashamed to speak with them and to ask them the reason for their actions; and they in their humanity reply to me.’ Did you feel something similar when thinking about writing Possessed By Memory?

Bloom: Yes, but the difference is that I was and am haunted by the ghosts of my departed friends, most of them poets and critics.

spiked: What kind of book is Possessed By Memory?

Bloom: Possessed By Memory, even though it is a work of literary criticism, isn’t really that. There is nothing difficult about it – I have written difficult books, almost recondite books, like The Anxiety of Influence or Kabbalah and Criticism or A Map of Misreading. This is a very open book. It goes back to the Bible and talks about Biblical stories. It goes through Shakespeare again, but on the ground level, trying to make his work even clearer. It goes through the poems I have loved best and longest, and have taught the most, and that I keep reciting to myself at night. And it gives a reading of the only novelist I think can rival Shakespeare – Marcel Proust – by giving a very careful and I hope clear account of the great novel In Search Of Lost Time.

spiked: There continues to be a lot of debate today about the canon, and literary tradition in general – that they’re too white, or too prescriptive. Do you think we’re losing a sense of literary value?

Bloom: The great problem in our society is the exaltation of pop culture – that anything goes. And the whole scale of measurements, the whole scale of value, has been diminished and even demolished.

My mission as a teacher and a writer is to try to get people to stop satisfying themselves with lesser stuff and to look at more difficult and more rewarding and more mind-enhancing pleasures like reading Shakespeare or Cervantes or Proust or James Joyce. That is to say, something that teaches you how to think. If you don’t know how to read properly, and if you do not read or absorb the best that has been thought and said, then you will never learn to think properly. And if you don’t know how to think properly, then you get the disaster of our current society. We could not have this monstrous, evil, mindless president and this horrible debasement of all our humane values if people were properly educated.

spiked: You at times speak quite frankly about death. How has Possessed By Memory helped shape your relationship to mortality? Was it supposed to?

Bloom: I did not intend to reflect on my own mortality. Less than two months away from turning 89 I am always in the elegy season. Freud was a good guide when he told us to make friends with our own mortality.

Harold Bloom was talking to Ella Whelan

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.