Long-read

The People’s Republic of China at 70

It has overcome a fraught past to emerge as a world power – but there are clouds ahead.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

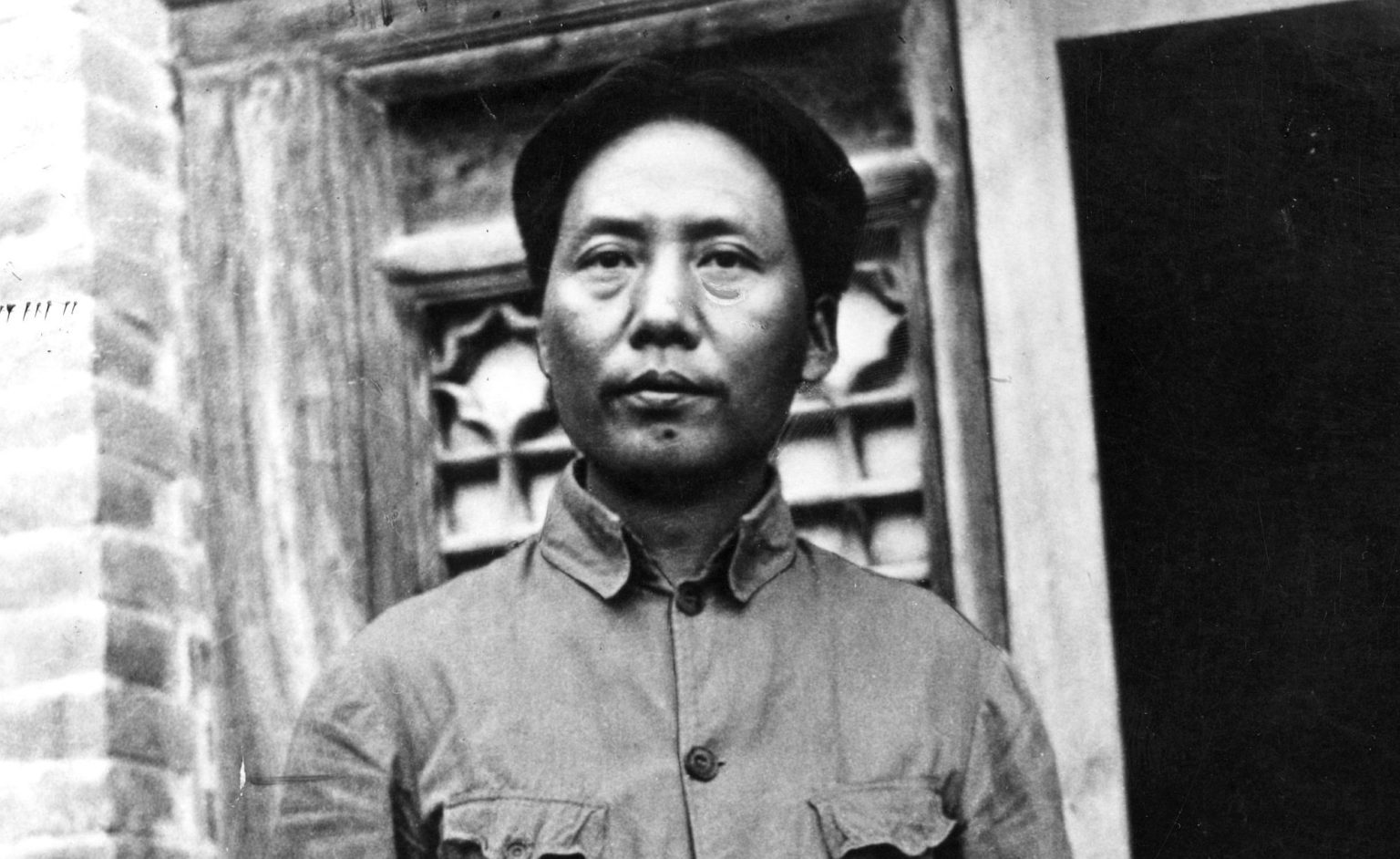

The People’s Republic of China was founded on 1 October 1949 with an address by Mao Zedong, Chairman of the Communist Party. Speaking from the Gate of Heavenly Peace (Tiananmen) in front of the Imperial Palace in Beijing, he announced victory over Chiang Kai-shek’s Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, or KMT) and its military wing. He laid claim to a new nation run by and for the Chinese people. China had finally reached a peaceful resolution to almost 18 years of war and civil conflict. It was time to build a new republic.

For the Chinese, the Second World War – known as the Second Sino-Japanese War – had begun in 1931 with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. By 1937, Beijing and Tianjin had been lost and the barbaric assault on Nanjing was just beginning. By 1945, while the rest of the world celebrated the peace, China was mourning the deaths of 15million people, including around 12million civilians, and sinking into another round of internecine struggle between Nationalists and Republicans.

This civil war was a continuation of the internal power struggle that had begun in the 1920s. It continued even while China was conducting the war against the Japanese, and would last until 1949. It is estimated to have cost the lives of one million soldiers and five million civilians (1945-49).

These are the painful origins of National Day in China – a public holiday celebrated on 1 October every year. Little wonder that on that inaugural National Day in 1949, British journalist Christopher Dobson observed a tired, bedraggled nation. ‘Mao’s guerrilla fighters shambled past’, he wrote of that first parade, ‘and his Mongolian cavalry jogged along on their half-wild ponies’.

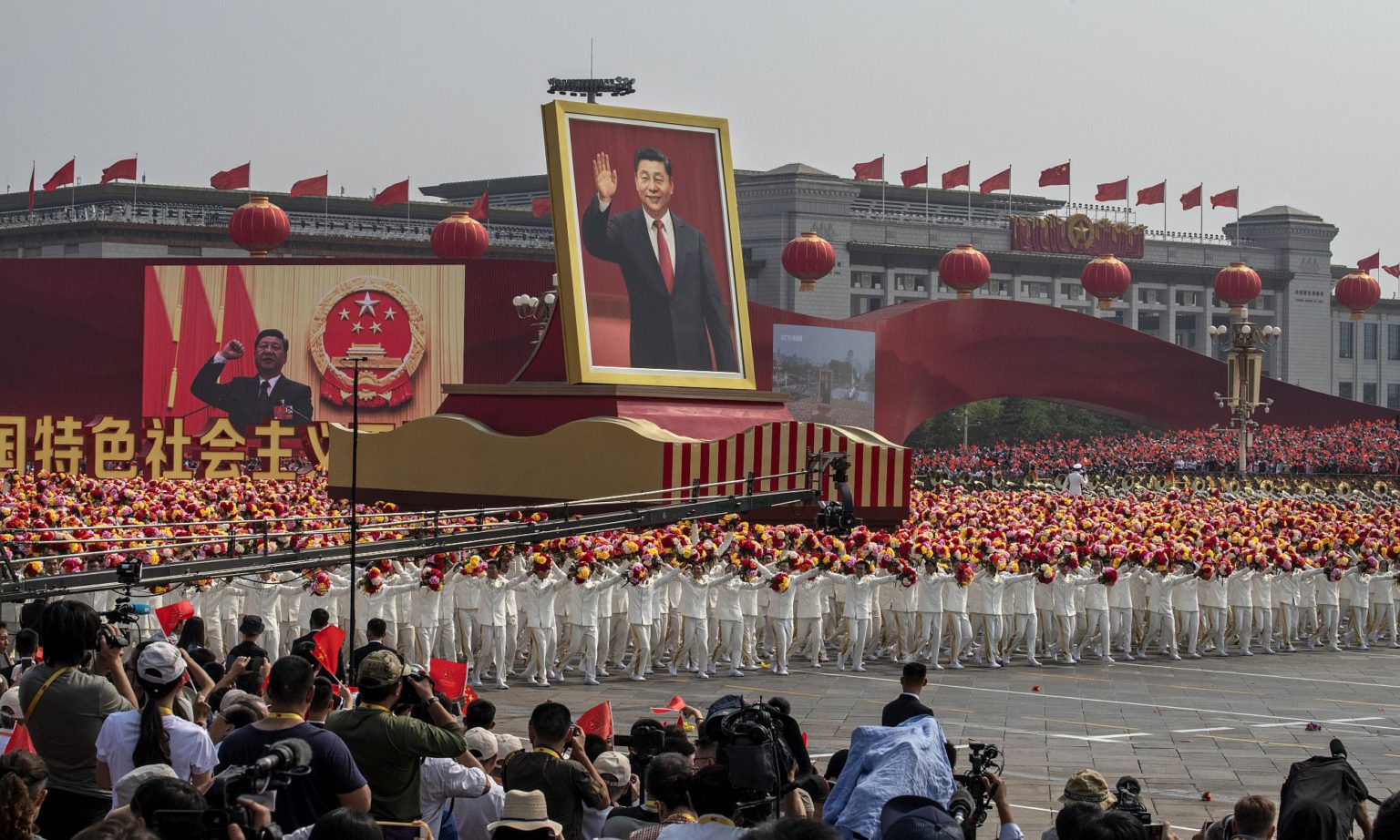

In marked contrast, on National Day 70 years later, President Xi Jinping presided over a display of some of the most advanced military hardware in the world. He boasted that ‘no force can shake the status of this great nation’. In addition to the 15,000 troops on show, there were stealth drones, tanks and military aircraft, while pride of place was given to the nuclear Dongfeng (eastern wind) intercontinental ballistic missile, which military analysts say can hit the US within 30 minutes.

This is a far cry from 1 October 1949, when the military budget was so low that Chinese fighter pilots were instructed to circle round before flying past again, to fool the audience into thinking that the People’s Republic had more fighter planes than it really did. Even in 1990, China’s military budget was a mere $10 billion a year. Today it is $250 billion.

China’s rise has been unprecedented, especially given the almost unimaginable horrors endured by its people in the course of its modern history. Historian and critic Frank Dikötter calculates that the Communist campaign to change China from a predominantly agrarian society to a modern, industrial one, known as the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962), resulted in 45million Chinese people being ‘worked, starved or beaten to death’. This was followed by the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), Mao’s attempt to purge and ‘purify’ Chinese society. It resulted in millions being forcibly sent into the countryside to live with the peasants, and hundreds of thousands more being tortured, killed and enslaved. Modern Chinese history is replete with such horrors. So it is hardly surprising that China’s recent emergence as a world power, a productive economy, a consumer-goods producer, and a stable society has been embraced by a grateful population.

Reckoning with China’s past

Dikötter is a major thorn in the side of apologists for the Chinese Communist Party. His three magnificent volumes on the history of the People’s Republic provide a devastating account of the various periods of Mao’s reign and the consequences of his agrarian policy. But relentlessly exposing and criticising Mao’s brutality should not come at the expense of understanding the historical conditions that gave rise to it. As with Robert Service, in his history of Stalinist Russia, Dikötter’s generalised dislike of Communism impairs his objectivity. His approach is, as one critic puts it, ‘relentlessly partial’.

At least he does not try to hide his partiality. In a recent article, Dikötter reviews the evidence and states that the emergence of the Peoples’ Republic in 1949 ‘was a liberation that plunged the country into decades of Maoist cruelty and chaos… [A]n initial Great Terror claimed some two million lives between 1949 and 1952.’

The horror and magnitude of the slaughter is real enough, of course. But was it caused by liberation, as Dikötter has it? To think it was, as Dikötter suggests, is a way of arguing that China’s modern past would not have been quite so gruesome if Mao had not intervened, as if it was the challenge to the status quo that was the problem. Dikötter even suggests that life in China was better before the foundation of the republic.

For some it was. The upper strata of Chinese society did enjoy an affluent, even decadent lifestyle, in the bars and dancehalls of 1920s and 1930s Shanghai – it wasn’t known as the Paris of the East for nothing.

But for most people, there was a desperate need to transform Chinese society radically. In 1919, pro-democracy advocates were fighting for sovereign rights after the Great Powers had carved up the nation at the Versailles Peace conference. The Chinese Communist Party, founded in 1921, developed as a response to the chaos of a fragmented society and was influenced by the transformational possibilities promised by the Russian Revolution.

By 1927, Communist members numbered more than 60,000. With growing unrest, the anti-communist Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek commenced a bloody purge, targeting not just Communists, but also troublesome workers and trade unionists. Thousands were slaughtered in the streets of Shanghai. The following year, Nationalist forces mounted a campaign of suppression across China.

But the genie was out of the bottle. The radical fervour unleashed during the 1920s delivered a hammer blow to the remnants of traditional authority in China. Then, with Japan having invaded Manchuria in 1931, China was dragged into a war it didn’t want.

The use and abuse of China

As China historian Rana Mitter writes, China’s frontline was largely ignored and unaided (some say, sacrificed) by the West throughout the war years. But there is little doubt China formed an invaluable bridgehead in the fight against fascism globally (1).

It was a brutalising fight, too. In 1941, the Japanese invaders pursued a policy known colloquially as the ‘three-alls’ – ‘kill all, burn all, loot all’. But then, these were inhuman times. Remember, the war was ended by America dropping atomic bombs on Japan – with UK Labour government acquiescence (2) – an act that destroyed around 100,000 lives instantaneously.

The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, China’s war with Japan, and the still raging civil war between Republicans and Nationalists, created appalling conditions for the flowering of a new society. Mitter writes that ‘one of the great lost opportunities of the war was the loss of [China’s] tentative move towards pluralism’, because the post-war battles generated ‘a different path to the same goal: a modern, nationalist Chinese state’ (3).

Mao’s role in forging this bloody, dangerous path should not be downplayed, of course. His contingent relationship to modernity, his anti-urbanism, his pro-peasantry, pro-Stalinist approach to development – all of this was a disaster for China’s development. As a result, Mao has rightly been added to the pantheon of 20th-century Communist pariahs.

But Mao is also a little too convenient a hate figure. Western commentators regularly exhume him in order to feed the narrative that overthrowing the status quo, no matter how wretched it is, inevitably leads to, if not the gulag, then at least somewhere very bad. It is a scare story that clearly has a contemporary resonance. This school of thought fears and ridicules social change, believing that it will automatically lead to a worse state of affairs. It is better, therefore, not to rock the boat. This faux-historical narrative does not really tell us much about Communist China. Rather, China is simply being used as a prism through which the West can project and justify its own trepidation about the future.

‘Man must conquer nature’

Likewise, Western environmentalist criticism of modern China tells us more about the West than it does about China. Ironically, there is ostensibly much in Mao’s thinking that echoes in contemporary Western environmentalism. The Malthusian sub-text of Western environmental criticism of China, for example, is similar in spirit, if not in implementation, to the anti-modernist and pro-pastoralist thinking of Mao. So while Mao sent millions to the countryside to learn from the peasantry, so that they might ‘develop their talents to the full’, as Mao put it in 1955, so contemporary environmentalism speaks of the intrinsic moral worth of a close connection to nature. And while Mao argued that ‘all people who have had some education ought to be very happy to work in the countryside if they get the chance’, so today’s environmentalist, off-grid movement might well endorse a similar sentiment (4).

But the parallels with environmentalism are misleading. Mao’s 1945 dictum ‘Man must conquer nature’ was intended as a rallying cry against what was hitherto deemed the natural order: against the imperious reality of foreign rule; against China’s deference to world powers; and against subservience to natural forces. China’s leadership was prepared to do what so many contemporary Western leftists are not: take a risk, and radically overhaul the status quo.

There are too many today who use China’s fraught past to condemn its present. As Judith Shapiro argues in Mao’s War Against Nature (2001), the parlous state of much of China’s environment is too often presented as the result of the rapid growth of the Chinese economy over the past four decades since Mao’s death. This is a convenient argument for those nations for which a slowdown in China’s economic growth would benefit their own competitiveness. For example, the closure of China’s state-subsidised steelworks cannot come too soon for other nations’ steel industries.

The capitalist turn

After Mao’s death in 1976, there was a possibility for another break with convention. After a brief interregnum, overseen by now forgotten premier Hua Guofeng, the incoming premier Deng Xiaoping broke with Mao’s legacy and proposed meagre but nevertheless significant capitalist reforms. This was the kind of change very much welcomed in the West – namely, a turn towards capitalist production and exchange. For years, peasants had been forming unofficial, illegal markets to exchange their paltry surplus products in order to make ends meet. But Deng’s Town and Village Enterprises initiative, launched in the early 1980s, allowed collective enterprises to set up shop legitimately, and produce and sell surplus goods openly. Deng also experimented with four special economic zones (SEZ) in 1980: Shenzhen, Guangdong, Zhuhai and Xiamen. These were protected economies with internal market freedoms.

In many ways, such policies had been the downfall of the Soviet Union under reformist president Mikhail Gorbachev. So the Chinese Communists were understandably nervous about economic liberalisation. In order to protect itself, then, the Communist state continued to push ahead with economic reform, but it did so while monitoring the minutiae of everyday life. And ever since, Western powers have waited for China finally to come over to the side of commonsense, Western-style liberal democracy. And every year, they have been disappointed.

Deng was always aware of the risks entailed by economic reform. First he made sure that the early market-oriented experiments were on the south China coast, far enough away from the Communists’ seat of power in Beijing that capitalist ideas would not contaminate the party. And secondly, of course, these experiments were strictly managed and regulated, complete with rigidly enforced penalties.

Deng’s 1992 ‘Southern Tour’, in which he travelled through Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai and Shanghai, drumming up support for marketisation, consolidated his reputation as the chief architect of China’s reformist Opening Up programme. He was portrayed as the pragmatic liberal, the social reformer. It meant that Deng’s reputation, aided by the strict media controls in place, survived the callous one-child policy launched in 1980, and the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989.

In 1995, a Western academic pointed out that ‘while Chinese leaders express commitment to economic liberalisation, there are also authoritative calls for rolling back the reforms and reimplementing plans and controls’ (3). By this point, six years after the Tiananmen Square massacre, the Communist Party had already consolidated its authority, ousted political opponents, and began the next phase in China’s monumental rise. The contradictions inherent in Chinese Communist rule were well documented even then, but China always lived to fight another day.

But is it all – finally – going wrong? Current president Xi Jinping has definitely turned the clock back on liberalisation, and there is a sense of foreboding in the air. Official misdemeanours, local protests, policy challenges, Western interference and illegal activity, are all being clamped down on with greater speed and severity than they have been for a long time. China has never been a liberal democracy, but the escalating persecution of minority groups, the surge in arrests and deportations of foreigners, increased surveillance, temporary detentions and increasing censorship reveal the extent and depth of the Communist Party’s siege mentality. For all its displays of military might, China is getting jumpy, and the unrest in Hong Kong is not helping.

The trade war with the US is another problem. Although some regional players benefit from new trade opportunities with China, its relations with others are proving more fractious. At the moment Vietnam gains from China’s troubles, as more direct foreign investment flows in from those companies looking for stable investment opportunities in the region and seeking to avoid punitive tariffs.

Elsewhere, Japan and South Korea are entering a hostile trade war of their own; Hong Kong is on the brink of something, although no one seems to know what; and there are upcoming elections in Taiwan, which threaten to resurrect the old Chinese Nationalist-Republican battles of the 20th century.

Indeed, the Cold War’s eastern front in the 1940s was informed by the Soviet Union’s support for Mao’s peasant army, against the US-supported KMT. When the US withdrew its support for the KMT and its leader Chiang Kai-shek, they fled, battered and bitter, to Formosa island (present-day Taiwan) to form the Republic of China, which declared itself the rightful heir to China’s national government. Today, the friction between China and Taiwan is greater than it has been for a long time. In January 2020, Taiwan’s presidential election will pit the island’s pro-Chinese faction against West-supporting factions once again.

In the South China Morning Post, commentator Cary Huang writes: ‘The presidential race offers choices that divide the electorate along multiple lines – idealism or reality, confrontation or compromise, politics or economics. They pit mainland migrants against Taiwan natives, the old against the young, among the island’s 23million people.’ It is here that the next twists and turn of the region – and beyond – will be played out. With regional and global tensions rising, the question is: will it be America or China or even the EU which emerges as the peacemaker and powerbroker? Watch this space.

Austin Williams is director of the Future Cities Project. Follow him on Twitter: @Future_Cities

He will be chairing the debate ‘Hong Kong: Understanding The Protests’, at the Battle of Ideas, at the Barbican, Saturday 2 November, 14:00–15:30. For further details and to buy tickets, visit here.

Pictures by: Getty Images.

(1) China’s War with Japan 1937-1945, by Rana Mitter, Allen Lane, 2013

(2) ‘Labour and the Bomb: The First 80 Years, International Affairs’, by Len Scott, Royal Institute of International Affairs, Vol 82, No4, pp 685-700

(3) China’s War with Japan 1937-1945, by Rana Mitter, Allen Lane, 2013

(4) ‘The new environmentalism of everyday life: Sustainability, material flows and movements’, by David Schlosberg and Romand Coles, in Review of Contemporary Political Theory 15, p160

(5) The Beijing rule: contradictions, ambiguities and controls’, by J Frankenstein, in Long Range Plannning 28(1), 1995, pp 70-80

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.