The EU is holding back innovation

Its plans for innovation have precious little to do with science and technology.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Few noticed when Ursula von der Leyen, European Commission president-elect, nominated Bulgaria’s Mariya Gabriel as the EU’s new commissioner for what once was the Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (RI). Yet even fewer noticed that von der Leyen had stripped the old Directorate of its ‘Research’ tag, renaming it the Directorate of Innovation and Youth.

This coupling of innovation with youth doesn’t just reflect the education tasks that the new directorate is taking on, from tripling the Erasmus+ programme of EU student exchanges to building transnational alliances in EU higher education that promote ‘European values and identity’. No, it also shows that the new Innovation and Youth Directorate is less interested in advancing basic scientific research than it is in promoting PC lifestyles, especially youthful green lifestyles, as the key to innovation.

In a letter to Gabriel, von der Leyen highlights the EU’s two traditional, narrow yet fuzzy goals for innovation – ‘a climate-neutral economy and new digital age’. But she also charges Gabriel with preserving the EU’s cultural heritage, promoting creative industries, and promoting ‘sport as a tool for inclusion and wellbeing’.

So first the EU limits technological innovation to matters

Green and electronic. Then it blurs the whole concept of innovation, moving it away from science and technology and into the domain of culture. She is replacing real engineering with social and political engineering – above all among young people.

There are few surprises here. In December 2018, a management plan for the old RI Directorate promised to decarbonise energy and transport, and prove the economic and environmental feasibility of ‘the circular economy approach’ to resource use. Significantly, though, it also wanted Horizon Europe, the EU’s €94.1 billion programme of research for the years 2021-27, to go into ‘mainstreaming’ something called citizen science – what the EU elsewhere defines as the ‘non-professional involvement of volunteers in the scientific process’.

These are weasel words. In its plan, the EU concedes that it remained far from its target of spending three per cent of GDP on research and development. Yet its plan, and others since, has no ambitions for investment in and development of important new technologies, such as small modular nuclear reactors, or gene-edited crops. What it planned, rather, was to recruit amateur scientists to try to make credible the EU’s cramped yet blurred conceptions of innovation.

As an example of just how blurred the EU’s concept of innovation is, take urban innovation, the subject of €3.1 billion in EU investments. A March 2019 RI paper on the subject didn’t just uphold, as innovation, homegrown food and buying locally. It also praised the green lifestyle choices of ‘sustainability pacesetters’ – food, clothing and energy cooperatives, repair cafés, and eco-villages. The lifestyles of sustainability ‘pioneers’, it argued, ‘could inspire regional actors to make the changes needed to become sustainable, green economies’.

Beneath the EU-speak, the blueprint is clear. As the Council of the EU’s April 2019 prospectus for Horizon Europe confirms, Brussels subordinates scientific research to the United Nations sustainable development goals and the Paris Agreement on climate change. Hence Horizon Europe innovation, we are told, must be ‘responsible’ and follow the precautionary principle.

Mariana Mazzucato is Brussels’ favourite guru on innovation. Her July 2019 report, Governing Missions in the European Union, confirms the limited, cynically environmentalist nature of EU innovation policy. She writes: ‘Today there is a growing green movement – including the youngest school children – bringing the climate emergency right to the top of public priorities. We must harness this drive for change.’

Further on, she writes: ‘Rather than focusing on purely technological problems, we can focus innovation efforts to solve societal challenges that involve technological change, institutional and behavioural change and regulatory change.’

‘Rather than focusing on purely technological problems…’. It’s a telling phrase in a paper about innovation. And it’s one in the spirit of which the EU seems to have acted, given four out of its five innovation missions focus on green issues: ‘Climate change, healthy oceans, climate-neutral cities and healthy soil and food.’

For the EU, it seems changing consumption behaviour, preferably using kids to do so, takes precedence over real laboratories testing real innovations. To give itself a semblance of popular legitimacy, Brussels now wants to present its top-down scheme as a bottom-up, green, digital movement of youthful boffins in funky innovation start-ups.

The outlines of such a movement are already clear. It is shaping up as a Europe-wide environmental aristocracy that performs innovation in name only, and acts as an authoritarian bulwark against the genuine article.

James Woudhuysen is visiting professor of forecasting and innovation at London South Bank University. He is also editor of Big Potatoes: the London Manifesto for Innovation. Read his blog here.

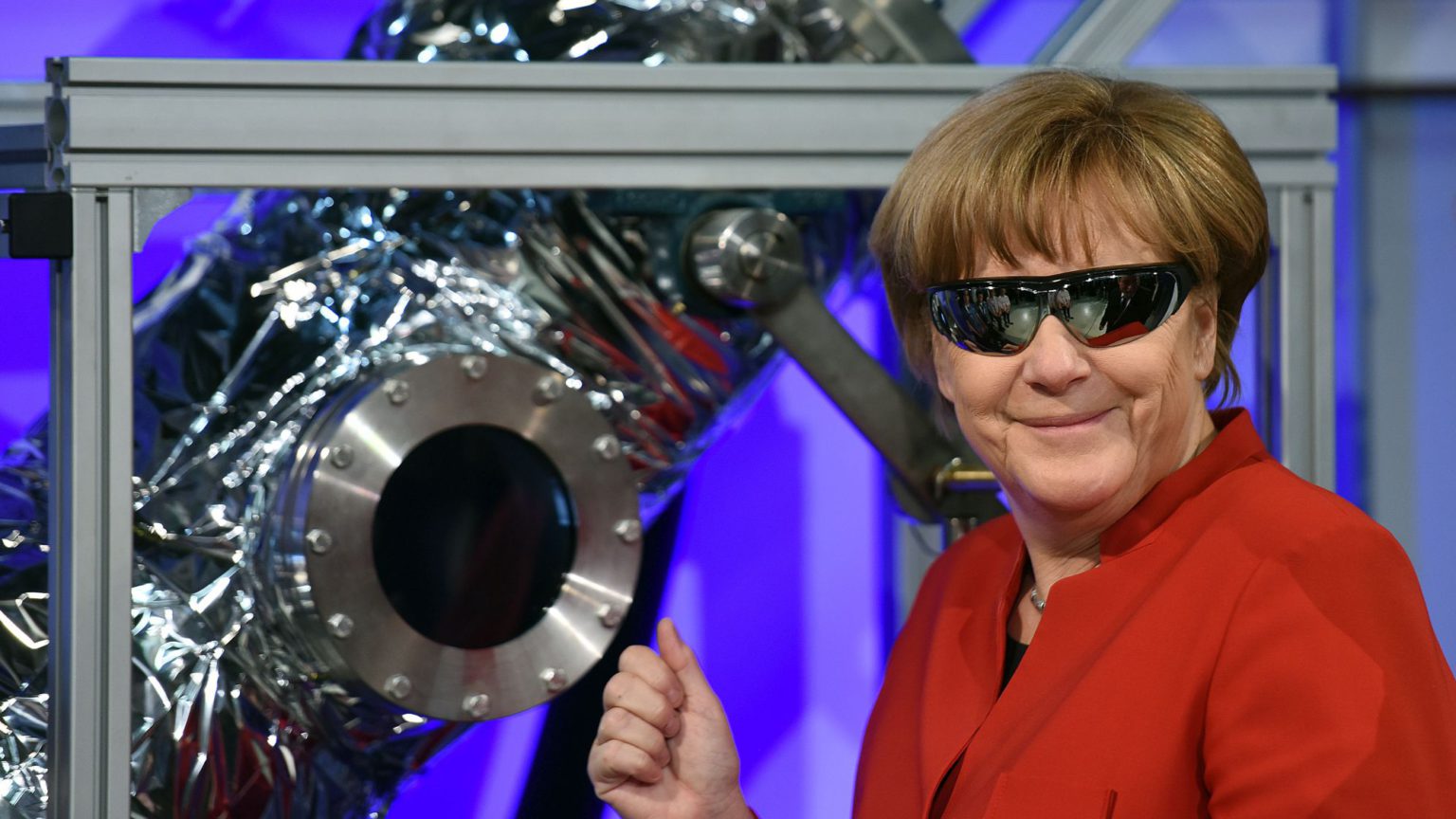

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.