Virtuoso: reckoning with nihilism

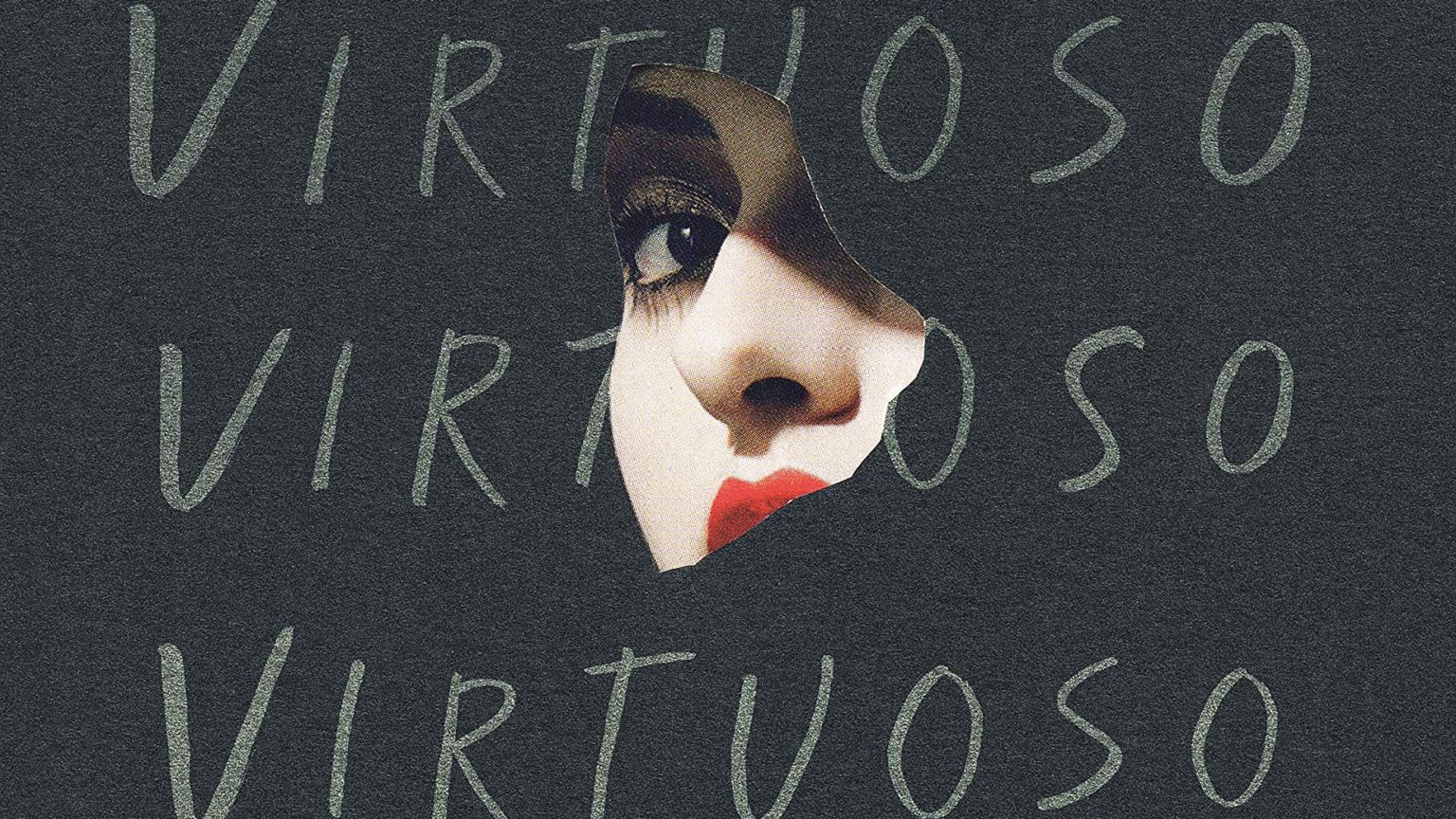

Yelena Moskovich's new novel is a morally complex exploration of doomed love.

Virtuoso, by Yelena Moskovich, a Paris-based Ukrainian-American writer, has been hailed as a ‘bold feminist novel’.

Focusing on often doomed, queer and lesbian love, Moskovich weaves together the lives of three sets of female protagonists: Jana and Zorka, two friends whose story begins in their childhood in 1980s Prague; Aimée and Dominique, two Parisian lovers; and Amy and ‘Dominxxika’, two wildly different women who meet each other in an online chatroom (most of their tale is told through snippets of their online conversations).

It may or not be a ‘bold feminist novel’, but it is definitely a strange novel. The characters are eccentric, to say the least. Zorka, for example, is a fierce non-conformist who as a child burned her mother’s fur coat and delighted in her ‘pee trick’ of urinating in front of her mother in the middle of their apartment. Another character is followed by a strange blue haze. And disgusting creatures appear from nowhere to commit horrible crimes.

At times, it works. It lays bare, for instance, the intensity of childhood rebellion and companionship. After Jana and Zorka shave off their first pubic hair they lie together, imagining they are floating above a world in flames: ‘And the more we burn the higher we get! Look now: There’s our ugly city and our ugly country, and our ugly world!… Even the stuff we thought was okay and even nice or really beautiful, it wasn’t, it’s not.’

The second sentence could almost be read as the central thesis of Virtuoso. While the characters may in part shed their teenage nihilism, the novel never ceases to delight in ripping the facade off things, trying to show that what appears beautiful or meaningful really isn’t. So, when Aimée attends a wake, Moskovich paints a spell-binding portrait of the emptiness of having to fulfil a purely social role, living according to the demands and expectations of others:

‘This dress, it fits her body and the occasion. It engulfed her and it erased her, it made her a silhouette of just the right woman. A black hole, a lapse in memory; someone else’s orgasm, someone else’s blood-rush, someone else’s pumping for life… waiting for someone else’s gaze to fill her ellipsis.’

If Moskovich’s writing sometimes soars, as it does here, she is never far away from the gutter, always ready to draw us back to the sheer bodyliness, and nastiness, of existence.

In this, there is something resolutely contemporary about Virtuoso. Lesbianism, androgyny, suicide, loneliness, bodily movements, selfishness and love that always ends in disappointment or worse – these are Virtuoso’s key elements. When conservative writers complain that modern art has turned its back on beauty, they have a novel like Virtuoso in mind. In one on-the-nose moment, love is even compared to shitting. (‘The lady therapist told me that our anus is actually an important muscle, just like our heart, and that all parts of our body, mind and spirit can help us exercise love.’)

There is a point to this persistent demystification of things. Moskovich rightly wants to say there is nothing ‘artistic’ about some of Virtuoso’s themes, be they rape or suicide, and that therefore any literary treatment of them has also to capture their brute nastiness.

But, through Zorka, Moskovich demonstrates the limits of such nihilism, this refusal to believe in the meaning or value of anything very much, and this attraction to the nasty. Zorka always calls the vagina a ‘cunt’; and ‘she had never in her life, ever seen a man and a woman say “I love you” to each other, where it wasn’t a threat’.

Then there is the rape of Jana. This is not a plot line merely designed to shock. It is the fulfilment of Virtuoso’s contention that sexual desire concludes with horrible actions. Indeed, sexual desire seems almost to draw characters towards something dark and nasty.

Moskovich reckons with the appeal of nihilism and nastiness. In doing so, she captures the temptation of not believing in anything beyond the body, without completely giving into it. And this is a considerable achievement.

Jacob Reynolds is a writer based in London.

Virtuoso, by Yelena Moskovich, is published by Serpent’s Tail. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.