The Democratic town that took a chance on Trump

Tom Slater reports from Erie, Pennsylvania, a Rust Belt city refusing to be written off.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

This report accompanies the release of spiked’s new film, Deplorables: Trump, Brexit and the Demonised Masses. Watch it now here.

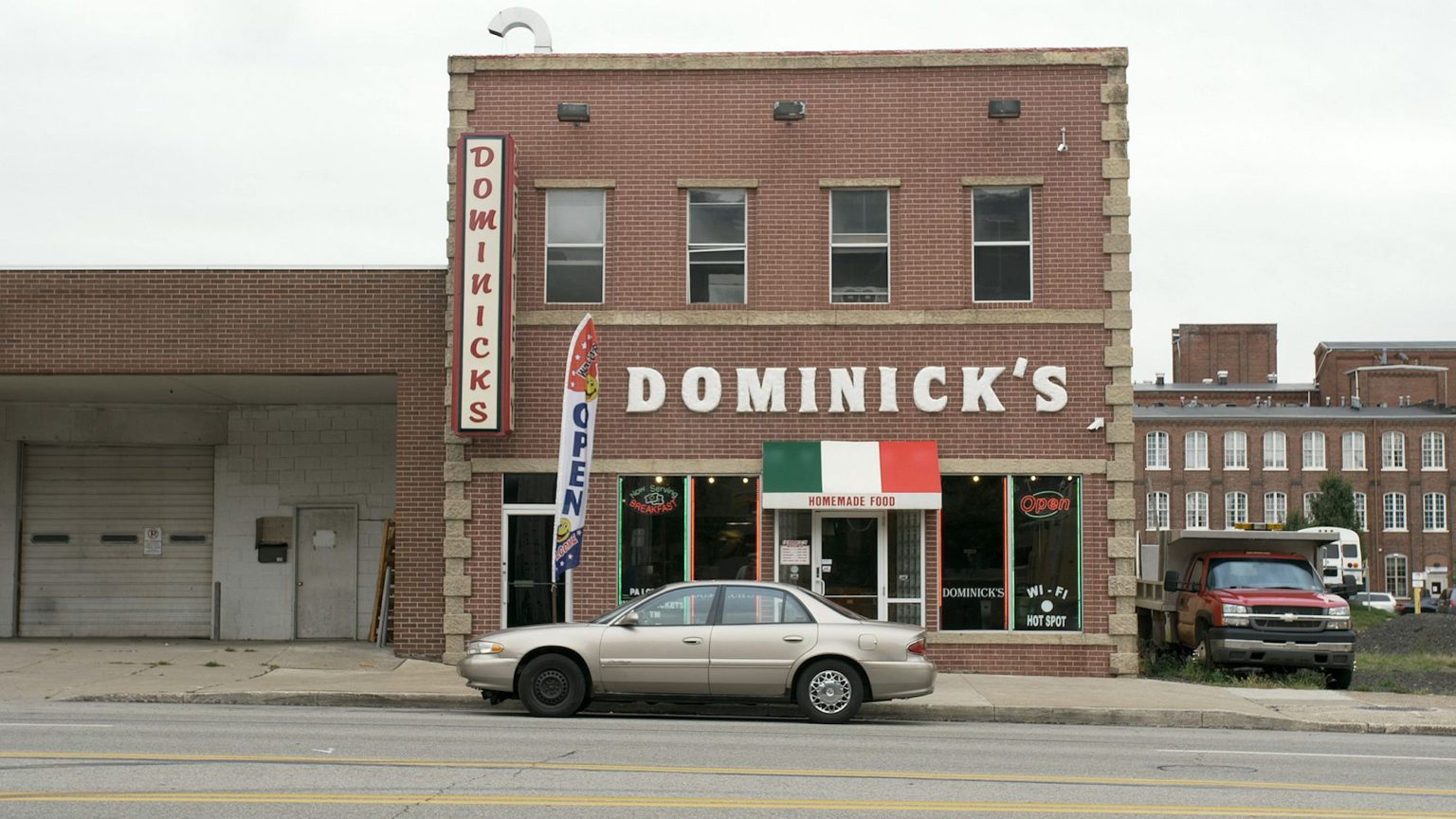

‘I was going to ask how was the food, but the clean plates speak for themselves.’ So says our server at Dominick’s Eatery, in the heart of Erie, Pennsylvania. We’d each just had a meatball omelette, this place’s speciality. The plates didn’t lie.

The spiked team were in Erie last September to interview people for our new film, released today, Deplorables: Trump, Brexit and the Demonised Masses. It’s about the populist revolts of 2016, and the anti-voter, anti-‘redneck’ fury it unleashed from the elites.

But Erie, which backed Trump, isn’t so easy to caricature. This Rust Belt county, on the edge of the Great Lake Erie, voted for Obama twice, before backing The Donald. Until 2016 it was a Democratic stronghold: a Republican presidential candidate hadn’t won here since 1984.

The owner of Dominick’s, Tony Ferraro, doesn’t want us to talk about politics – it’s one of the conditions of him letting us film in his establishment, talking to him and his staff and his punters, around lunchtime on an overcast early autumn day.

But there’s still plenty to talk about. Dominick’s – an Erie institution, founded more than 50 years ago by two guys called Dom and Nick, hence the K in the name – is a good place to start to understand the story of Erie, a rough diamond that has seen better days.

It’s on 12th Street, once the economic heart of this old manufacturing town. Now, it’s a graveyard to former glories – lined with empty factories with punch-card windows, some beginning to be reclaimed by nature.

Charles, the kitchen manager here, has been working at Dominick’s since 1989. Back then it was open 24/7, serving workers and their families in the day and graveyard shifters and bikers in the small hours.

‘We can’t stay open 24 hours now, just on weekends, because there’s just not enough business during the week’, he says. Though daytime custom still seems healthy: ‘They love the meatballs, the homemade sausage, they just can’t get enough of us.’

Tony arrives, and takes a seat at the counter for our interview. We soon get on to how much things have changed. ‘In its heyday, 12th Street, that was it, that was the main strip, a lot of factories, a lot of industry’, he says. ‘But when they’re gone, they’re gone, and ultimately that affects all the businesses around.’

Erie County was once a proud manufacturing town, and a thriving community. But in recent decades there has been an exodus of businesses, jobs and people. Since 2010 alone, it has shed more than 8,000 residents. As of 2018, the population stood at around 272,000.

It isn’t just blue-collar manufacturing jobs that have been lost, either. Government data, analysed last year by the Associated Press, suggest that since 2008 there has been an exodus of professional jobs, too, from accountants to computer workers to engineers – jobs that are increasingly, AP notes, ‘the backbone of the US economy’ as manufacturing dwindles.

Salena Zito, roving Rust Belt journalist and co-author of The Great Revolt: Inside the Populist Coalition Reshaping American Politics, says this is a big part of the story of how Erie – and America – went red in 2016. ‘Erie is a good microcosm of understanding how America went from supporting Barack Obama twice to supporting Donald Trump’, she tells me, at her home in Pittsburgh.

‘It is a county, a city, that is in transition and has been left behind for decades, I would argue for generations’, she says. ‘Job losses and population have really just bled throughout that area. Those kinds of things break up families. And when families break up, communities break up.’

From the Hammermill Paper Company to the plumbing-equipment firm Zurn Industries, big industrial and manufacturing companies were once central to the community. But none more so than GE Transportation, a division of the General Electric Company, which built locomotives in Erie for a century. At its peak it employed 20,000 people; everyone knew someone who worked at ‘The GE’.

No longer. GE Transportation was spun off and merged with the Wabtec Corporation this year. The Erie Times-News proclaimed it the ‘End of an Era’. It also led to a confrontation with workers, who called their first plant-wide strike since 1969, following Wabtec’s attempts to implement a diminished pay structure for new hires as well as mandatory overtime.

But Scott Slawson, president of the Local 506 of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (or UE), says things were going downhill long before the merger: ‘Over probably the past 30 to 35 years, many products we built here in Erie were shipped to offshore locations, and some within the United States… mainly to right-to-work states [which limit union rights] or other sites that are not unionised.’

The ‘final blow’, he tells me, came in 2013, when GE cut 950 jobs in Erie and moved one sixth of workers to a new facility in Fort Worth, Texas. And dwindling work at the plant didn’t just hit workers at GE. ‘Every single job here directly affects four jobs in the economy’, Slawson says, from suppliers to bars and restaurants.

He puts Erie’s decline down to a ‘perfect storm’ of political and corporate developments. ‘Our own government and businesses went on the attack against organised labour… and NAFTA [the North American Free Trade Agreement] played a role in sending a lot of the work that we do here in Erie to places like China, Mexico, Vietnam.’

So is this why Trump, who promised to ‘bring back our jobs’, connected with voters in Erie? Slawson, a Bernie Sanders supporter, says that he knew of members of his own union who backed Trump. But he thinks voters were as much repelled by the Democratic establishment as they were won over by the Republican insurgent: ‘Erie has been a Democratic region for a very long time and we’ve gotten a lot of lip service for a very long time… There’s always a promise of “we’re going to do better for you”. But nobody ever sees it.’

He cites Hillary Clinton’s failure to campaign in Erie as fatal (Trump packed out the Erie Insurance Arena with a rally in August 2016). ‘Trump made an appearance here and he made a lot of promises here in Erie. Now, has he carried through with any of them? No, he hasn’t. But people, at that point, were looking for something different. And let’s face it, Trump was different.’

One of the people at that August rally was Joe Orengia, a body-builder, Vietnam veteran and small businessman in his early seventies. We meet at his business, Joe’s Gym. As we walk in, he’s sat behind the counter in a ‘Veterans for Trump’ t-shirt. (He was so enthused by the Trump campaign that he even put out his own ‘Pump for Trump’ line of workout t-shirts.)

His enthusiasm has not waned one bit. ‘I finally see some hope, because things are getting better’, he says, as we sit down to interview him on camera, among the barbells and benches.

Orengia was brought up in a blue-collar Democratic family, but grew more and more disillusioned with the party as he saw the Erie of his childhood fade away. ‘My dad raised seven kids as a janitor. We had food on the table, we had a car, everything was going good. You couldn’t do that nowadays.’

He once worked as a bridge-builder and iron worker, putting up buildings at GE and Hammermill. ‘They’ve actually torn down half the buildings that I put up’, he says. ‘It’s nice because you see the lake now, but I don’t know how anybody’s going to make money looking at the lake.’

The jewel of Erie is the beautiful Presque Isle State Park, a wooded peninsula, lined with beaches, curling into the lake, drawing thousands in the summer months. Tourism, alongside a growing insurance and healthcare sector, is one of the ways in which Erie is trying to reinvent itself. But Orengia is unconvinced: ‘They’re putting up hotels and stuff like this. They’re dying in the winter. This isn’t a recreation town. Bring the industry back.’

During the 2016 race, he says anyone in Erie could see what was coming, even if the pollsters couldn’t. ‘I was driving eight miles. I counted 22 Trump signs. I counted two for – I think his name was – Gary Johnson. And I saw two for Hillary — and one of them said “Hillary for Prison”. But the polls say Trump’s losing, and I’m like: no way, fake news.’

In the end, Trump won a narrow victory in Erie, albeit one that overcame Obama’s 16-percentage-point win here in 2012. It was close to a 50-50 split, as Slawson is quick to point out to me. And a lot of it, he says, could be put down to who Trump was up against. ‘I think they saw Hillary Clinton as another career politician who wasn’t going to do anything to drive change.’

But for Orengia, at least, Trump was also a vote for something: for someone who might drive the sort of change that Hillary Clinton would not. ‘He’s giving us some hope here that it can change. Obama did the same thing, hope and change’, he says. ‘But… it didn’t work. So it’s time for a new idea.’

The Obama-Trump comparison comes up a lot here. This might be a surprise to those who are keen to present the Trump vote primarily as a ‘whitelash’, in the memorable words of former Obama adviser Van Jones on election night – a racist backlash stirred by the first black president and Trump’s xenophobic campaign.

But it’s an explanation that doesn’t map so easily on to Erie. For one thing, Erie has a long and proud history of welcoming refugees. According to a recent Washington Times report, no other small American city received more refugees between 2012 and 2016 than Erie – from Bhutan, Nepal, Sudan, Syria and Iraq. And for the most part, the report suggests, the newcomers have been embraced and welcomed.

Nor does the racism smear wash with Orengia: ‘I’ve got four biracial grandchildren. I love ’em to pieces. I love their fathers, they are the greatest guys’, he says, smiling, before getting serious: ‘It has nothing to do with racism… I used to live in the ghetto on the east side. Half my friends were African-Americans… And they come up with this race thing all the time. Knock it off.’

Whatever one thinks of particular politicians, even one as ‘different’ as Trump, places like Erie offer a valuable lesson in not writing off their supporters. Voters aren’t caricatures; they bring to the ballot box their own politics, motivations and histories, often springing from the problems affecting their communities. Those paid to pontificate about them would do well to try actually talking to them.

In their more generous moments, metropolitan commentators put the success of Trump in the Rust Belt down to a sense of hopelessness. People were lashing out. Perhaps there’s some truth to that. But in Erie, at least, there is also a palpable sense of hope, an insistence that things can get better – though the people I spoke to see change coming from different directions.

Orengia, when we spoke last year, felt like Trump was delivering for jobs and the economy: ‘I haven’t had a vacation in five years. Before, it was because I didn’t have the money to do it. Now I don’t have the time to do it.’ In July 2018, unemployment in Erie had hit an 18-year low, according to the US Department of Labor, but I’m sure even Joe would concede that Erie remains a shell of what it once was.

Slawson is, as you might imagine, less impressed by Trump’s record. For one thing, Trump’s steel tariffs, he says, have hit the locomotive business. But with the Erie strike coming amid an upsurge of union agitation across the US – from the West Virginia teachers’ strikes last year to the autoworkers strikes today – he has other reasons to be cheerful. ‘We need to start taking on a fight and say we’ve had enough of this crap. That’s what we’re seeing, and I’m proud to see it.’

That steeliness isn’t hard to find, even back on 12th Street, where a painting on a red-brick wall reads ‘Robust Belt’, next to a picture of Rosie the Riveter. Even in Dominick’s, where we still can’t talk about politics, you glimpse that optimism. ‘Erie has taken a hit, like all cities. It’s coming up slowly, but surely’, says Charles. ‘That’s what I like, that’s why I think I’m not ever going to leave here. Like I said, born and raised here, and I want to see the city get good again, honestly.’

Tom Slater is deputy editor at spiked. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Slater_

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.