Long-read

Kashmir: a tale of two mothers

A one-time homeland to Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs is being tragically torn apart.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Iftikhar was my favourite taxi driver while I lived in London. An elderly Muslim from Lahore, he spoke in lilting, lyrical Punjabi typical of that part of the world. In June 1999, as India and Pakistan fought the Kargil war, he was driving me to Heathrow when the conversation turned to the conflict. I asked what he thought. ‘Doctor sahib‘, he said, ‘when my mother had me, she was suffering from tuberculosis. She was weak and her milk had dried up. Her nextdoor neighbour was a Sikh woman who had also given birth. My mother asked her to breastfeed me. When you ask me about the war, what can I say? I was born of one mother’s womb; another mother suckled me. How can I choose?’

I thought of Iftikhar as India and Pakistan are again on the brink. On 5 August 2019, Amit Shah, India’s home affairs minister, announced in the upper house of the Indian parliament (Rajya Sabha) that a presidential order had been issued revoking Article 370, depriving the state of Jammu and Kashmir of its special status that conferred on it a certain level of autonomy, and fundamentally changing the relationship between India and Kashmir.

The immediate and long-term consequences of this Indian move will be far-reaching, and may be very damaging. No one can foresee the outcome and many will rightly be trepidatious. But at this critical juncture, it is important to realise the complexity of the Indian-Pakistani conflict over Kashmir, and its varied victims. Much of the media portrayal of the conflict is one between a Hindu nationalist India and the Muslim population of Kashmir. This is only partly true.

I come from a clan of Kashmiri Sikhs from Poonch, a beautiful district in Kashmir with the line of control (LOC) that divides India and Pakistan running right through it. Kashmiri Sikhs are ethnically distinct from Punjabi Sikhs, and were originally Kashmiri Brahmins (or Pandits, as Kashmiri Brahmin Hindus are commonly known).

There are several versions of when and why my family converted to Sikhism. One tells the tale of two brothers, Madan and Gopal, from Rishikesh who travelled north and settled in Poonch in the late 18th century. This chimes with accounts of Max Macauliffe (1841-1913), who traced the arrival of Sikhs in Kashmir as accompanying Raja Sukhjawan, a Hindu who was made governor of Kashmir by Timur Shah in the mid-1750s. Some historians believe Sikhism came to Kashmir during Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s rule in the early 19th century, while others believe it was Banda Bahadur (1670-1716), the Sikh general who created the Khalsa (the pure ones) in Kashmir. Bahadur was born in Rajouri, a region adjacent to Poonch to which he retreated, following a lost battle, in order to raise a fresh army. Regardless of the historical veracity of competing accounts, Kashmiri Sikhs have been a culturally, linguistically and ethnically distinct group for at least 200 years.

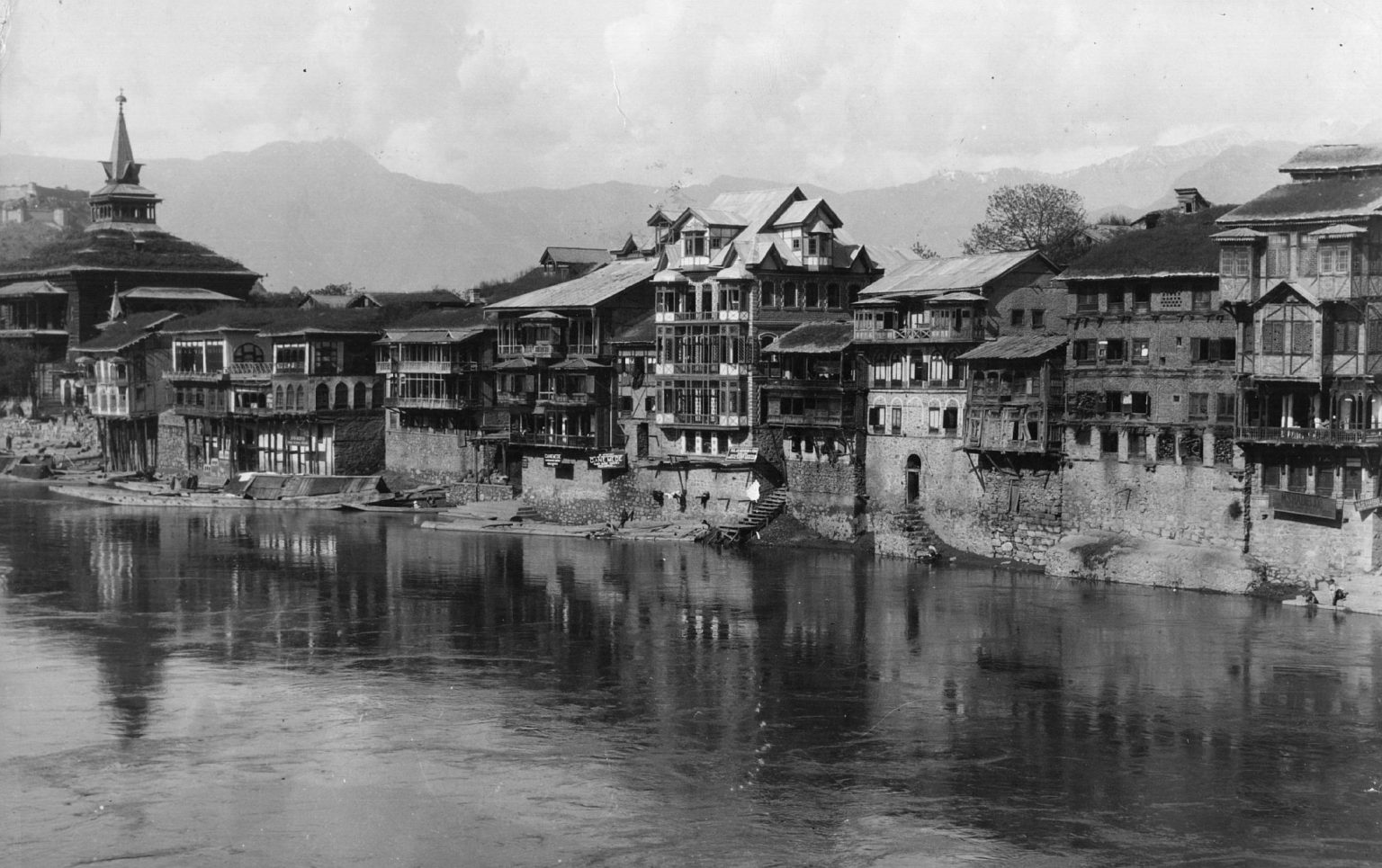

No more, though. Kashmir has been ethnically cleansed of its Sikh and Pandit populations, in a systematic and purposeful manner. Over half-a-million non-Muslim Kashmiris have been driven out of their homeland since 1990. Beginning in 1989 with the assassination of Pandit Tika Lal Taploo in Srinagar, a meticulously planned and ruthlessly executed campaign of terror was unleashed against non-Muslims. My paternal uncles owned two iconic bookstores in Srinagar ̫ Hind Book Store and Kashmir Book Store, famous with hippies, backpackers and the assortment of Western travellers who flocked to Kashmir and its idyllic beauty, and celebrated it, as Led Zeppelin did, in their majestic song ‘Kashmir’. But my uncles, fearful of the posters that appeared on walls claiming Islamist rule, the masked men with Kalashnikovs forcing locals to change the time on watches to Pakistan Standard Time, and threatening messages broadcast from mosques, left everything they knew and owned behind, to live as refugees in neighbouring Jammu. They were lucky to escape unharmed. Girija Tickoo, a young Pandit woman, was abducted in June 1990. Her mutilated body was found on 25 June 1990. She had been raped and then her sawed in half, possibly with a carpenter’s saw, while still alive. Sarla Bhat, a 24-year-old nurse, was tortured and gang-raped over five days in April 1990 before being shot and killed. The list of atrocities against Pandits is long and horrific. And the indifference of the world startling.

Perhaps it was ever thus. In 2010 my mother, terminally ill with cancer, agreed for me to video-record her narrating her life story, so my young children would know her, even if only through that movie. She was of the generation that spoke little, and whose waking hours were consumed by a thousand chores, big and small, and who had to look after a large family with very little money and none of the accoutrements of modernity. Over two hours she told me things that I neither knew nor could have imagined.

Several people in my extended family had been killed by Muslims in the 1947 partition madness. In revenge my great grand uncles had gone on reprisal killings. In the massacre of one family, they abducted 10-year-old Muslim girl. When my great grandfather found out, he was extremely angry and distressed. He insisted that the child be taken back to her family, but there was no family she could return to. He adopted the girl, and when she turned 13 he married her to his 13-year-old son. I knew her as an aunt with piercing blue eyes and a perpetual hint of mischief on her face. I spent a lot of my childhood playing in her house with her son. My dying mother told me that her real name was Fatima, that she never spoke about her past, and died taking all her secrets and untold griefs with her.

That very year my brother-in-law Gurdev was contacted by a family from Lahore claiming to be his cousins. Gurdev was born in Lahore. His parents fled at the start of the killings in 1947. His paternal aunt refused to leave the family home, insisting that the ‘madness would pass’. The family was attacked and everyone killed but for two young boys, who had to choose between being killed or converting to Islam. They converted, and 60 years later, thanks to the internet and social media, traced Gurdev. The families agreed to meet as the Pakistani side was planning a trip to India. A date was set and my sister, Gurdev’s wife, started planning a meal.

The choice of dishes was problematic. The Muslim part of the family wanted only halaal; my sister refused to cook anything but jhatka meat (the Sikh way of killing an animal, with a single stroke severing the head to minimise suffering). The only option was to cook a vegetarian buffet.

Gurdev’s cousins arrived, attired in the Pathan garb of Kamaeez Shalwar, and with Muslim skull caps. Gurdev greeted them in all his turbaned glory. The cousins read the Namaaz in my sister’s Sikh household before eating. There were tears of joy and sorrow, much reminiscing of what little each could remember from their turbulent past, a long list of all the uncles, aunts and peers who had passed away, and proud displays of the achievements of the younger generation. No one mentioned partition, politics was studiously avoided, and religious differences, simultaneously visible and completely ignored, were not allowed to get in the way of the palpable intimacy of the occasion. Like Iftikhar’s two mothers, here were those of the same flesh and blood, brought up by two different mother cultures. They would not eat the same meat, but could love each other nonetheless.

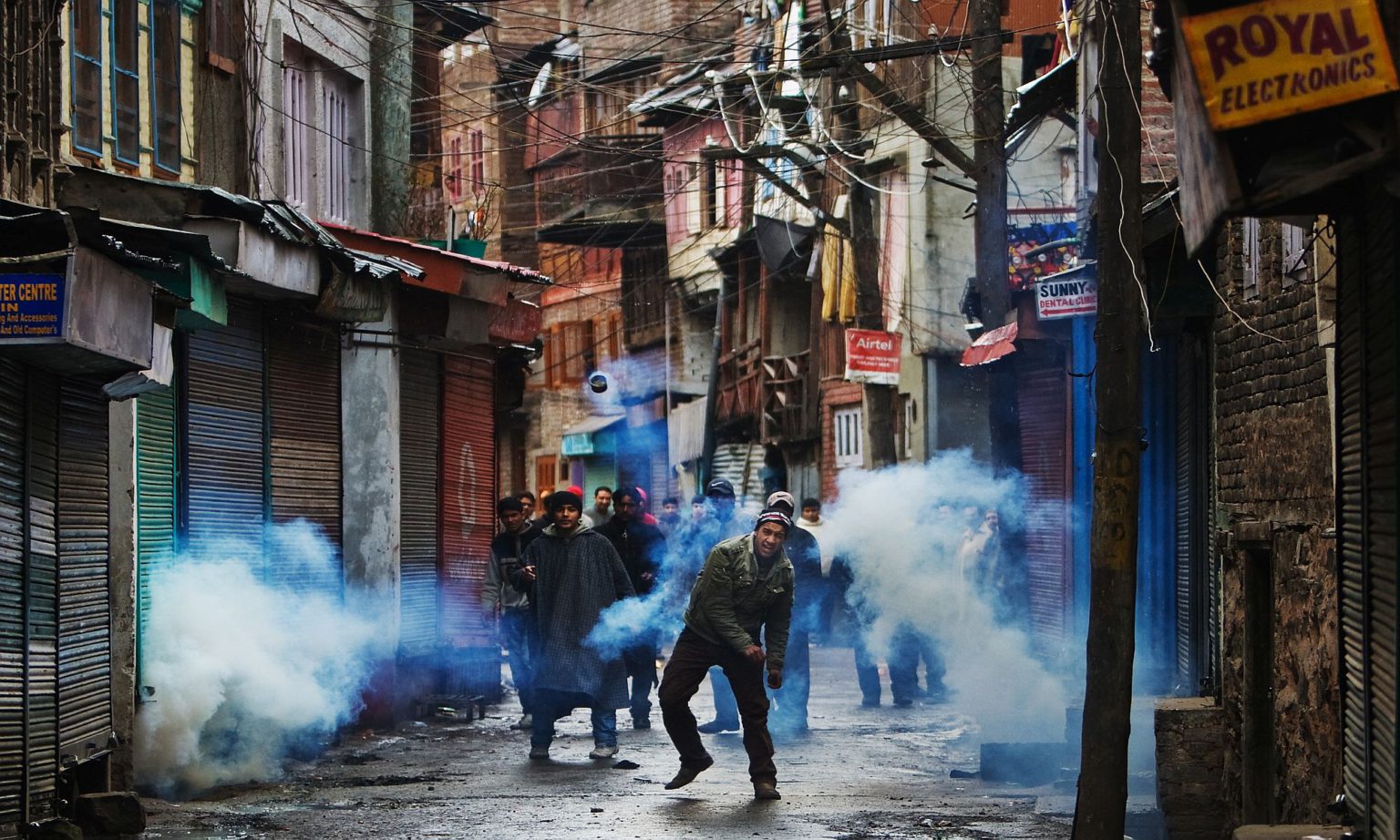

Kashmir has been bleeding profusely for 30 years now. Kashmiris, once famous for their pacifism, have turned against each other, and one community has driven the other two out of the land. Kashmiri Muslims have their own long list of accumulated tragedies and suffering. When I was growing up, Sikhs used to make fun of their avoidance of conflict by telling a story about 100 Kashmiri Muslims who flee from a confrontation with a Sikh armed with a stick, explaining, ‘What could we do? We are all alone, but the Sikh and the stick were two!’ That famous pusillanimity is long gone. Fuelled with rage at ill-treatment by Indian forces, armed by Pakistan, infiltrated by ISIS-trained killers, Kashmiri Muslim youth are driven in hordes into extremism. In the process, they have forgotten their ties with their Hindu and Sikh brothers and sisters, whom they perceive as the enemy.

There are no villains or heroes here. The geopolitics of Kashmir, the nationalistic frenzy being whipped up, the macho posturing and duplicitous diplomacy, the raw pain of individual and collective devastations, all point to a continuing catastrophe. Pakistan sees Kashmir as its revenge for its own dismemberment and the creation of Bangladesh. India sees Kashmir as absolutely vital to its national security. Neither side will relent, while Kashmir bleeds from a thousand cuts. Kashmir seems trapped between two punitive, vindictive fathers. There is no healing and no soothing mother around, just perpetual distress and hardship.

Meanwhile, the world media has an easy interpretation of the Kashmir problem – a nationalistic India persecuting a Muslim minority state. It is expedient to focus on the tragedy as one only of Kashmiri Muslims, since for many, Kashmiri Sikhs and Pandits do not meet the criteria of victimhood. Kashmiri Hindus can’t be considered victims because they are, well, Hindus. Since India is supposedly in the grip of Hindu nationalists, any suffering Hindu group can be ignored, akin to the idea that Jews can only be oppressors because of the plight of Palestinians. The victimhood of Palestinians automatically places Jews in the oppressor box. So it is with Kashmiri Hindus, although they are ethnically, politically and even on religious grounds far removed from the Hindus of central India.

Moreover, the Sikhs won’t claim victimhood. Deeply ingrained in the Sikh psyche is the requirement to stay in Chardi Kalaa – spirit in ascension. Sikh history is a litany of persecution and massacres by the Mughal rulers of India. The Sikh prayer has a section where the torture of Sikhs is graphically described and blessing sought for the souls of those martyred. The descriptions – of Sikhs scalped and bodies dismembered, sawed and broken on the rack – would not be allowed in a BBC news report without the warning: ‘Some listeners might find the contents distressing.’ Every Sikh child hears these descriptions at every prayer, which ends with ‘May the Sikhs be in Chardi kalaa, may all be blessed by the will of God’. To be a Sikh is to stay upright, righteous and resilient. Sikhs have lost many battles, but have never been defeated; for to be a Sikh is never to accept defeat. Such a culture does not seek or fetishise victimhood. Sikhs seek no comfort, and none is provided.

But that does not make their suffering any less painful or less deserving of world attention. The elders of my clan are dying, holding on to whatever remnant of Chardi Kalaa they can muster. Soon they will all be gone. The world will move on. My clan painfully watches its own destruction, aware that no one cares. They are victims of a denial of their victimhood.

Kashmir’s tragedy encapsulates all the ethnic, religious, territorial and cultural conflicts that currently ravage the world. From the legacy of colonialism to the geopolitics of the post-9/11 world, Kashmir puts in stark contrast the world’s modern fissures. To see it entirely as a problem between Hindu nationalism and Muslim victimhood is to miss the messy complexity and ignore the plight of all of Kashmir’s victims.

Swaran Singh is professor of social and community psychiatry at the University of Warwick and an NHS consultant psychiatrist.

Pictures by: Getty Images.

No paywall. No subscriptions

spiked is free for all

Donate today to keep us fighting

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.