Long-read

An appeal from Old Labour to New Labour

Why Labour should become the party of Brexit.

‘Political problems do not primarily concern truth or falsehood. They relate to good or evil. What in the result is likely to produce evil is politically false; that which is productive of good, politically true…’ (Edmund Burke, An Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs, 1791)

Labour is split from top to toe. Party MPs are reluctant to say much because the split stretches far beyond Brexit into the prospect of de-selection. Many in the New Labour Blairite wing can’t get along with their leader or their voters. Many in the New Labour Momentum wing can’t get along with their voters or their MPs. Caught either way, but at the same time desperate to put clear blue water between itself and the Tories, Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour is in a dilemma. It has tried standing for all possible opportunities, but strategic opportunism only works in predictable situations. In unpredictable situations, where the vote is volatile, and wilful, all possible options just looks like a mess. In fact, it looks like the EU’s way of doing business: one step at a time, the blandest of statements, see what gives. Sometimes history and gut instinct work better.

The Appeal

Get real. For the first time in a hundred years, Labour faces a working-class electorate that it doesn’t understand and doesn’t know. Too many Labour MPs talk about the working class as if they were in need of social workers, not representatives. They should get real: it is the Labour party that has left the working class rather than the working class that has left the party; and if the party becomes more aligned to Remain, it will completely lose its bearings.

Get hard. Shadow Brexit secretary Keir Starmer and others have to acknowledge that there is no ‘Labour Brexit’ any more than there is a ‘Tory Brexit’. There is only an EU Brexit intent on teaching its member states a lesson in not leaving. Whatever outgoing Tory leader Theresa May’s failings, the Withdrawal Agreement was Brussels’ deal as well as hers, and Labour shadow ministers might bear this in mind when they presume how much easier their re-negotiations – presuming they get some – are going to be. Liberal empires like the EU do not coerce their members with armies and police — they rule by courts, commissions, delegated powers and the prospect of endless negotiation. The only easy negotiation will be a Remain negotiation. Brexit means hard ball.

Get clear. For the UK, Brexit has become an existential crisis, not a trade treaty. For the EU, it always was an existential crisis and those Brexiteers who thought it was going to be easy were guilty of Business Marxism where only money matters. In fact, May’s deal was not a trade deal or even the prologue to a trade deal. It was 585 pages of political equivocation and adjournment at the UK’s expense. At £39 billion, it didn’t come cheap either. Only Tory self-preservation gave it a cat in hell’s chance and even that proved insufficient.

Labour should come out in favour of a clean-break Brexit that says enough is enough: first, because it is true, enough is enough (and Labour would not be alone in thinking that); and, second, because we are going to leave without a deal in any case, and it is better for Labour to come out on the back of history and instinct rather than by default, or trailing in Boris Johnson’s wake. Deal-making only promises to prolong the national agony. Let’s get clear, let’s restore our self respect, and let’s get on with trade talks as trade talks and not some other thing.

Too many Labour MPs talk about the working class as if they were in need of social workers not representatives

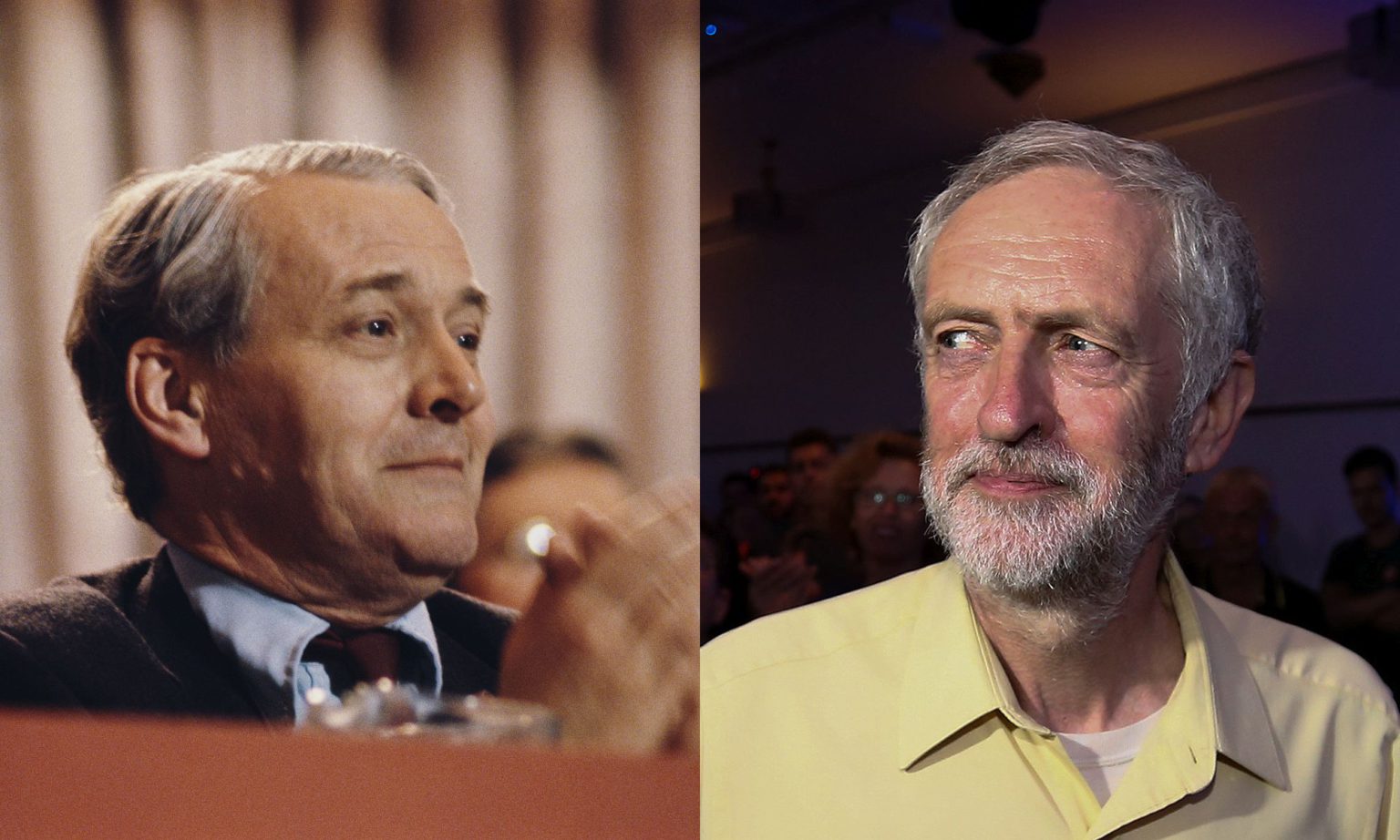

Get left. Labour’s old left position was always Eurosceptical. The EU has its origins in the 1952 European Coal and Steel Community. There is no way Clement Attlee’s Methodistic Labour movement would have agreed to joining an organisation conceived by Catholic conservatives devoted to rationalising British coal and steel. Hugh Gaitskell talked about joining Europe but losing a thousand years of history. Peter Shore, Bryan Gould, Michael Foot (and George Orwell) talked about socialism as essential to the national genius. Tony Benn warned about the Commission’s anti-democratic instincts mixing with the British Establishment’s taste for secrecy. He called the original act of joining a coup d’etat against parliamentary democracy.

In essence, this has been Corbyn and McDonnell’s point of view over the years, but New Labour, their New Labour, finds more in sophistry abroad than achievement at home, and the Labour leaders find themselves stuck between their judgement and their ambition. It’s a Shakespearean Tragedy. The man admired for his principles is separated from his principles by those who admire him for his principles.

Get together. We find ourselves in the unprecedented situation of having a parliament not only unable to express itself, but unable to express that which it asked us to express on its behalf. The country is not stupid and knows this, but without representation, it needs a lead, a style, a lyric, to make itself known. Call it patriotism, if you like. There are only so many speeches the Labour leader can make about human rights in the world and expect to be heard here. Labour must speak for the country as a whole, because without political democracy there can be no social democracy, and without the revenue-raising powers of the state there can be no road to fairness. All other self-dividing socialisms (built ad infinitum on race or gender or class or region or religion) are bullshit socialisms.

Get ready. Tory Leavers saw no deal as the only way out of the Brussels mess. But this ceased to be wise for them the moment a stalled trade deal in Belgium turned into a constitutional crisis at home. That the crisis could have happened under any minority government is true, but that it happened under a deeply unpopular and divided Tory government is Labour’s best chance. The Tories now face meltdown, not only in any future cabinet, but in party and electorate as well. Their new leader is going to find himself sitting in a pool of water unable to call an election without securing an exit and unable to secure an exit without calling an election. Sooner or later a General Election is the only constitutional solution, and Labour must be ready with a clear but realistic line that deals with Nigel Farage as a one-trick pony and the Tories, however they reconstitute themselves, as a dead horse flogged.

At the same time, Labour must signal its intentions to its traditional voters, and to itself, by calling for policies that were common sense only yesterday: that democracy is a good thing; that the integrity of the nation state and its borders combined with a strong immigration policy is one of the most important ways of lowering popular anxiety; that the principle and practice of public service is good as well as useful; that central and local government need each other, and could be and should be flanked by more money and power for the north; that state interventions can save good businesses as well as improve bad ones; that without trust and common purpose – the non- contractual obligations on which all contracts depend – there is no society. That all this will lose votes as well as gain them I have no doubt. But trying to scoop from both sides while hiding in the middle only causes drift. If Labour doesn’t want to be a working-class party, it should say so.

Tony Benn called the original act of joining the EU a coup d’etat against parliamentary democracy

Get with the many. So many MPs talk about what they learn ‘on the doorstep’, you wonder why they never get into the kitchen where people really talk. Look at the Commons’ benches and wonder how so few can claim to represent so many. The trust between the British people and the House of Commons is so slender, so long lived and so – all things considered – effectual, it must be some sort of political miracle. But too many years ignoring majority wishes on core issues (too many to count) has eroded the trust of people in parliament to such an extent that the consequences of a second referendum would be terrible. Nobody would have a clue as to what the vote actually indicated according to the questions put and not put. But whatever it indicated, a second referendum would, in the end, be seen as a shameless attempt by the few to thwart the will of the many.

Burke reminded us that the idea of a people is the idea of corporation made, ‘like all legal fictions’, by ‘common agreement’. Once the legal fiction is exposed as such by the violation of this common agreement, in this case, the few thwarting the democratic will of the many, then the relationship between parliament and the people really will be in trouble – in other words, once Humpty Dumpty falls, he might not be put back together again. I am being as light hearted as I can on this very serious matter, but a second referendum would be as flagrant a rebuttal of democracy as any in our history.

Be happy. That said, in spite of all the talk of humiliation and disgrace we are accused of heaping upon ourselves, it is worth noting that through it all, apart from the occasional assassinator’s milkshake, there have been no civil disturbances, the markets have remained steady, and the economy continues to grow. No other EU country has offered its people what parliament (for whatever reason) offered us and that, with all due humility, might be reason for a bit of pride. MPs might have endangered constitutional government with their March usurpation of its parliamentary agenda, but far from feeling humiliated or ashamed at scenes in the Commons, there are times when I have felt elated – elated at the smash and grab, the eye-to-eye exchanges and the blistering performances from people I never normally think about – Michael Gove for instance, or the attorney general. Can you imagine Jean-Claude Juncker coping at the dispatch box? EU debates look prefabricated and frictionless in comparison. The European Parliament in Strasbourg, for instance, is designed so that all look to the front while sitting behind banks of screens.

Whatever side they’re on, it is hard to imagine tyranny when MPs are personally known to each other, are personally accountable to their constituencies, and at liberty to speak face to face in a language they understand. There are times when democracies have to war with themselves just to show they are alive. Whatever the log jam, at least we are alive and kicking. It is silent regimes we should fear, not barnstorming ones, and it is high time Labour actually spoke in favour of our democracy as if it believed in it.

A second referendum would, in the end, be seen as a shameless attempt by the few to thwart the will of the many

New Deal Brexit. This has not been a good time to be prime minister, we know that. But, as we young Marxists used to say, ‘objectively’ speaking Mrs May inherited a political conjuncture of deep contradictions – inside her cabinet, her party, and parliament. The best time to kick a prime minister is when she’s down, and, boy, May has had to deal with her fair share of inverted snobbery and sly misogyny along the way. For all that, she was the only game in town until Boris came along and the fault is Labour’s. It is time to take a political risk, turn to what Antonio Gramsci called the ‘national popular’ and give it another go. What kind of go?

Let’s go for a ‘New Deal’ Brexit based on a clean break from the crisis tied to a Rooseveltian programme that signals security and sovereignty.

An if only appeal

There is, of course, no chance of New Labour taking heed of any of this. Any of it. It is a middle-class party now, and the shock of going for Leave without waiting for it to hit them would frighten just about everyone from the Blairites to the Momenta. It’s hard to see Jeremy explaining his sudden clarity of political purpose to Andrew Marr and the Remain commentariat.

But you never know. Mine is an ‘If only’ appeal. If the the Guardian’s ‘If only Labour would come out unambiguously for Remain’ is feasible, then so is my ‘If only Labour would come out unambiguously for Leave’. Mine is more feasible, actually, given Labour’s history, and given that Burke was right in supposing that politics is about lesser evils rather than greater truths. In his 1791 Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs, Burke lost his reputation in the party by appealing against its support for the French Revolution. No matter, in the end the revolution was followed by terror and autocracy, and Burke was proved right. Contrary to first impressions, perhaps, politics is a long game.

Robert Colls is a professor of cultural history at De Montfort University, and the author of George Orwell: English Rebel, published by Oxford University Press. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).) An earlier version of this piece was published in the New Statesman.

Picture by: Getty Images.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.