The truth about Chernobyl

The shocking truth about the Chernobyl disaster is how few people it killed.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

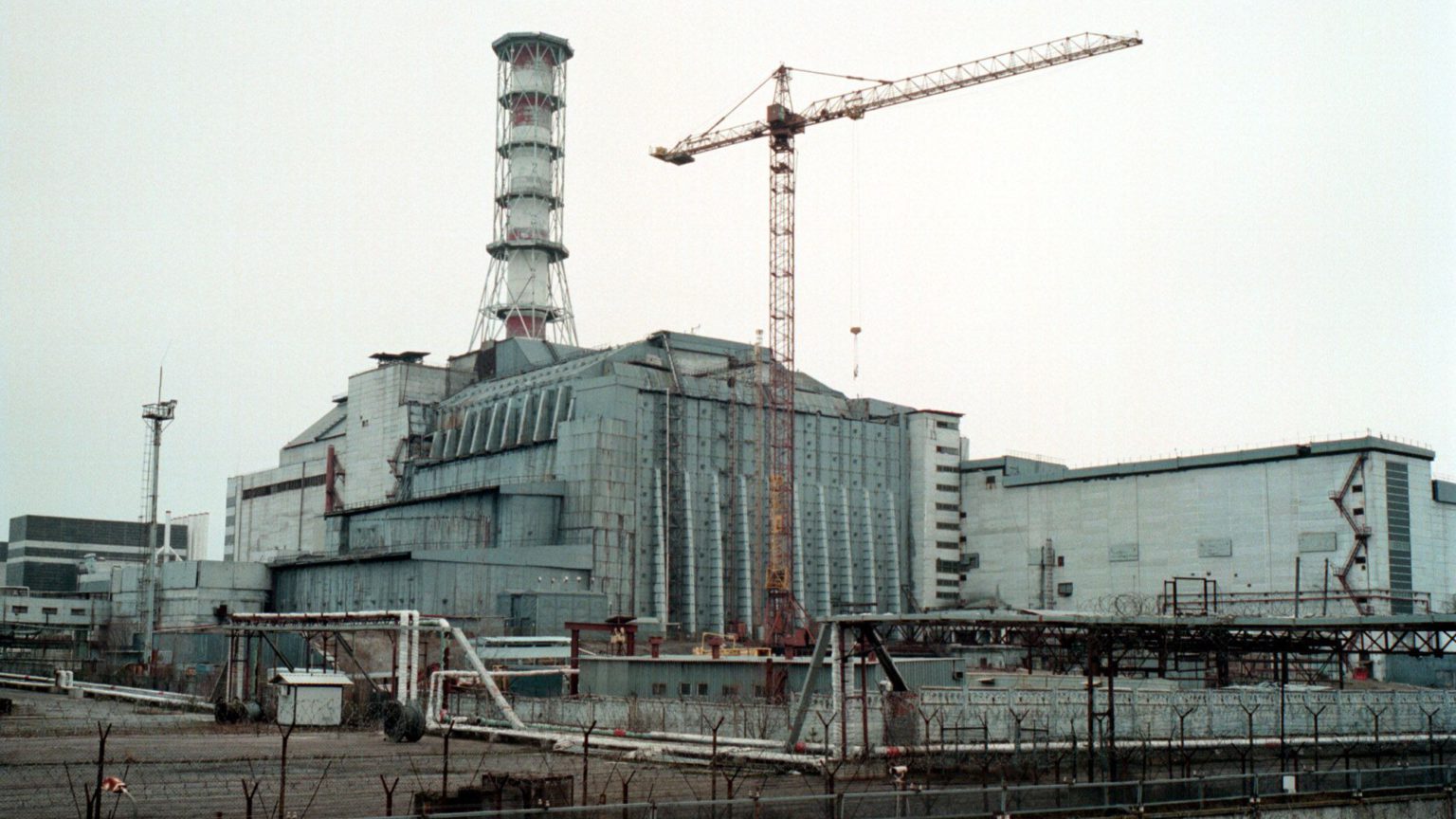

In 1995, nine years after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in Ukraine, I spent six months working at the heart of it all. At that time, I was the only Westerner permanently based at the site. The scale of the fallout, which displaced hundreds of thousands of people and affected millions living in designated contamination zones, was massive.

In 1986, following the disaster, the rescue effort was courageous and inspirational. But there was also an inexcusable, criminal cover-up by the Soviet authorities, led by the then leader of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev. The West was also slow to expose the magnitude of the disaster. Undoubtedly, there was an initial hesitation to criticise Gorbachev, as Western leaders were courting him at the time. Following the nuclear disaster of Three Mile Island, Pennsylvania in 1979, Chernobyl was also a hammer blow to the global atomic industry – not least because industry figures had repeatedly and misleadingly claimed that a full nuclear core meltdown could never happen. This downplaying of the disaster led many to distrust the official accounts.

Kate Brown, a professor at MIT, specialising in environmental and nuclear history as well as the Soviet Union, is the latest to cast doubt on the official version of events. Her new book, Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Future, sets out to expose a 33-year cover-up, in which the United Nations was in cahoots with the KGB and Western intelligence agents. This cover-up, she argues, was designed to downplay the horrendous health consequences of the disaster, both to protect the reputation of the Soviet Union and to prevent lawsuits arising in the West against the nuclear industry.

The UN estimates of fatalities were first published in 2005 in the landmark Chernobyl Forum Report. Its research and publication was led by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) on behalf of – and endorsed by – eight UN agencies and the governments of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine. The report assessed all the epidemiological evidence in a collaborative effort involving hundreds of experts. It found that there had been fewer than 50 deaths directly attributable to radiation from the disaster – there have been a further four deaths directly caused by Chernobyl since the report came out. Almost all of those who died were highly exposed rescue workers, many of whom died within months of the accident. The UN also predicted that there could be up to 9,000 Chernobyl-related deaths from cancer.

In response to the UN’s 2005 report, Greenpeace claimed that the death toll could be as high as 200,000.

Manual for Survival sets out to explain this ‘Grand Canyon-sized gap between the UN and Greenpeace estimates of fatalities’. Brown argues that decades after Chernobyl exploded there is still a need for a large-scale, long-term epidemiological study of the consequences of low-level radiation on human health in the affected areas. That may be so. But this does not itself prove a cover-up.

Brown also wants us to believe that after Fukushima blew its top in 2011, scientists told the public that they had no certain knowledge of the damage that could be caused by exposure to low doses of radiation as a result of the accident. Yet she provides no evidence of them claiming ignorance on this subject that is well understood by experts. She also argues that because of our failure to learn the lessons of Chernobyl, we are stuck in an ‘eternal video loop’, with the same scene of nuclear disaster playing over and over again, from Three Mile Island and Chernobyl to Fukushima. She accuses Japan’s scientists in the wake of Fukushima of ‘reproducing the playbook of Soviet officials 25 years before them’ by also downplaying the consequences of the disaster.

But Brown seems to inhabit a parallel universe. If anything, there is unnecessary panic about the supposed impact of low-level radiation. Far from downplaying the consequences of Fukushima, the official response has been overly precautious. An exclusion zone was created around the site, which largely exists today, though the nearby town of Okuma has since been declared safe for residents to return. Professor Geraldine Thomas of Imperial College, London, one of Britain’s leading researchers on the effects of radiation on the human body, told the BBC in 2016 that the radiation levels in the exclusion zone pose little risk to human health: ‘There are plenty of places in the world where you would live with background radiation of at least this level’.

A key case study in Brown’s Chernobyl cover-up theory is the story of Keith Baverstock. Baverstock was one of many courageous scientists and doctors who battled to convince the World Health Organisation (WHO), his employer, that the Chernobyl disaster had resulted in an unexpected outbreak of thyroid cancers among children. They discovered and publicised the fact that radioactive iodine (iodine-131 and caesium-137) was more carcinogenic than was previously thought. But Brown understates the fact that Baverstock and his colleagues won their battle. The final Chernobyl Forum report of 2005 incorporated their findings. What’s more, Baverstock repeatedly told the media that the biggest cause of health problems among people living in territories affected by low-level radiation was increased anxiety and stress levels, fanned by scaremongering.

Baverstock continued to criticise the Chernobyl Forum after he left WHO. He offers the most considered interrogation of the Chernobyl Forum findings that I have read. Along with his colleague, Dillwyn Williams, Baverstock criticised the conflicted politics behind the Forum and the impact this has on its research. He has pointed out the limits of the existing body of knowledge and called for more intensive research into the long-term effects of Chernobyl. He correctly said that we won’t know for sure the full outcome on human health for decades – the real death toll might still emerge because low-level radiation impacts are difficult to detect. But while Baverstock has advanced important criticisms of the UN’s figures, he has never endorsed Greenpeace’s speculative inflation of the evidence.

In contrast, Brown misrepresents much of what was uncovered by scientists in the wake of Chernobyl. She does so, presumably, in order to back up her claim that the Chernobyl exclusion zones will have to remain abandoned for much longer than anybody expected. (They are being repopulated gradually already.) Her claim is based on a misunderstanding of the science. Brown says it will take between ‘180 and 320 years’ for caesium-137 to disappear from Chernobyl’s forests. But the half-life of cesium-137 is 30 years. Her misunderstanding is based on an article in Wired, which has since been updated to reflect the science of half-lives more accurately. In other words, Brown is basing her conclusions on secondary sources written by people who failed initially to understand what they had been briefed by scientists. Meanwhile, in the real world, according to Professor Jim Smith of the University of Portsmouth, while the Chernobyl exclusion zone is still contaminated, ‘if we put it on a map of radiation dose worldwide, only the small “hotspots”’ would stand out’.

In the final chapter of Manual for Survival, we finally learn what Brown considers to be a more credible estimate of the total number of existing and expected fatalities from the Chernobyl accident. And once again we see there isn’t any real evidence or credible sources to support her thesis: ‘Off the record, a scientist at the Kyiv All-Union Center for Radiation Medicine put the number of fatalities at 150,000 in Ukraine alone. An official at the Chernobyl plant gave the same number. That range of 35,000 to 150,000 Chernobyl fatalities – not 54 – is the minimum.’ In reality, if even half or one-third of those deaths actually occurred, this would be impossible to hide.

In the end, the shocking truth about Chernobyl is how few people were killed or made ill by the radiation.

Paul Seaman is a communications professional based in Zurich, with specialist interests in energy and crisis management. Visit his website here.

Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Future, by Kate Brown, is published by Penguin. (Buy the book from Amazon (UK).)

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.