Long-read

In defence of the minority of one

The building block of democracy is individual liberty.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Democracy means that the people rule, and, according to Aristotle (who was himself no fan of democracy), ‘liberty is the first principle of democracy’. Aristotle reasoned in The Politics that the ‘results of liberty are that the numerical majority is supreme, and that each man lives as he likes’. Democracy doesn’t necessarily promote liberty; democracies can (and often do) suppress people’s freedom, sometimes for good and sometimes for bad. But liberty leads inexorably towards democracy, because there is no other way to reconcile the competing desires of free and equal individuals.

So: liberty first, democracy second. Countries conceived in liberty, like England and its offshoots in the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, tend to support strong and stable democracies. Even in South Africa, where the ancient liberties of Englishmen were until very recently restricted to a small minority of the population, a solid democracy has been built on a foundation of individual liberty. Lacking that foundation, it took France five tries to build a lasting democracy – assuming that the Fifth Republic outlasts the gilets jaunes protests. Democracy without liberty is a house built on sand.

Alexis de Tocqueville (who was also no fan of democracy) wrote in Democracy in America (1835) that liberty was ‘a necessary guarantee against the tyranny of the majority’ in a democracy. Not that he particularly approved of liberty. He thought that the use of liberty of association to oppose the tyranny of the majority was ‘a dangerous expedient … used to obviate a still more formidable danger’. Tocqueville anticipated that all sorts of evils would arise from the tyranny of the majority in America, though he averred that they were not yet common ‘at the present day.’

Nonetheless, Tocqueville thought that ‘if ever the free institutions of America are destroyed, that event may be attributed to the unlimited authority of the majority’. And there, the fashionable political scientist of today will let the quotation end. But in Tocqueville’s original, the sentence continues: ‘which may, at some future time, urge the minorities to desperation, and oblige them to have recourse to physical force’. So Tocqueville’s majoritarian democracy doesn’t end in the tyranny of the majority after all. It ends in the armed overthrow of the government… by the minority.

In Tocqueville’s day, that was indeed how democracy ended – in France. The French Revolutionary democracy, if you can call it a democracy (Tocqueville did), quickly degenerated into anarchy and dictatorship. Throughout Democracy in America, Tocqueville seemed mystified that the same thing had not yet happened in America. He was convinced that directly elected legislatures like the House of Representatives were bound to impose a tyranny of the majority, and he advocated a strong executive with ‘a certain degree of uncontrolled authority’ to balance the mob rule of Congress.

Democracy without liberty is a house built on sand

How things have changed. Political scientists still love Tocqueville, but with Donald Trump in the White House, it’s that ‘uncontrolled authority’ of the executive that they worry about. Analogies to 1933 Germany and the rise of Hitler abound. They seem to forget that Hitler was appointed chancellor, not elected (that’s indirect democracy at work), rose to power in a proportional voting system based on party lists (the preferred mode of political scientists), led a coalition government (again, as recommended by political scientists), and had the support of many of the country’s leading professors, 51 of whom signed an open letter advocating his appointment. Those mass rallies at Nuremberg made for powerful cinematography, but, when it came to the ballot box, Hitler was no Trump.

Despite 200 years of repeated warnings, there is still democracy in America. What prevents the US, the UK and other Anglo-Saxon democracies from falling into French Revolutionary anarchy or German Nazi fascism (or, for that matter, Russian Soviet communism) is a deep philosophical commitment to liberty. Not the meagre liberty from oppression of Robespierre’s ‘Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité’, but the buoyant liberty of action of Jefferson’s ‘Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness’. In a well-founded, well-functioning democracy, liberty is not some kind of necessary evil, as imagined by Tocqueville. It is a positive virtue. Liberty is the lifeblood of democracy.

Liberty and the majority

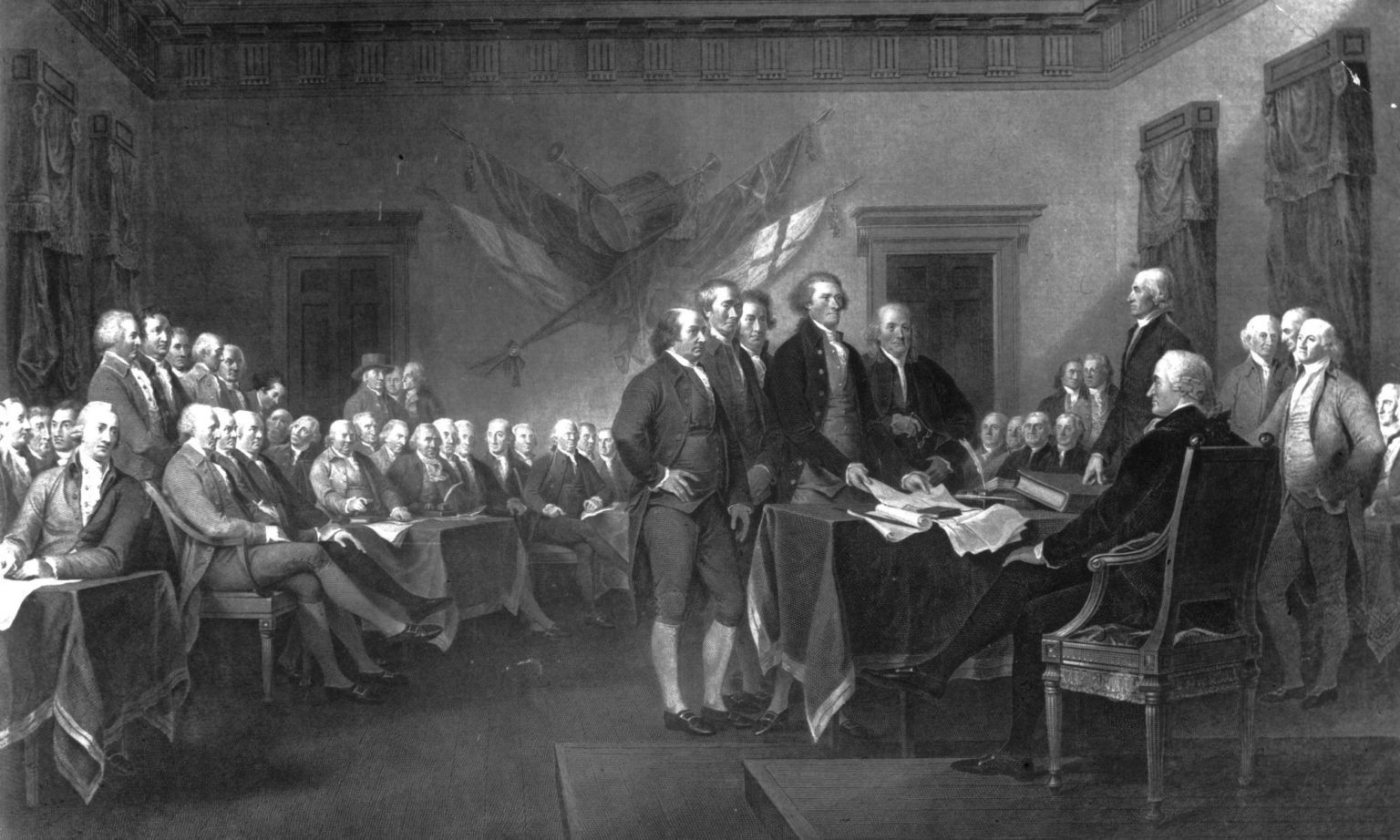

Alexis de Tocqueville did not coin the phrase ‘the tyranny of the majority’. The honour seems to go to the American founding father John Adams, who beat Tocqueville to it by nearly half a century. In his 1787 Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America, he wrote that in a ‘simple’ democracy there was ‘no possible way of defending the minority… from the tyranny of the majority, but by giving the former a negative on the latter’, an idea that he called ‘the most absurd institution that ever took place among men’. He pointed to the liberum veto in 18th-century Poland, by which any member of the Sejm (the lower house of the Polish parliament) could obstruct any bill from passing, as bringing ‘ruin to that noble but ill-constituted republic’.

Adams’ solution to the tyranny of the majority, echoed 48 years later by Tocqueville, was a mixed government of three branches: legislative, executive and judicial. Over the years, the idea that the separation of powers among three branches of government ensures the stability of democracy has become a principle of faith among political scientists, despite the fact that there is little evidence to support it. Many countries with ideal constitutions have fallen prey to Tocqueville’s aggrieved minorities, while the UK, with its historical concentration of powers in parliament, has been a relative rock of stability.

The real solution to the tyranny of the majority in Anglo-American democracy has less to do with political science than with political sociology. Peoples who expect and demand personal liberty as their birthright are not liable to tolerate tyranny, whether of the majority or of the minority (or of the one). And thus the US, a country founded by people who believed that life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness were so fundamental that ‘whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it’, has had the same government for 230 years. The secret to democratic stability is, in one word, liberty.

Edmund Burke understood this more clearly than any of his contemporaries. In his magisterial Reflections on the Revolution in France, he described liberty as ‘an entailed inheritance derived to us from our forefathers, and to be transmitted to our posterity’. He traced the liberties of ‘Englishmen’, from the Magna Carta through the 1628 Petition of Right and 1689 Declaration of Right straight to the American Revolution. Liberty first, democracy second.

There are no such things as minority rights – or at least, there shouldn’t be

Where the English attachment to liberty came from, no one can say. Romantics like to trace it back to the Saxon tribes who flooded into Britain after the collapse of the Roman Empire. Back on the continent, Charlemagne, the Medieval king so beloved by Europhiles, had a tough time suppressing the liberties of the Saxons who remained behind. It took him 32 years, three invasions, and one massacre to subdue the Saxon tribes of northwestern Germany and forcibly convert them to Christianity.

The Magna Carta wasn’t the source of English liberties, but it was their first written formulation. Those liberties ultimately gave rise to some of the longest-lasting, most robust democracies of modern times. They were passed down intact from generation to generation for more than a thousand years. Jefferson called them ‘unalienable’; Burke called them ‘entailed’. They were common-law rights and freedoms that could not be traded away. Under the English monarchy, they shielded the individual from the tyranny of the king. In a modern democracy, they shield the individual from the tyranny of the majority.

The minority of one

There are no permanent majorities or minorities. Individual people are sometimes in the majority and sometimes in a minority, depending on the issue. In the US, an African-American Christian heterosexual homeowner is once a minority and three times a majority. Change ‘Christian’ to ‘Pentecostal’, and the same person’s religion flips from majority to minority. American whites are a majority, but only because over the years various ethnic groups, including Irish, Italians, Eastern European Jews, Greeks, Georgians, Armenians, Finns, and Slavs of all kinds have come to be redefined as white. Contrary to the demographers’ predictions, the US will never be a ‘majority-minority’ society, because minorities keep joining the majority, generation after generation.

But there is one minority that will never disappear: the minority of one. Each of us embodies a multiple intersection of affinities that makes us unique. That may seem platitudinously obvious, but it is too often forgotten when people talk about ‘minority rights’. There are no such things as minority rights – or at least, there shouldn’t be. Adams and Tocqueville, the very writers who introduced the ‘tyranny of the majority’, both recognised that it was even worse to give special rights to a minority. The greatest assurance of the lives, liberty, and property of the members of any minority group is for society to hold fast to a tradition of individual liberty for all.

Adams almost reached that conclusion when he admitted that ‘the people are the best keepers of their own liberties, and the only keepers who can be always trusted’, but he thought that this principle would not work in a representative democracy. Tocqueville, too, danced around but never quite arrived at the conclusion that, when it comes to maintaining a healthy democracy, society is more important than the state. It was left to John Stuart Mill to grasp fully the reality that individual liberty is the prophylactic that safeguards society from the tyranny of the majority.

In On Liberty (1859), Mill took it for granted that the limitation of ‘the power of government over individuals’ was necessary to prevent the tyranny of the majority. He also understood that, in England at least, there was ‘a considerable amount of feeling ready to be called forth against any attempt of the law to control individuals in things in which they have not hitherto been accustomed to be controlled by it’. Like Tocqueville, Mill worried that the coercive power of society was much greater and more fearsome than the coercive power of the state; indeed, he thought it was capable of ‘enslaving the soul itself’. But society doesn’t deprive you of life, liberty, or property when you break its rules.

Governments do. Individual members of minority groups who feel oppressed by everyday microaggressions, dehumanised by other people’s opposition to their opinions, or terrified by facts that might trigger their memory of historical trauma, might pause a moment to reflect on the implications of seeking redress through the law. If they live in an Anglo-American democracy, they would be asking the government to override age-old common-law liberties in favour of their own interests. That’s about as dangerous as it gets.

For if a minority can use the machinery of government to control behaviour it finds offensive, it is difficult to see how a majority can be prevented from doing the same. Everyone is offended by something. Construe an issue as a matter of minority rights, and it can only be won by subverting democracy. Construe it as matter of individual rights, and… well, everyone is an individual. The legitimacy of liberal democracy rests on the principle that every individual citizen enjoys the same rights and freedoms – and the same interest in defending them. Liberty first, democracy second. When everyone is in the same minority of one, there is safety in numbers. That’s why, in a well-functioning liberal democracy, minorities don’t have any rights. Only individuals do.

Salvatore Babones is an associate professor of sociology at the University of Sydney, and the author of The New Authoritarianism: Trump, Populism and the Tyranny of Experts, published by Polity Press. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.