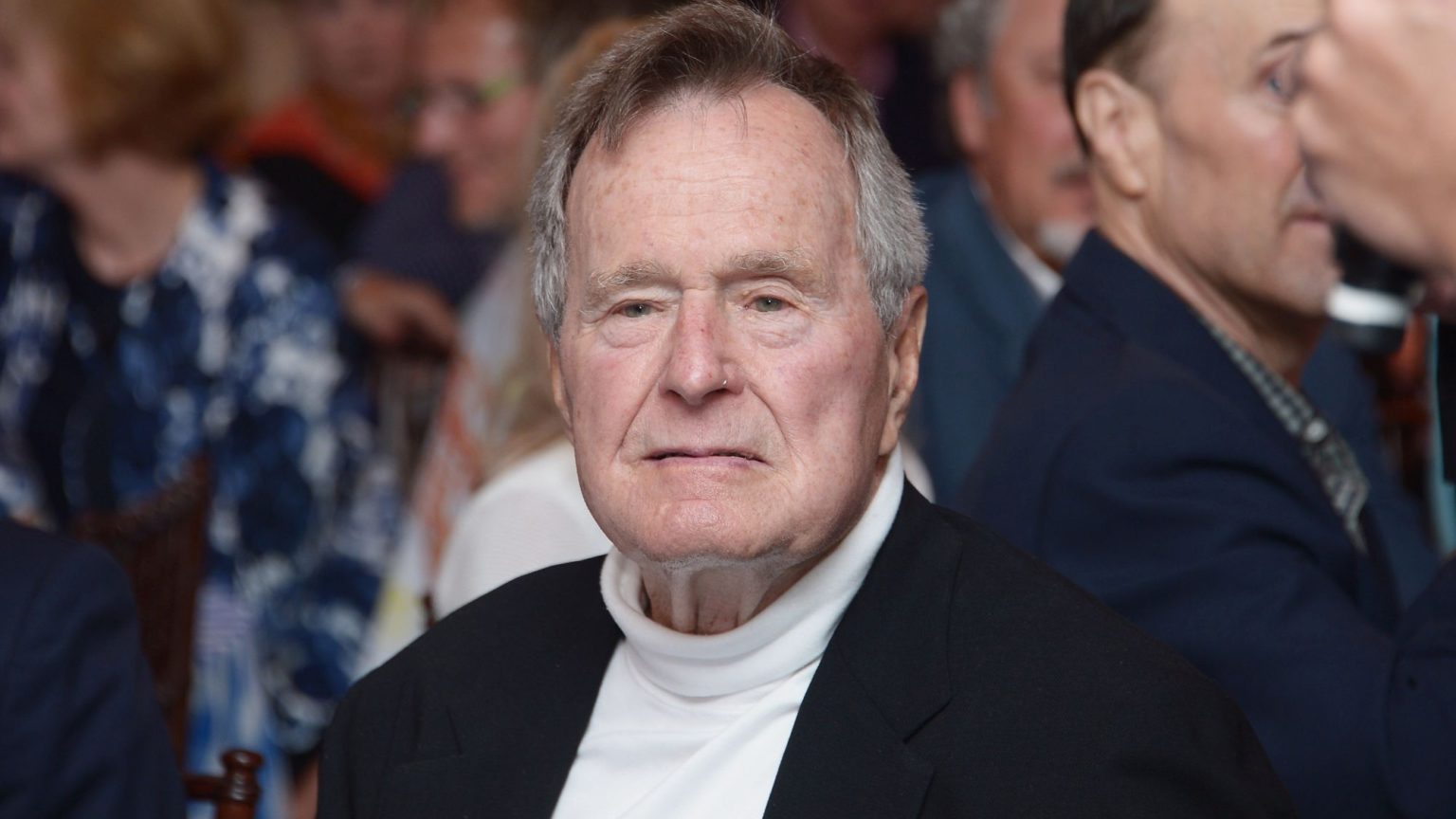

The caretaker president

George HW Bush embodied a post-Cold War elite that had run out of steam.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

George Herbert Walker Bush’s one-term presidency, from 1989 to 1993, might best be captured by his bewildered, low-key assessment of the fall of the Berlin Wall: ‘It clearly is a good development in terms of human rights… I’m very pleased with this development.’ When a reporter asked why he was not more enthusiastic, Bush responded unconvincingly: ‘I’m elated, I’m just not an emotional kind of guy.’

The flood of pre-written obituaries about the 94-year-old Republican, who died at his home in Houston on Friday, offers only a mediocre assessment of his presidency. Writers praise his foreign policy, but note his inattention to domestic issues and inept campaigning in the 1992 election.

In truth, Bush’s inarticulate and indecisive style reflected the crisis within an elite that had run out of steam and sorely missed the certainties of the Cold War. Bush famously lacked, as he himself admitted, the ‘vision thing’, as did the entire establishment at the time.

Bush, one of only 10 one-term presidents, is unlikely to sink to the ignominy of Gerald Ford or Andrew Johnson. But he is equally unlikely to achieve the posthumous admiration enjoyed by Harry S Truman. Following Ronald Reagan, who energised the Republican Party in the way that JFK energised liberals, was never going to be an easy task. Bush’s job was to draw back from the radicalism of the Reagan years, to reassert the status quo’s moderation. As one unflattering biography noted, Bush was a do-nothing president with no real national priorities. He was a custodian rather than a leader.

Bush was born into an old, established, Yankee family. He was the 5th generation of his family to attend Yale University. He even had an ancestor named Obediah Bush. A life of incredible privilege came with access to politics. But service, too, was expected. George fought bravely as a pilot in the Second World War.

Bush became a millionaire by the age of 40 through investing in oil in 1960s Texas. He was elected to the House of Representatives in 1966. In 1970, he eyed a seat in the Senate, but lost. He was given patronage positions by the Nixon administration until he stood for the presidency against Ronald Reagan, and lost again. But Reagan needed a moderate on his ticket and asked Bush to be his vice-presidential pick.

Bush’s personality – that of a pushover dad trying to keep order at a teenager’s party – oddly suited the presidency in the years between Reagan and Clinton. But he was lambasted for it. He was famously called a ‘wimp’ by Newsweek. As cartoonist Garry Trudeau’s ‘Doonesbury’ comic strip acerbically observed, Bush ‘put his manhood in a blind trust’.

However, a crack team of political advisers, unafraid of negative campaigning, reworked his image in time for the 1988 presidential election. On the campaign trail, Bush raised the spectre of Willie Horton, a black prisoner in Massachusetts, who, while released on a furlough programme, raped a white woman and bound and stabbed her boyfriend. Bush’s Democratic opponent was Michael Dukakis, then governor of Massachusetts, who Bush accused of being lenient on crime. Garry Trudeau accordingly created ‘Skippy’, Bush’s evil twin who emerged on the campaign trail.

Foreign policy shaped Bush’s presidency from the off. He inherited the Noriega crisis in Panama. Five months after his inauguration, China began its suppression of its pro-democracy movement. (He responded cautiously to the bloody crackdown on demonstrators in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square.) Five months after that, Bush looked bewildered at the fall of the Berlin Wall.

His successful foreign venture – the Gulf War – made him, briefly, incredibly popular. But this was already beginning to ease when he famously vomited into the lap of the Japanese prime minister in January 1992.

Bush’s domestic policy, like his infamous broken promise not to raise taxes, doomed his prospects of re-election. In 1992, recession loomed and the high approval ratings he enjoyed during the Gulf War disappeared. The entire Republican Party seemed divided and confused at the time. The Moral Majority that had helped Reagan to the presidency faded into obscurity. Opposition to abortion no longer united the GOP, and the end of the Cold War denied it a clear sense of purpose on the world’s stage.

By a margin of 43 per cent to 37 per cent, Democratic presidential candidate Bill Clinton, who had little experience in foreign affairs, beat Bush in the 1992 presidential race. Third-party candidate Ross Perot took 19 per cent of the vote. No third-party candidate had performed as well since Theodore Roosevelt, which gives you some idea of the crisis at the time.

How will history remember Bush? He was, at best, a bookend to the Cold War. He wasn’t the worst president, but nowhere near the best. Bush was the last of a generation of postwar presidents like John F Kennedy, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, whose conduct in the world was guided by anti-Communism. He was a product of a ‘liberal’ consensus in which everyone – Republicans and Democrats – accepted the so-called rules-based order.

Bush lived long enough not only to see his son, George W Bush, become president, but also to experience the backlash against the establishment embodied in the rise of Donald Trump. He even felt the wrath of the #MeToo movement: he was accused by eight women of touching them inappropriately, mostly while he was stuck in a wheelchair. He expressed the same bewilderment to these accusations as he had to fall of the Berlin Wall.

In the end, Bush’s commitment to the American establishment was stronger than his commitment to the GOP. He apparently voted for Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential election, so horrified was he by the ‘blowhard’ Trump.

Kevin Yuill is author of Richard Nixon and the Rise of Affirmative Action: The Pursuit of Racial Equality in an Era of Limits (Rowman and littlefield, 2006). He is currently writing a book on the 1924 Immigration Act.

Picture by: Getty

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.