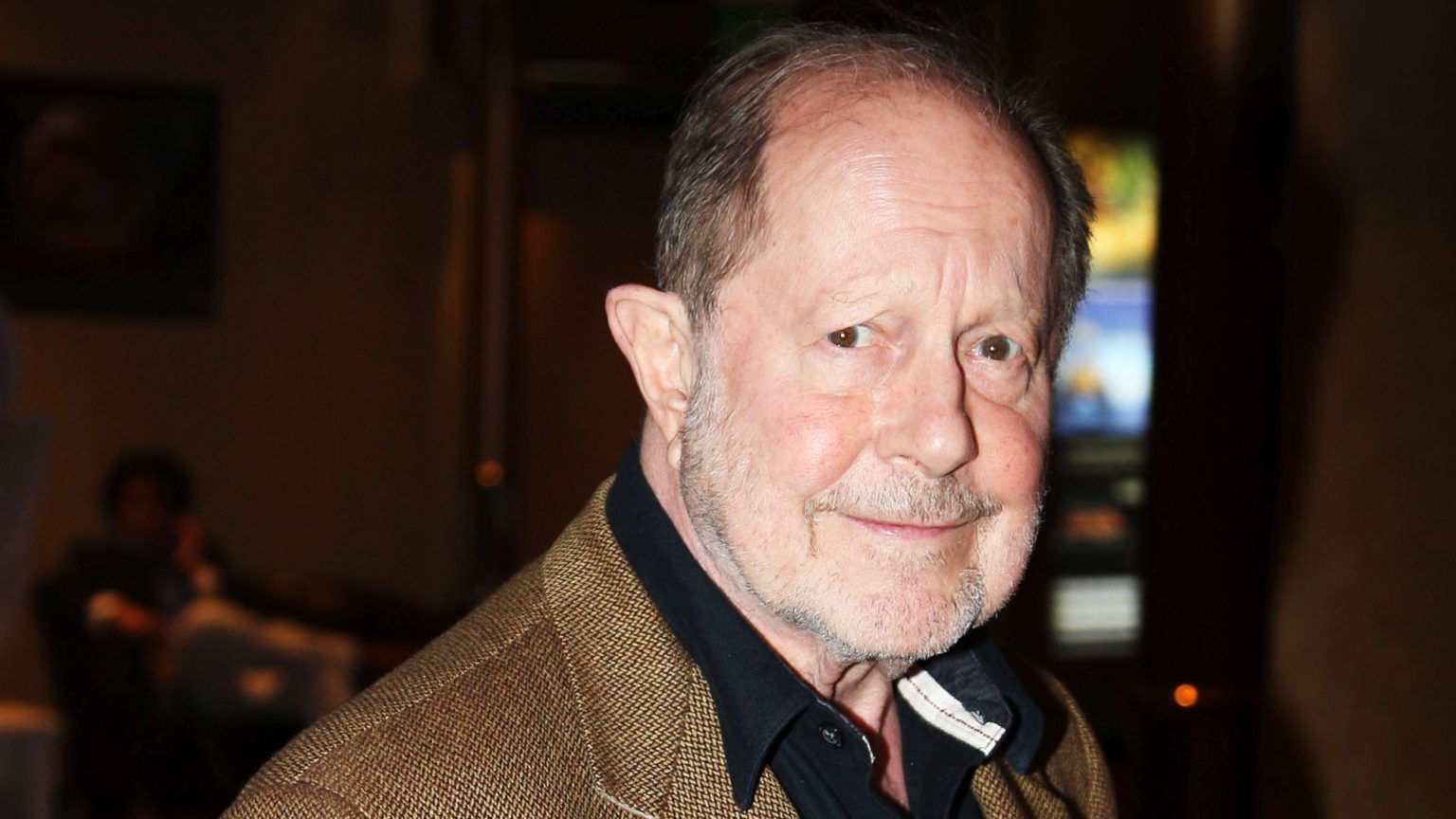

Roeg, the master of alienation

Nicolas Roeg’s painterly, sinister films had a profound impact on cinema.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

As a teen growing up in 1970s Britain, I was obsessed with David Bowie. I loved the legendary awkward live TV interview he did on The Russell Harty Show in 1975 in which he talked about his first major film role – an alien from outer space in a movie called The Man Who Fell to Earth. I couldn’t contain my excitement, so when the film was released, in 1976, I got my older cousin to sneak me into my first-ever ‘X’ certificate movie, at the Odeon in Croydon.

I was 14 years old and the film blew my mind. It defied all my expectations of what a sci-fi film should be. It also confounded me. What I remembered most was the sex: it was violent, messy and surreal. Bowie with a gun, romping naked and shooting blanks at his lover, played by Candy Clark. I remember the cinematic beauty and camerawork, too. I had never seen anything like it. It was my first Nicolas Roeg movie.

Over the years, I saw many more films by Roeg, who died last week at the age of 90. Films like Walkabout (1971), probably the most harrowing film of what it might feel like to be completely alone and isolated, set in the Australian outback; Performance (1970), a trippy film featuring Mick Jagger in which psychedelic hallucination meets East End gangster violence; and Don’t Look Now (1973), notorious for its verisimilitude sex scene and its menacing sense of grief and loss.

My favourite of Roeg’s movies is Bad Timing (1980), with singer Art Garfunkel and actress Theresa Russell playing the lead roles. The film’s distributor, the Rank Organisation, described it as ‘a sick film made by sick people for sick people’. Russell plays a sexually liberated young woman, driven by pleasure, drugs and alcohol, yet also mentally unstable. Art Garfunkel is an academic psychoanalyst. Like Bowie and Jagger in Roeg’s other works, Garfunkel gives his character a detached, aloof quality. These male performers bring an alien, otherworldly and effete masculinity to Roeg’s pictures, in sharp contrast to the earthy, sexually charged female characters set against them.

Again, in Bad Timing, the sex is brutal and unsettling. But the genius of the film is how past and present manically jump about, through brilliant editing, right from the opening scene of Russell being rushed to hospital in a coma following a drug-and-booze-fuelled attempted suicide. Her lifeless body is reduced to human meat as the medics perform a tracheotomy and vaginal swabs, attempting to piece together what happened to her, and to save her life.

The film flashes back and forth, from vivid Viennese interiors to sensual abandonment in Morocco. It depicts a tumultuous relationship of physical pleasure and sexual jealousy. Visual references to Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele paintings recur throughout, hinting at the sublime and visceral nature of sex and pleasure. It is disturbing in its voyeurism, drawing the viewer and other characters – including the policeman played by Harvey Keitel – into an uneasy complicit relationship with Russell’s ‘ravishment’.

Roeg’s visual aesthetic was painterly and stylish. Alienation, loss, loneliness, the fragility of desire – these were his themes which bore down upon his characters. His influence on cinema is profound.

Manick Govinda is programme director for SPACE and a freelance arts consultant. He writes here in a personal capacity.

Picture by: Getty

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.