Why aren’t we taking the Islamist threat seriously?

A slew of convictions should remind us that nihilism lurks in Britain.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

It’s been a long, hot summer – and a busy one for counterterror officials. While the prosecution of the suspect in the attempted car attack in Westminster this month is only starting to get underway, there have been a slew of terror trials and convictions that have quietly concluded these past few months.

On 31 May, Husnain Rashid, an Islamic State supporter from Lancashire, pleaded guilty to three counts of engaging in conduct in preparation of terrorist acts and one count of encouraging terrorism. He egged on other Islamists on the internet to attack Prince George, and had become a prolific pro-ISIS propagandist.

Five days later, 18-year-old Safaa Boular was found guilty of preparing for acts of terrorism. With her older sister Rizlaine and their mother Mina Dich (both of whom pleaded guilty to the same charges), she was planning a grenade and gun attack on the British Museum. In the end, the only glass ceiling she broke was in becoming the country’s youngest convicted female terrorist.

On 18 July, Naa’imur Rahman, 20, was convicted at the Old Bailey. Inspired by his jihadist uncle, Rahman had made contact with ‘ISIS recruiters’ who turned out to be FBI and MI5 agents. He asked them for a jacket and a rucksack stuffed with explosives. His plan was to blast his way into No10 Downing Street and behead the prime minister.

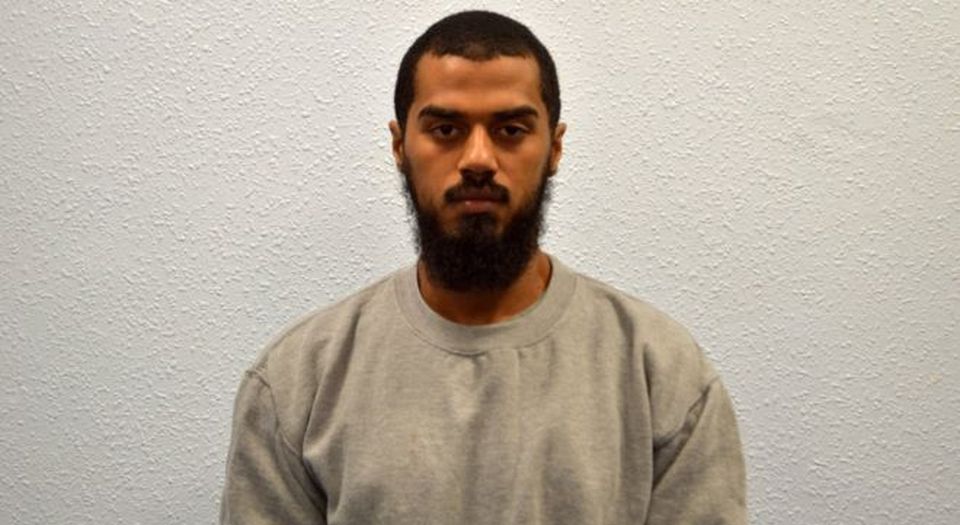

Two days after Rahman’s trial, Khalid Ali (pictured), 28, was handed three life sentences. He was apprehended in Parliament Square, just weeks after the 2017 Westminster Bridge attack, armed with knives. He had been on the police’s radar since he returned from Afghanistan, where he had spent five years making bombs for the Taliban.

Meanwhile, the trial continues of four men, believed to have Islamist links, who were arrested in December for plotting a Christmas bomb attack in Sheffield.

These plots were not all of the same scale or sophistication. While some of them came dangerously close to fruition, Rahman’s was clueless from the off. And Rashid’s main crime seems to have been crudely encouraging others to launch attacks, rather than launching any himself – a reminder of the blurry line between propaganda and incitement.

But what links these people is their hatred, their violent Islamist aspirations, whether or not they would ever actually have the bottle to follow through on them. Whatever the ins and outs of these convictions, they reveal that in 2017, the year of the attacks in Westminster Bridge, London Bridge and the Manchester Arena, some British citizens were inspired, rather than appalled, by those atrocities.

Islamist terror is not an existential threat to the West. But it is does pose serious moral and political questions; it demands a forthright response. Not least because a section of the West’s Muslim youth, though tiny and unrepresentative, is drawn to it.

According to recent estimates, 850 Britons have travelled to support or fight for jihadist groups in Syria and Iraq. ISIS’s most infamous executioners, The Beatles, were among them. Recent interviews with its two surviving members, Alexanda Kotey and El Shafee Elsheikh, who are awaiting extradition to the US, are chilling. They blankly, almost irritably, rebuff interviewers’ questions in unmistakable London accents.

Islamist nihilism lurks in Britain. And yet we seem incapable of discussing it openly. These cases and statistics are not suppressed, but they are downplayed, or relativised. Islamist extremism is increasingly held up as a threat among threats, comparable to that posed by the far right.

Mark Rowley, former head of the Metropolitan Police’s counterterrorism unit, said this month that the UK has not ‘woken up’ to the threat posed by the extreme right. The statement was swiftly leapt upon by commentators desperate to present Islamist terror as part of some general nebulous hatred, rather than a specific political ideology that has struck again and again in recent years.

We should, of course, take far-right violence seriously. Rowley notes that of the 14 plots foiled last year, four were neo-Nazi in nature. Indeed, another terror case that concluded this summer was that of Jack Renshaw, a member of the proscribed fascist group National Action, who pleaded guilty to plotting to murder Rosie Cooper, his local MP. It seemed almost a twisted tribute to the 2016 murder of MP Jo Cox, who was slain by the racist loner Thomas Mair.

But though far-right scumbags were responsible for just under a third of the foiled plots last year, they were also responsible for just one of the 35 people actually killed by terrorists on our streets.

Taking far-right extremism seriously doesn’t mean exaggerating the threat it poses. Small neo-Nazi grouplets and murderous racist loners are frankly not a comparable threat to a global jihadist movement actively recruiting and inciting British youth.

At its height, National Action was estimated to have 60 to 100 members. ISIS, at its height, controlled vast swathes of Syria and Iraq.

What’s more, throwing around the term ‘fascist’ as liberally as some now do is the opposite of taking the far right seriously. Recently, Labour shadow chancellor John McDonnell called for a new Anti-Nazi League. It was in response to Boris Johnson’s jibes about the niqab and burqa in the Daily Telegraph and the ransacking of Bookmarks, a socialist bookshop, by some Trump supporters.

And yet the best response many could muster after girls as young as eight were butchered at Manchester Arena was a dirge of ‘Don’t Look Back in Anger’.

Last June, in the wake of the London Bridge attack, in which three jihadists killed eight and injured 48 armed with 12-inch knives and a van, the prime minister, Theresa May, said it was time for some ‘difficult conversations’ about extremism.

A year later, and it feels like we have barely even started such a conversation.

Tom Slater is deputy editor at spiked. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Slater_

Picture by: Metropolitan Police

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.