Giving a green light to euthanasia

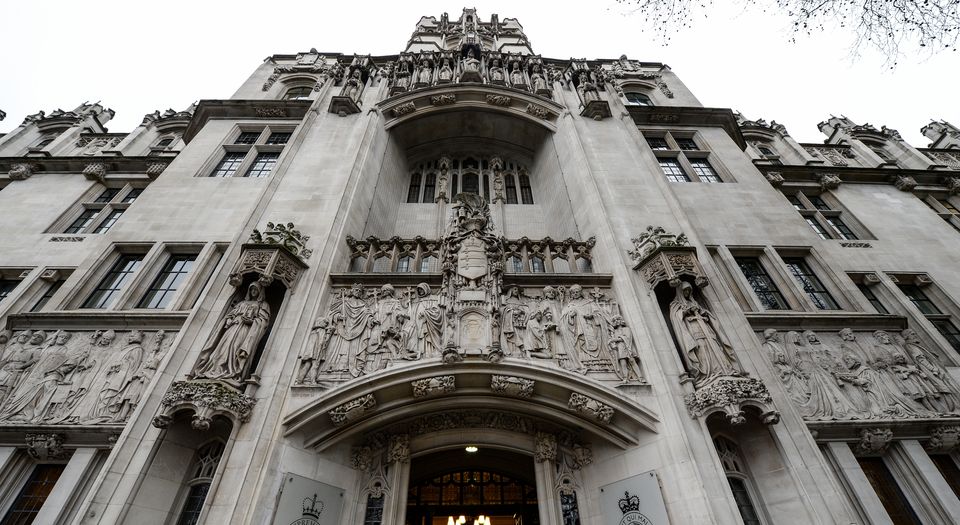

Why has the UK Supreme Court backed out of life-and-death decisions?

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

There was an important ruling in the UK Supreme Court this month. It struck down the mandatory requirement for hospitals to involve the court before withdrawing assisted nutrition and hydration from patients with a prolonged disorder of consciousness. That is, the court no longer has to be consulted when certain comatose people have their sustenance withdrawn and are therefore made to die.

The court essentially agreed with a recent judgement made by the Court of Protection. In that case, Briggs v Briggs, the treating clinician thought it would be unethical to withdraw treatment from a patient whose level of consciousness might improve over time. The Court of Protection ruled against the clinician. The judge, Charles J, emphasised the importance of finding out what the patient would have wanted in his or her current situation and said that if this ‘can be ascertained with sufficient certainty it should generally prevail over the very strong presumption in favour of preserving life’. The Supreme Court now agrees with this.

A Rubicon, whereby courts no longer have to be consulted before clinically assisted nutrition is withdrawn, has been crossed with the Supreme Court judgement. And this is despite the fact that there were questionable elements to the Briggs case. After all, who could ascertain what the patient wanted? Why would the judge assume that the patient would not change his or her mind about wanting to live and find a way to adjust to his or her changed circumstances?

The Supreme Court case – An NHS Trust v Y – confirmed that an act of killing can be made without court oversight. The case involved Mr Y, a 52-year-old banker, who had a cardiac arrest in June 2017. Mr Y, despite working long hours in a stressful profession, skied, ran, regularly went to the gym, and was said to have loved music and rock concerts. He had not left a living will or any instructions on what should happen to him in the case of sudden illness.

After the cardiac arrest, his physician declared him to be suffering from a prolonged disorder of consciousness, and said that, even if he were to regain consciousness, he would have profound cognitive and physical disability, remaining dependent on others to care for him for the rest of his life. Another consultant neurologist declared it improbable that he would regain consciousness. His wife, their two children and his brother and sister, the Supreme Court had previously heard, all accepted Mr Y would not want to live in a vegetative or minimally conscious state with profound disabilities. His doctors agreed.

Natalie Koussa, a director at the charity Compassion in Dying, a sister organisation to the pro-assisted suicide campaign group Dignity in Dying, welcomed the decision. She said it ‘recognises the fact that sometimes, sadly, it is in someone’s best interests to withdraw treatment. It will allow those closest to a person – their loved ones and medical team – to feel supported and empowered to make the right decision for the person, even when it is a difficult one.’

‘Withdraw treatment’? This is a euphemism for purposefully bringing about the death of a patient. A comatose patient is helpless, the definition of a ‘vulnerable individual’. Not giving a helpless individual food and drink is not simply ‘terminating treatment’ – it is essentially killing the patient, just as surely as not feeding a child would be killing. It is right, surely, that such cases should be decided in court and that decisions to kill patients should not simply be left to medics and family.

The judgement flies in the face of available evidence. The nightmare scenario for many people is ‘locked-in syndrome’ – being helplessly trapped within one’s body, unable to communicate. But many recover. Research at London’s Royal Hospital for Neuro-Disability found that nearly a fifth of the patients studied who were thought to be in ‘irreversible’ comas eventually woke; many remembered being conscious of what was going on around them, but were unable to communicate their wishes.

What’s more, few with locked-in syndrome agree with euthanasia campaigner Tony Nicklinson that continued existence is ‘miserable, demeaning and undignified’. Studies of patients suggest that while the layman imagines it a fate worse than death, the vast majority of those who are locked-in want to stay alive. As Dr Mark Delargy, director of the brain-injury programme at the National Rehabilitation Hospital in Dublin, has noted: ‘The person has been in a state for so long that they have worked out how to cope with this. They have lived with the situation, day by day, until an appropriate person finds out… People who [have] locked-in syndrome say it isn’t great but it is better than being dead.’

In a study released last year by the Wyss Centre for Bio and Neuroengineering in Switzerland, which used a pioneering brain-computer interface that deciphered their thoughts, locked-in patients unable to move even their eyes told doctors they were ‘happy’. All of the patients studied owed their conditions to motor-neurone disease and had little chance of improvement in their condition.

There is no doubt that hopeless cases exist. But the facile willingness of the court to allow the killing of patients because they no longer enjoy skiing or attending rock concerts contrasts with the depth of determination and love of Toronto-based Martin Shapiro for his wife Annie, who awoke from her coma after nearly 30 years. Annie was watching the news of the assassination of President Kennedy in 1963 when she collapsed at age 50, suffering a massive stroke. For two years she was totally paralysed, her eyes staring wide open. Steel-foundry worker Martin placed drops in her eyes every few hours. For nearly 30 years he refused to give up on her. He fed and dressed her every day. He slept every night beside her. On 14 October 1992, she suddenly snapped out of her coma, telling Martin to turn on I Love Lucy. She was shocked to see Martin’s grandfatherly appearance – he was now aged 81.

Martin, who had refused to place his wife in a nursing home, explained in a TV interview: ‘When I made my vows and promised to stay together in sickness and health, I meant it.’ The couple were able to rekindle their romance. ‘We could both hardly walk but Annie wanted me to take her dancing.’ Life can continue, even in the hardest of circumstances. Does the Supreme Court not understand that?

Kevin Yuill teaches American studies at the University of Sunderland. His book, Assisted Suicide: The Liberal, Humanist Case Against Legalisation, is published by Palgrave Macmillan. (Buy this book from Amazon (UK).)

Picture by: Wikimedia Commons

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.