Frida Kahlo: art trumps identity

She may be an icon – but it’s time to recognise her as a great artist, too.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up, the new exhibition at the V&A London, examines Kahlo’s private world, displaying paintings, drawings, photographs and private possessions to form a powerful presentation of Kahlo the artist and the woman.

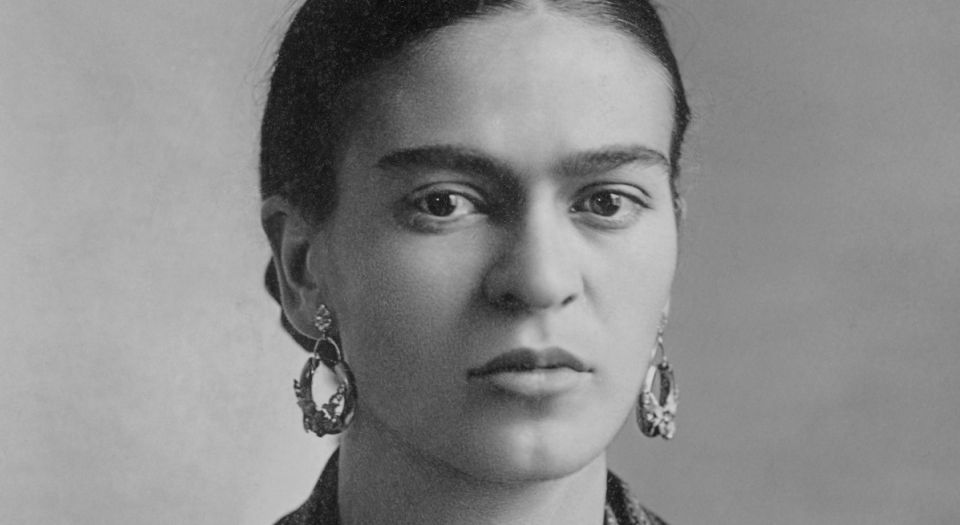

Such an approach might seem intrusive. Yet Kahlo (1907-1954), one of the most famous painters of the 20th century, was an artist uniquely concerned with her self, displaying it in its various guises. Her symbolic portraits and self-portraits – combining Surrealism, Mexican painting and naive amateur art – and her personal life – her precarious health, commitment to Communism and tempestuous marriage to famed muralist Diego Rivera – all flowed into what is a strikingly autobiographical artistic enterprise, rich in allusion and metaphor. Indeed, fascination with her autobiography, combined with acclaim for her art, propelled Kahlo to stardom long after her death, spawning films, documentaries and numerous books.

Making Her Self Up makes use of the treasure trove of private items belonging to Kahlo discovered in 2003 in a sealed room at Casa Azul, her house in Mexico City. It includes letters, drawings, medicines, clothing and 6,500 photographs, giving a yet more intimate insight into her life. With a Kahlo exhibition, there is always a danger it will turn into little more than autobiography, but the curators here have struck the right balance between art and life.

One of the catalogue essayists notes that Kahlo was already adept at changing her image radically and acting out different roles for the camera before she began painting. Kahlo would present herself as a woman in traditional Mexican lace collar and shawl, an androgynous figure in slacks and slicked-down hair, or an indigenous peasant with an Aztec stone necklace. Her wardrobe consisted of manufactured American, European and Mexican clothing, and garments the artist herself made. Kahlo felt a particular attachment to the traditional dress of the indigenous Zapotec people of Oaxaca region. The bold designs and strong colours became the artist’s sartorial trademark. Kahlo wore long skirts to cover a leg shortened by a bout of childhood polio. On display at the V&A is a pair of boots, one with a built-up sole.

A 1925 life-threatening tram accident left her with permanent injuries, causing her to be bedridden for long periods. Bottles of medicine and discoloured surgical corsets (one adorned with a hammer and sickle) are a sobering reminder of the crudity of the surgery, physiotherapy and medication of Kahlo’s time. She painted herself wearing the corsets, equating them to torture devices. (She underwent more than 30 operations in her lifetime.) Ultimately, medical intervention sustained her ravaged body until the age of 47. The juxtaposition of suffering and glamour is one of the most distinctive aspects of Kahlo’s biography.

Along with perfume bottles (Chanel No5) are cosmetic products of the 1940s and 1950s. The powder compacts, lipstick and nail polish (most of American manufacture) are of the hottest colours. Kahlo chose not to pluck her famously heavy eyebrows, countering the norms of the day. However, a significant number of other young Mexican women did the same – so the act is not as rebellious as is sometimes assumed. It seems to have been an assertion of preference more than a coded social stance.

Kahlo was not well known as a painter during her lifetime, although she exhibited and commanded respect from colleagues. She was principally recognised in public as the wife of Diego Rivera, a superstar in Mexico, known for his murals and political activism. Her exotic looks and individual style attracted much attention, even generating comment in newspaper articles. Jewellery was important to Kahlo and she wore a lot of it, from vintage colonial necklaces and pre-Columbian stone bracelets to outsize silver rings. Examples here include secondhand-store finds, carved jade and pieces made specifically for her.

Kahlo’s appearance has become iconic – part traditional Mexican, part thrift-store hipster. ‘The links to Kahlo’s heritage and political beliefs have been superseded by her beatification’, one writer notes in the exhibition catalogue. True enough, but it is equally true that politically motivated art historians have been busy colonising Kahlo, turning her into a feminist icon. She never demanded or expected to have her art accepted because she was a victim or survivor; rather, she aspired to have it accepted because she had painted her pictures sufficiently well.

Throughout her life, Kahlo was a public supporter of Communism. But it seems reasonable to think that this was born more from her emotional solidarity with the poor of Mexico than any love for Stalinism and its Socialist Realist credo. Her closeness to Trotsky (with whom she is rumoured to have had an affair while he stayed at Casa Azul) may have made her feel there was a more humane alternative to Stalinism within the spectrum of Socialism.

A curator states, ‘it is her construction of identity through her ethnicity, her disability, her political beliefs and her art that makes her such a compelling and relevant icon today’. Up to a point, yes. But the crucial point is that none of the preceding would be of interest to anyone if her art was not outstandingly good. And it is. Kahlo should be an example and a warning to every art student today. She demonstrates that artists can put into their art as much politics, personal experiences and socio-cultural commentary as they want, but that their art will only survive – and even become revered – if it is good enough. If the art is good, it will endure. If the art is not good, no amount of autobiography and identity politics will compel viewers to value it.

Alexander Adams is an artist and writer. His website is here.

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up is at the V&A London until 4 November 2018.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.