Long-read

A revolution of feeling

Rachel Hewitt’s history of emotion explores the late-Enlightenment mind

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Have you ever described yourself as being ‘pent up with anger’, ‘about to blow’, or ‘pumping with energy’? You may not know it, but the vocabulary you are using is borrowed from the hydraulic theory of the late Enlightenment period.

This is just one of the fascinating insights provided by Rachel Hewitt in her new book, A Revolution of Feeling: The Decade that Forged the Modern Mind. She contends that ‘like ideas, our emotions have a history’. And investigating the Enlightenment-era change in approach to what were then called the passions ‘presents a novel and startling way of seeing, or feeling, political change’.

A Revolution of Feeling takes a brief but important moment in British history – the last decade of the 18th century – and, in rich, fascinating detail, explains how a radical change in political sentiment was linked to an equally abrupt change in attitudes to emotions. The disappointments of the French Revolution, the foiled uprising in Ireland and the violent turn against radical politics in England left many British radicals feeling without hope. As Hewitt puts it, during the 1790s, radicals witnessed not only the disappearance of the prospect of revolution in Britain, but a ‘turn to individualism, pessimism, caution and conservatism in attitudes to emotion, and its divorce from politics’.

Before the 1790s, Hewitt argues, ‘passion’s significance was predominantly social, and political reform was thought to proceed hand in hand with emotional reform’. Emotion and sentiment were therefore drivers and expressions of political desire. By the early 1800s, emotion had ‘been progressively stripped of its cognitive role – its role in learning and education – its sensitivity to inequalities and deprivations in the material world, and its part in making judgements about the propriety of investment and attachment’. Emotion was no longer intrinsically linked to political fervour – it was random, and often seen as meaningless.

Hewitt begins her account of this revolution in feeling in November 1791, at a dinner party hosted by Joseph Johnson, then London’s most famous literary critic. Among those in attendance were Mary Wollstonecraft, her future husband William Godwin, and Thomas Paine. But what happened at the dinner party is not revealed until 14 pages later (Godwin left dismayed that he had spent the evening talking to a brazen Wollstonecraft, rather than charming his way into a friendship with Paine). Before that revelation, Hewitt speeds us through a potted history of the English reform movement during the 18th century, including the imprisonment of John Wilkes, and the rule of William Pitt the Younger, who was initially sympathetic to the cause of political and electoral reform. Hewitt also details the events leading up to the storming of the Bastille in 1789, and how the use of emotion was directly linked to the expression of revolutionary political demands. Focusing on Jacques-Louis David’s unfinished painting, The Tennis Court Oath (1790-94), which depicted the incipient National Assembly’s pledge in 1789 to refuse to be disbanded until a new French constitution had been adopted, Hewitt explains how ‘raw emotion impelled every member of the National Assembly into free, expansive gestures, illuminated by a brilliant shaft of light – or lightening – and refreshed by a gust of stormy but pure air blowing in from the West: from America, whose own revolution had been concluded just six years previous’.

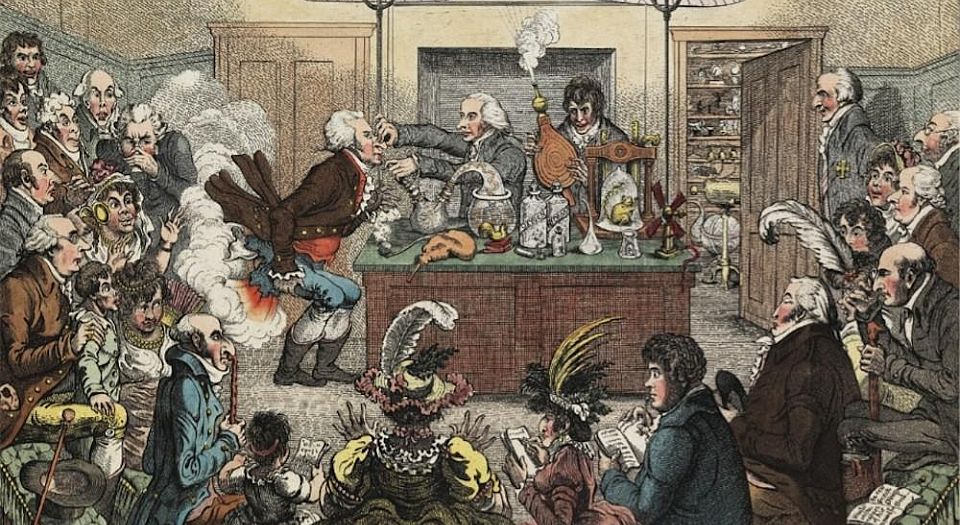

Much of A Revolution of Feeling is written in this way. Beginning with the intimate details – meetings, letters, relationships and journeys – of a handful of key British thinkers, Hewitt then launches into vast and tangential detail about the historical context of the time. It makes for a truly compelling read. Take Hewitt’s description of the reaction to the discovery that nitrous oxide gave people the giggles, when delivered out of what became known as the ‘excellent airbag’. As she notes, it reveals how desperate many of the English, Enlightenment-inspired thinkers were to direct emotions towards political ends. If pain and sadness could be eradicated, political instability would become less likely.

At the heart of Hewitt’s exploration into this revolution of sentiment are two radical figures: Mary Wollstonecraft and the academic, and quasi-scientist, Thomas Beddoes. The French Revolution serves as the backdrop to their personal stories, sometimes directly affecting their decisions, but more often informing their outlook on political events in England. While Beddoes spends the final years of the 1700s in between Bristol and Oxford, maintaining various projects and being constantly accused of Jacobinism, Wollstonecraft travels across Europe, spending a period of time in Paris at the height of the so-called Reign of Terror.

One morning, Wollstonecraft witnessed the Sun King, Louis XVI, walk past her window on his way to trial. The day passed without bloodshed, and Wollstonecraft wrote to her friend and dinner-party host Johnson: ‘For the first time since I entered France I bowed to the majesty of the people, and respected the propriety of behaviour, so perfectly in unison with my own feelings.’ Wollstonecraft’s relief was understandable. The mass guillotining in Paris had turned the stomachs of many hopeful English radicals. They may have supported the idea of a French Republic, but wished that the revolutionaries would exercise some restraint in making the idea a reality. In this regard, Wollstonecraft was typical. She had initially been glad of the respite she found in Paris, having fled London and the embarrassment of having her romantic aspirations rejected by the dapper painter Henry Fuseli. But as the bloody reality of the revolution became apparent, she began to suffer from nightmares, writing of ‘eyes glar[ing] through a glass door opposite my chair, and bloody hands [shaking] at me’. She wrote to Johnson that ‘I want to see something alive’. As it became clear that English émigrés living in Paris were no longer welcome, Wollstonecraft escaped to the countryside, and into the arms of an American philanderer by the name of Gilbert Imlay.

This in some ways is what makes A Revolution in Feeling a truly remarkable achievement: the ability to convey the intricate relationship between the broader historical movements of the era and the changes in the particular feelings of an individual, in this case, Wollstonecraft.

For Beddoes, the effects of the Revolution were just as acute. William Pitt the Younger, previously sympathetic to reform, used the threat of Jacobinism and the fear of the French Revolution to crack down on freedom of the press and freedom of association in England. Hewitt gives an incredibly informative history of the so-called ‘gagging acts’, including the Seditious Meetings Act (1795) and the Treasonable and Seditious Practices Act (1795). Beddoes and other English writers, who flirted with Jacobinism, spoke out against this illiberal turn in British politics. They hoped that the more Pitt cracked down on political freedom, the more likely it was that some insurrection would be mounted on English soil. Hewitt shows how this belief that political repression would lead to a burst of revolution was in line with the prevailing hydraulic theory of emotions. Pent-up political resentment would thus result in a burst of new and exciting radicalism.

It wasn’t to be. In fact, the 1790s were marked less by political excitement than the dampening of any revolutionary enthusiasm. With the French Revolution increasingly serving as an example of how great hopes could turn into an actual nightmare, there was little room for Beddoes and others to discuss the prospect of a different political settlement without being labelled traitors and menaces to English society, and punished accordingly.

Hewitt is most interested in the effect the events of the late 18th century, and the changing view of the passions, had on the discussion of women’s rights and sexual freedom. Wollstonecraft’s own transition from her sentimental past to the cool rationality expressed in her most famous work, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, is crucial to understanding the link between emotions and politics. Wollstonecraft entreats her fellow females to ‘excuse me, if I treat them like rational creatures, instead of flattering their fascinating graces, and viewing them as if they were in a state of perpetual childhood, unable to stand alone’. Her demand that women be better educated, and thus ‘endeavour to acquire strength, both of mind and body’, got her into hot water. But Wollstonecraft was writing at a time when debate about the virtues of marriage, the difference in emotion and feeling between men and women and the right way to organise society, were up for discussion (albeit a discussion held among men). Hewitt notes that the legalisation of divorce by the Legislative Assembly of the French Republic, combined with the philosophical investigation of rationality and reason within the Enlightenment period, opened a tiny space for someone like Wollstonecraft to ask a key question: ‘Who made man the exclusive judge, if women partake with him the gift of reason?’

However, while A Vindication of the Rights of Woman was successful, Wollstonecraft’s personal life was less so. She had had a child with Imlay – her beloved Fanny (‘Fannikins’). Then, after many unreturned letters of unrequited love, it became clear that Imlay had begun a romance with someone else. Hewitt writes that Wollstonecraft ‘found herself exposed to the great lie of the sexual free market: the myth that it set everyone free’. After realising that ‘her female body had born the consequences of the liberation of male desire’, she realised how isolated she had become from polite society. Few would socialise with a woman so tainted by intrigue and political subversion, and now with a child born out of wedlock. In 1795, Wollstonecraft threw herself off Putney Bridge. Hewitt’s description of the event is chilling. ‘When she did not sink, Wollstonecraft gathered her clothes tighter, bunching herself into a small dense weight.’ But try as she might, she could not kill herself, and was pulled unconscious out of the water, and then resuscitated by a passing boatman.

After this failed suicide attempt, in 1796 Wollstonecraft re-encountered Godwin, and the following year they married. Hewitt spends many of the subsequent chapters joyfully tracing the development of their union and marriage – a union that confused many at the time, as both Wollstonecraft and Godwin had criticised the political limitations of matrimony.

Wollstonecraft died just a few months after marrying Godwin. But it was not at her own hand, but from the complications of giving birth to hers and Godwin’s daughter, Mary (who, following her marriage to Percy Bysshe Shelley, was to find her own fame as the author of Frankenstein). Godwin, distraught, decided to honour Wollstonecraft by publishing her memoirs in 1798. Hewitt, however, is scathing about Godwin’s attempts to characterise Wollstonecraft’s views on sentiment and politics. ‘[His] eulogy’, she writes, ‘did a disservice to Wollstonecraft’s lifelong attempts to attain “virtue” by harmonising reason and emotion’. She also argues that ‘Godwin’s sexually explicit revelations [about Wollstonecraft] were also responsible for ensuring that [she] became a cultural figure of fear and loathing in the early 19th century, the nadir against which feminine virtue was defined’. How ironic that a woman who sacrificed so much to argue for a woman’s right to be taken seriously came to be used as a cautionary tale for women attempting to aspire above their station.

Hewitt’s history of emotion is a depressing, albeit fascinating, one. ‘In 1789, France had offered a beacon of hope for radical political change, but by the end of the 1790s it appeared a desperate disappointment to many British citizens’, she writes. Her chapter titles reflect the change in the emotional climate. The book begins with ‘Spirits Strong in Hope’, moving to ‘Hope Discouraged’, then ‘Disappointment Sore’, before ending with ‘The Age of Despair’.

But Hewitt’s real motive behind such extensive research into the relationship between emotion and politics does not become clear until the very final paragraphs of the book. She writes: ‘The trend towards the depoliticisation of emotion, and the heightened perception of emotion as an individual rather than a social phenomenon, discourages women from challenging the way in which emotions and emotional negotiations are infected with highly rendered inequalities of power.’ It is hard not to feel disappointed by this late feminist interjection. But this does little to diminish the force of this stimulating, and even radical history of the end of the Enlightenment period.

Hewitt argues that the 1790s was the decade that ‘forged the modern mind’. In many ways, this is true. The idea that views of women’s emotional differences to men have not changed seems a little dramatic. Yes, interesting similarities in the ‘hydraulic theory’ of emotion persist today, and much of the anxiety about the relationship between emotion and politics is undergoing a revival in the aftermath of Donald Trump’s election and Brexit. Even today’s hate-speech laws resemble to some extent the tyranny of Pitt’s gagging acts. Hewitt warns that ‘there is much to learn from the lost legacy of the 1790s’ philosophy of emotion… when the passions were collective political experiences and forces… and when revolutions were driven by feeling’. She could well be on to something.

Ella Whelan is a spiked columnist. She is the author of What Women Want: Fun, Freedom and an End to Feminism, published by Connor Court. Buy it on Amazon UK and Amazon US.

A Revolution of Feeling: The Decade that Forged the Modern Mind, by Rachel Hewitt, is published by Granta Books. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.