The problem with Kendrick Lamar winning the Pulitzer

It isn’t for high-culture awards judges to confer legitimacy on hip-hop.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

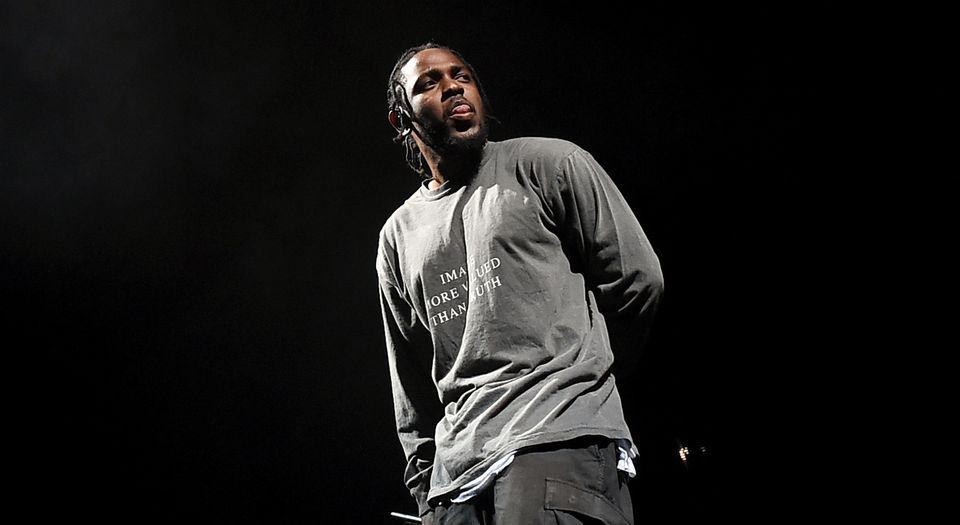

What do Michael Gilbertson, Ted Hearne and Kendrick Lamar have in common? All three were finalists for this year’s Pulitzer Prize for music. But only one of them is someone most of us will have heard of – and, spoiler alert, he’s the one who won.

The decision by the Pulitzer board to give hip-hop star Lamar the award for his blockbuster album DAMN., beating Gilbertson’s string quartet and Hearne’s cantata for chamber choir, has riled some in the classical-music world. But it has been met with almost uniform celebration elsewhere.

In fact, the feather-spitting protests from composers and critics, disgusted that this award, which has only recently started to recognise jazz, should celebrate mainstream rap, have been conspicuous by their absence – or, at least, more muted than we might have expected. The other finalists, incidentally, say they are delighted.

The Pulitzer board’s decision was similarly unanimous. After discussing a classical work that incorporated hip-hop elements, they decided to go to the source. It was suggested they listen to DAMN., Lamar’s double-platinum fourth LP. ‘We listened to it and there was zero dissent’, one board member told the New York Times.

The board’s excitement notwithstanding, their word-mangle justification for Kendrick’s unprecedented win did have a strong whiff of condescension and ignorance, calling DAMN. ‘a virtuosic song collection unified by its vernacular authenticity and rhythmic dynamism that offers affecting vignettes capturing the complexity of modern African-American life’.

Nevertheless, it has been hailed as a ‘big moment’ for hip-hop, and for black music in general. After all, the Pulitzer first recognised jazz as late as 1997, giving the prize to Wynton Marsalis’s oratorio ‘Blood on the Fields’ – which, not unlike DAMN., explored the darker parts of the black American experience. In 1965, Pulitzer jurors were blocked from giving a citation to Duke Ellington.

Many have compared it to the Nobel committee’s decision to honour Bob Dylan last year. Of course, Kendrick’s Pulitzer is less controversial by dint of the fact that this was, at least, a music award; Dylan, whose own forays into prose were sketchy at best, impenetrable at worst, became a Nobel laureate for literature, on the basis of words he only ever wrote to be sung.

But what both these moments do have in common is that it was the prize committees themselves who were pushing for them. Neither was a case of these pop icons banging on the doors of the old elite. They were invited in, and caught off guard. And just as Dylan remained silent for weeks after the Nobel announcement, Lamar has so far kept schtum about his Pulitzer.

Lamar’s win smacks not so much of tokenism, as of desperation – of the cloistered high-culture set’s desire to remain relevant. But whether or not this kind of creeping high-low relativism is good or bad for so-called high culture, I’m not best placed to say: I’m about as unschooled in cantatas and string quartets as the Pulitzer board seem to be in rap.

But the excitement at the announcement – the ‘finally!’ tweets from people who probably didn’t realise up to now that the Pulitzers did music awards – seems to me bad for pop culture. Suggesting that excellence in rap or rock or pop should be recognised on the same pegging as classical music risks ignoring pop’s mass-culture essence, the very thing that makes it different.

This is not to say that awards like this should only go to struggling unknowns, or that classical music can never be popular. It is that pop music’s mass appeal, its ‘populism’ as Robert Christgau once put it, isn’t just incidental. The collective experience that huge albums, singles and era-defining shows generate are as much a part of pop’s vitality as the intricacies and the craft of the music itself.

What’s more, when it comes to rap and contemporary black music, the obsession with awards, even the more mainstream variety, has been particularly strange of late. Critics are now automatically appalled whenever industry awards like the Grammys, let alone its high-culture cousins, refuse to recognise black pop-culture talent – as if it is the job of the cash-stuffed geriatrics who tend to judge these things to confer legitimacy on black achievement.

Indeed, as any Kendrick Lamar aficionado will tell you, if he was to win any Grammys or Pulitzers, it should have been for To Pimp a Butterfly, his lush, expansive 2015 LP to which the more clipped and rough-edged DAMN., for all its intricacy, fire and hits, didn’t quite match up.

The high culture vs low culture debate feels exhausted. Not least because the high-culture side seems to have pretty much given in. But pop artists should be wary of seeking the approval of elite institutions desperate to give it to them. Part of what makes Kendrick Lamar a strange Pulitzer winner is part of what makes him so special.

Tom Slater is deputy editor at spiked. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Slater_

Picture by: Getty

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.