Germany’s coalition of fear

The new government is built on fear of populism and the public.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

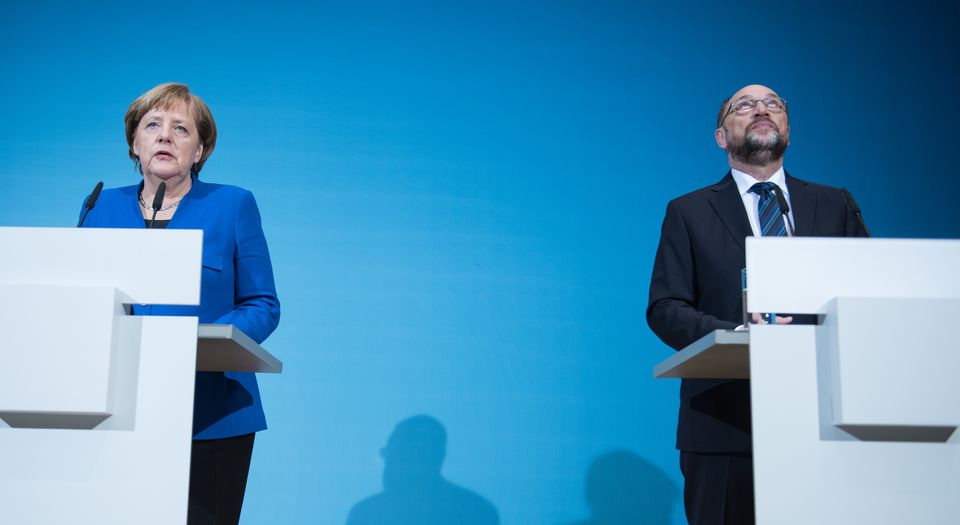

‘People in Germany are waiting for a government… almost six months after the election they have a right to expect something to happen.’ This is what Angela Merkel said as she congratulated the Social Democrats (SPD) for their decision on Sunday to renew the grand coalition. Initially, after the SPD suffered its worst election result ever last September, the party said it would not join a Merkel government; now it has changed its mind and will join forces with Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU).

The ‘new’ government, which actually consists mostly of old faces, didn’t only take longer to set itself up than any other in recent memory; it also comes with the lowest approval ratings of any German government ever. Merkel, now set to start her fourth term in office, seems to be the only person keen to celebrate. ‘Now everyone is back to where no one wanted to be’, wrote Jochen Arntz in the Berliner Zeitung, as polls showed that 52 per cent of Germans reject a new CDU-SPD coalition. The Süddeutsche says, ‘Chancellor Merkel will have to do a lot if she wants to create the sensation of a new beginning’.

But the idea that this coalition could do anything to create a sense of a new beginning is ridiculous. Indeed, the main reason it was formed, in the face of clear unpopularity, was to fend off any serious demands for change. It is a coalition for the status quo – and that means Angela Merkel. Back in September, as her party’s terrible election results were coming in, Merkel was already making no secret of her desire to continue as before. ‘I cannot see what we should do differently’, she famously said.

It was only the SPD’s initial announcement that it would not join a coalition with the CDU – rashly made by a disappointed, unprofessional Martin Schulz, the SPD leader – that led to Merkel trying to form a coalition with the Greens and the Liberal Party. That failed in November. Then Merkel refused to set up any kind of minority government, which would have put more pressure on parliament, or to agree to new elections. She effectively waited for the SPD to come round.

But while it might not be surprising that Merkel, who has never been particularly inspiring, should praise her own work, what is remarkable is the desire across the board to maintain the status quo. Thus, even Arntz, who is no fan of Merkel, said: ‘The SPD did the right thing, because… there was no alternative.’ At a time when change is associated with populism, and with the unpredictable will of the people, it is increasingly feared by many in the political class. In such a situation, even a tired and boring old government is seen as preferable to something else, something new, something the majority might prefer.

New elections, as most pundits tirelessly reminded us in recent weeks, would only benefit the populist Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD), and therefore they had to be avoided at all costs. This was the politics of fear – fear of voters. And it was this fear that led the 464,000 rank-and-file members of the SPD to vote, by 66 per cent, for a renewed coalition with Merkel, even though many of them have a deep dislike for her. ‘The SPD refrained from committing suicide out of fear of death’, was the apt comment in the FAZ newspaper the day after the SPD vote.

The irony of this situation is not just that Merkel has once again come to be seen as the only option, with no alternative, despite her own dearth of vision and ideas. It is also that the AfD leader Alexander Gauland’s famous threat after the September election – ‘We will change the country… we will chase them down, Angela Merkel and whoever else’ – is being vindicated. It is being vindicated by this fearful, voter-avoiding consensus being forged around ‘Mummy Merkel’ and the hope that she will protect Germany from populist passions.

The AfD is certainly not, as Gauland likes to pretend, a force for positive change. Quite the opposite: it is a party which stands for backward ideas, with its opposition to abortion, obsession with immigration, and discomfort with press freedom. Rather, the AfD feeds off of public disillusionment with the main parties. The renewal of the grand coalition proves that if you want change, you have to go against the old establishment; you have to look to the small parties. And, sadly, the party that is seen as most anti-establishment right now is the AfD. This will become more the case now that the old establishment has done everything it can to freeze out the AfD in parliament.

For all the middle-class commentariat’s criticisms of Merkel, they actually share her and her coalition’s fear of the electorate. Consider how both they and the tired members of Merkel’s grand coalition see the EU as far preferable to populists and ordinary Germans. ‘With so many construction sites in Europe, we need a stable government to bring the EU forward’, said a leading commentator at FAZ after the SPD’s decision to join the coalition. When it comes to the question of what is more important – public opinion or the EU view – these people have made their loyalties clear. For now, the AfD increasingly looks like the only opposition. But as the dividing lines between the old elite and the public become clearer, we should hope that something new and genuinely democratic might soon develop.

Sabine Beppler-Spahl is head of the board of the liberal thinktank Freiblickinstitut e.V., which has published the Freedom Manifesto. She is also the organiser of the Berlin Salon.

Picture by: Getty Images.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.