The new puritans waging war on art

Manchester Art Gallery’s removal of a Victorian painting should horrify us.

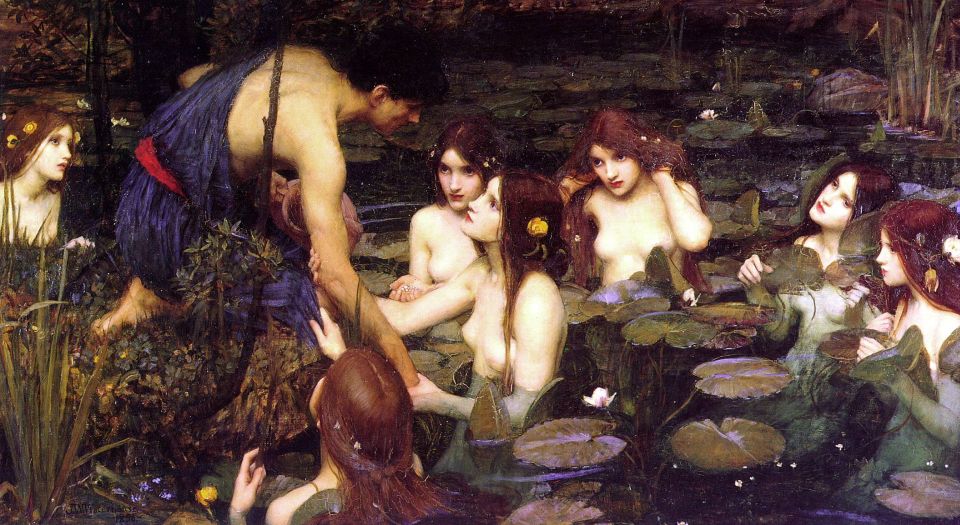

Manchester Art Gallery (MAG), with its renowned Victorian art collection, turned traitor to the cause of art last week. It removed from display a popular Pre-Raphaelite work – John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs – because it shows naked girls seducing a naked boy. In the current climate of #MeToo hysteria, it seems that having such a painting on public view is tantamount to endorsing abuse.

The public expressed their outrage at this act of censorship in no uncertain terms, as evidenced by comments made on the MAG blog and in the gallery itself. And so MAG, to save face, quickly reversed its decision and put the painting back on display. As AC Grayling explains in the Daily Mail, this kind of puritanism can only damage the arts.

But this incident isn’t simply a matter of bad judgement on the part of MAG’s curators. After all, this was not an isolated example of censorship in the arts. Feminist and anti-racist campaigners are increasingly targeting the arts to further their causes, and arts institutions are capitulating to their demands – or, even worse, pre-empting them by engaging in self-censorship.

In December, for instance, the Royal Court theatre, a London venue famed for its commitment to freedom of expression, tried to cancel its production of Andrea Dunbar’s Rita, Sue and Bob Too on the grounds that it might offend victims of abuse. As with MAG, public outrage forced the Royal Court to reverse its decision.

In the US, several galleries have been targeted. In New York, two sisters started a petition demanding the Metropolitan Museum of Art remove a painting by Balthus which featured his neighbour’s daughter in an erotic pose. Elsewhere, an artist called Hannah Black sought to get a painting taken down because its white artist depicted the gory consequences of violent racism against a black boy, Emmet Till. Her letter to the Whitney Art Gallery was signed by nearly 50 people working in the arts. Across the Canadian border, in Toronto, a gallery cancelled an exhibition when the artist was accused of cultural appropriation. These are just a few of the many recent examples of censorship and self-censorship in the arts.

What these incidents suggest is that some leading figures have lost their artistic compass. When MAG said it just wanted to ‘start a conversation’ about the issues raised by Hylas and the Nymphs, it expressed an idea that is eating away at the arts: that art is valuable politically, not artistically.

Clare Gannaway, MAG’s curator of contemporary art, explained that she wanted to challenge how we perceive beauty. For her, the title of the room in which the painting is displayed, ‘In Pursuit of Beauty’, is problematic because the paintings are by male artists presenting the female body as a passive decorative artform. ‘For me, personally, there is a sense of embarrassment that we haven’t dealt with it sooner.’

Although most people were horrified by MAG’s decision to remove the painting, it did win some support. What would have been unthinkable only a few years ago is now seen as a justifiable way of opening up debate, making us rethink what galleries should display. It is no bad thing to reevaluate works of art. Tastes and ideas change. But the debate being opened up by arts institutions wanting to ‘discuss the issues’ is profoundly hostile to art. That’s because the issues involved are not artistic – they are socio-political.

Before MAG reversed its decision, Gannaway reassured us that the painting ‘probably will return… but hopefully contextualised quite differently. It is not just about that one painting, it is the whole context of the gallery.’ In all likelihood, this ‘contextualisation’ will go ahead. In other words, the gallery will be curated in such a way that viewers are steered to think about the issues, not the artwork. Victorian art will be ‘contextualised’ less in terms of an understanding of its techniques, the period in which it was created and comparable artistic works, and more by the politicised preoccupations of our narcissistic moment.

We will be told that we should observe how women are objectified by men and that we should despise Victorian painters for their sins against the present. At least censorship is more honest. It doesn’t try to protect us from art through ‘contextualisation’. This shows contempt not just for art but for the public. Curators don’t trust us to look at art with the ‘correct’ set of preconceptions.

The belief that art needs to be contextualised in this way is not only deeply patronising — it is also opening up a gap between the art world and the public. Mounting their moral high horses, curators and critics see the role of the arts as one of correcting the way people think about the world – to make people see the world as it is seen by these elites: riven by gender bias, racism, homophobia, Islamophobia, corporate corruption, environmental irresponsibility, and so forth. The implication is that if the arts don’t challenge ‘bad ideas’ and ‘bad attitudes’, then they are failing in their responsibilities to society.

But art has no responsibility towards society. An artist’s only duty is to strive to make the best art he or she can. And a curator’s primary responsibility is to look after the art in his or her care. Sections of the art world seem to be forgetting this important task. Instead, artists want to produce social critique and contemporary curators want to shape our responses to art.

MAG presented the removal of the painting as an act of conceptual art – part of a commission by artist Sonya Boyce, which has the purpose of ‘problematising’ MAG’s collection of Victorian art. The gallery says it is thrilled its action has generated such heated debate. But if the comments on MAG’s blog are any indication, many are now casting doubt on the capacity of the gallery to care for Manchester’s public art collection. Curators and artists who think they can police public attitudes should beware: they risk alienating a public who clearly care more about art than they do.

Wendy Earle is convenor of the Academy of Ideas Arts and Society Forum.

Picture: Hylas and the Nymphs (1896), by John William Waterhouse.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.