British women, enjoy your equality

As an Indian I can assure you: harassment is not rife in the UK.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

For months now, the MeToo phenomenon has dominated media discussion. Female empowerment has become the rallying cry of celebrities and columnists, at award ceremonies, in newspapers, on social media. Everyone is talking about sexual harassment and sexual misconduct, far beyond Hollywood, where the MeToo movement started with accusations against Harvey Weinstein. It is now reported that MPs in the UK want an inquiry into women’s experiences of ‘unwanted sexual attention’.

As I was growing up in India, sexual harassment always felt very real and pervasive to me. Cat-calls, brushing up, grabbing, lewd remarks, lecherous staring (which could last a whole 30-minute bus ride) – this behaviour was the norm, a central feature of life in the public sphere for women. It would often feel revolting and stifling; it made you angry and frustrated. Yet now, having lived in the UK for several years, I find myself equally frustrated by the current narrative around sexual harassment, and by the impulse to scrutinise and police interactions between the sexes. This feels wrong, too.

Yes, there have been some allegations of assault or serious harassment as part of MeToo, but much of the focus has been on problematic male attitudes and conduct. The existence of banter, an occasional hand on a knee, a pat on the back, a joke, flirtations in the workplace or at the pub, comments made in the street – these are all presented as evidence that sexual harassment is the norm, and women are victims of entrenched attitudes.

This is a myth. Women in the West are simply not at threat from male behaviour. They do not live under a patriarchy or with constant harassment. For some perspective, let’s look at what an unequal society with traditional norms and limits actually looks like. In India, I had the privilege of a liberal upbringing: my family treated my brother and I no differently, and I had the freedom to choose, argue and think for myself. And yet there were limits on my life, imposed by societal norms and realities. Limits to where I could go, whether I could be unescorted, what I might wear, how late we could stay out. Commuting involved developing strategies – you might carry a needle to ward off stray hands in crowds; wear a rucksack over the chest at all times; have your elbows primed; watch men like a hawk and avoid any ‘accidental’ contacts with them.

This is a far cry from daily life in the UK. And for feminists to insist otherwise is bizarre. Much of what has been flagged up as part of MeToo has involved men making actual advances, not harassing women randomly and constantly in public spaces. To me, having experienced life in an unequal society like India, this looks less like harassment than sexual interaction between equals. It is an assumption of sexual freedom that men, and women, too, take it for granted that British society allows the space for ‘unwanted’ advances, otherwise known as flirting.

In a society where unequal attitudes are the norm, it is impossible to have these interactions. Women in traditional cultures are often treated as objects of reverence: the woman as goddess and therefore a symbol of virtue and muted strength, to be patronisingly respected and protected. This is no better than being treated constantly as a sexual object. Either way, your agency as a free individual is denied; you are a woman first, a person second.

When I first moved to the UK as a university student, it felt truly empowering to be in the public space and to walk with confidence and freedom. I could negotiate and tackle public life with ease, engaging with people not as a woman, but as an individual with a mind, a mood, a personality. It felt genuinely liberating to be able to walk down a street without feeling stifled by a prescriptive set of rules on how to behave or where to go.

There are no overarching social norms and mores limiting women’s liberty in the UK. What’s more, men here just get on with day-to-day life without being overly aware of the presence of women around them. Women do not leave their homes every morning thinking, ‘Can I wear that without drawing undue attention to myself?’. We do not carry umbrellas or wear heels just so they might be used as weapons against men on railway platforms.

One of the reasons there is such an unhealthy dynamic between the sexes in India is because there is an unhealthy attitude towards sexuality in general: repressed sexuality prevents free, honest interactions. The MeToo campaigns gaining ground in the UK seem to want to reverse the progress on women’s empowerment in order likewise to repress certain aspects of sexuality; to make women ‘off limits’ to any kind of attention, and to treat them effectively as objects of reverence, requiring protection and a special respect.

We must resist this false narrative that says sexual harassment is pervasive in British society, and the wilful conflation of serious incidents with everyday interactions. There is something perverse and dangerous in writing such a narrative, with no regard to facts, truth, or the importance of allowing free women and men to negotiate public life as they see fit. To me, it is particularly sad that instead of encouraging women to celebrate the freedoms we can take for granted in Western societies, and to enjoy the fact that we can express ourselves as individuals, campaigners want to make us feel fearful and atomised.

Sadhvi Sharma is a writer and researcher based in London, and has a PhD in international political economy from the Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore.

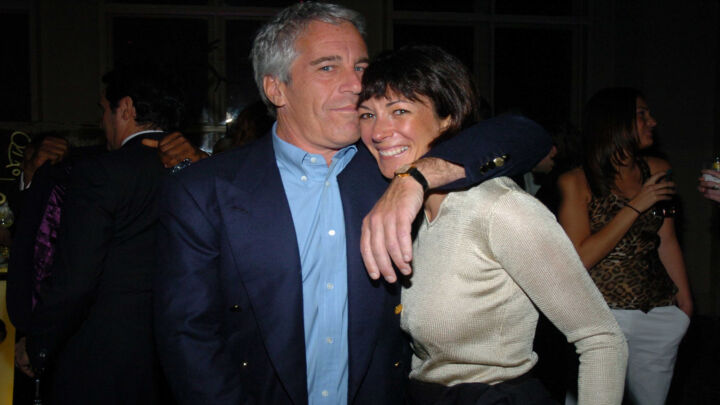

Picture by: Getty Images.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.