Basquiat versus Banksy

One was an artist, the other just a talented graphic designer.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

On the eve of the opening of a new exhibition of art by Jean-Michel Basquiat in London, Banksy revealed two painted homages to his American predecessor. The contrast between the most famous exponents of two different generations of street art from opposite sides of the Atlantic could not be greater.

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) is widely considered the founder of the street art movement, which is the crossover of, on one side, graffiti art, mural painting and inscribed poetry and, on the other, the fine arts of museums and galleries. In theory, street art could be simply graffiti or posters from non-gallery settings relocated into museums and galleries, but in practice this is rarely the case. More often, creators who began by making graffiti start working on more portable supports (like the traditional artist’s canvas or board) when there is a commercial imperative. They also make prints or multiples with professional assistants.

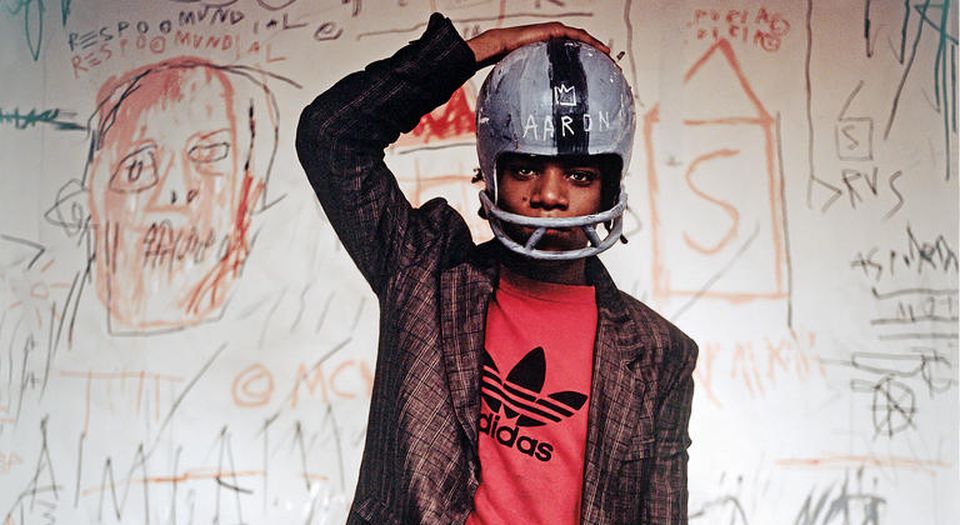

‘Basquiat: Boom for Real’ (Barbican Art Gallery, London; closes 28 January) collects a wide range of Basquiat’s art made over the whole of his short career. Visitors can judge for themselves Basquiat’s stellar status in the art world. (This year a painting by him sold at auction for $110million.) The art was made in a mixture of fine-art materials and ordinary materials from drugstores and discount stores. Paint, oil sticks, spraypaint, pencil and marker were used on canvas and board but also on more unusual supports such as foam rubber, doors, plates, a refrigerator and even a football helmet. Subjects include street life, modern life, racism, sports, music, popular culture, ancient history, the Western canon, anatomy and mortality. All manner of seemingly random fragments of history surface in Basquiat’s paintings. Simple icons, lists of words, graphic symbols, colourful abstract painting and meandering grids occupy a variety of surfaces.

A weak point of Basquiat’s art is that sometimes his ideas do not seem decipherable to viewers, and perhaps were not even clear to the artist himself. Following the trail of a person’s subconscious can be frustrating without sufficient clues and background.

Although Basquiat was not the creator of the first street art (consider the New York and Paris photographers who documented graffiti in the 1930s and Jean Dubuffet’s crude faux-naïf figures of the 1940s), he is the breakthrough figure. In 1978 graffiti began appearing around downtown Manhattan, featuring a character (or author) called SAMO©. SAMO© SAVES IDIOTS. SAMO© AS AN ESCAPE CLAUSE. SAMO© ||| 4 THE SO-CALLED AVANT GARDE. Other cryptic phrases seemed a cross between political slogans and poetic riddles. SAMO© was an alter ego that Basquiat created. The phrases caught people’s attention and provided Basquait with an entrée into the artworld, which was in search of novelty and danger. Basquiat soon discarded his SAMO© persona and embarked on a series of dramatic paintings and sprawling drawings, which were displayed in New York exhibitions and quickly sold.

More than a few people have noted that the idea of the primitive black creator is periodically used to reinvigorate Western art; be that Gauguin going to Tahiti, Picasso being inspired by African masks, or the Surrealists adopting Oceanic masks. Did smart New York gallerists pick Basquiat to be their dangerous primitive? Basquiat was far from a primitive – he was the child of middle-class Haitian-Puerto Rican parents. He was not the untutored child of poverty, ignorant of art. He visited museums as a child and youth, drew obsessively from a young age and was very familiar with art history, from the Ancients up to pop art. All of this came out in his art. He delighted in blending street references, pop culture and high culture, leaving viewers impressed but baffled. He liked existing in multiple worlds simultaneously.

There is a debate among fans and scholars of the Beat Generation about what constitutes beat art. The 1950s writings of Beat Generation authors Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs and Gregory Corso are distinctive and celebrated, but beat art (if it exists) is a lot harder to pin down. It may be that the only real beat art is by Basquiat. Basquiat met Burroughs and paid homage to his cut-up method. Basquiat read and admired Kerouac and listened to jazz – the favoured music of the beats – while he painted. His paintings are full of repeated phrases, snatches of slang and jumbling of pop culture – a heap of material he trawled in the hope of coming up with an unexpected truth or line of poetry. Basquiat’s patterns often resemble musical scores, lyrics and repeated cellular structures that evoke musical notation. A search for hidden truth and rejection of the standard interpretation were at the core of beat philosophy.

Once he emerged as a star of the New York scene in 1981/82, Basquiat achieved great prominence and wealth. He was an artist, writer, actor, musician and dj. He collaborated with Andy Warhol and Keith Haring. He performed in the music scene of New York and dated Madonna. With the music, money, hectic socialising and acclaim came drugs, mainly heroin, which would claim his life in 1988. The parallels between Basquiat and the dead of the 27 Club (musicians who died aged 27, including Hendrix, Joplin, Morrison, Cobain and Winehouse) has been noted before. Basquiat’s sudden rise, fame and fortune, drug use and sudden death aged 27 are common to all of those musicians.

Part of the cachet of street art is the aura of authenticity, or rather its perceived authenticity: the truth doesn’t matter much. The legend of Van Gogh has him painting wild with passion in a frenzy of unhinged creativity. In actuality, Van Gogh did have manic episodes but he painted carefully and methodically. But many like the idea of art coming from untrammelled passion. As creators of street art, Basquiat and Banksy have credibility rather than authenticity: Basquiat did not make drawings on walls and Banksy works with assistants. No matter. Thankfully, we care more about art than the status of the creators.

So, how good is Basquiat? On the evidence here, at his best he was very good, but his art is often below that standard. Whether it was the effect of drugs or the numbing effect of producing work in great quantity for a relentless round of international exhibitions, Basquiat did repeat himself. In the best art – the painterly early works and the self-portraits (half-humorous, half-sinister silhouette ciphers) – his art fizzes with energy. The art feels raw and exciting, sometimes frustratingly arcane and sometimes daft, but always vibrant. Which brings us to Banksy…

British street artist Banksy has made a name for himself creating pithy interventions, often containing social commentary or promoting progressive political themes. The works need planning, including the creation of elaborate stencils that are used with spray paint on site. The messages sometimes sacrifice logic and depth for clarity and humour. Visually, some of the designs are inventive and they do reflect subjects of modern life. But as art they lack a lot.

Basquiat’s art is alive because we see the artist changing his mind, discovering, adapting and revising. We see the art as it is being made. While Basquiat’s art is palpably alive, Banksy’s is dead – it is simply the transcription of a witty pre-designed image in a novel placement. There is no ambiguity or doubt, no possibility of misinterpretation. There’s no fire and no excitement. Banksy is not much of a thinker and his political positions are often lazy and safe. He confirms the biases of his fans and never genuinely provokes a confrontation with painful truths. In short, Banksy takes no risks. Ultimately, Banksy is just a talented graphic designer with a sense of humour – he is not an artist.

That is why, a century from now, people will still be looking at Basquiat but they will have forgotten Banksy.

Alexander Adams is an artist and writer. His latest book, Letter About Spain, is published by Aloes.

Basquiat: Boom for Real is at the Barbican Centre, London, until 28 January 2018.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.