The cultural revolution on Western campuses

The alarming parallels between today’s student censors and Mao’s Red Guards.

It is a very popular ploy these days to dub your political opponents ‘fascists’, or to suggest their views herald a return to the dark days of the 1930s. This kind of hyperbole is as galling as it is tedious.

But after living in China for six years, and observing from a distance the illiberal tendencies present on many university campuses in the West, some historical parallels do illuminate the contemporary situation. That is to say, it is not mere rhetorical bluster to suggest that the student-led witch-hunts against academics who criticise their politics, the student-dictated curriculum changes, the prevalence of trigger warnings and so on, carry an echo of events in 20th-century China.

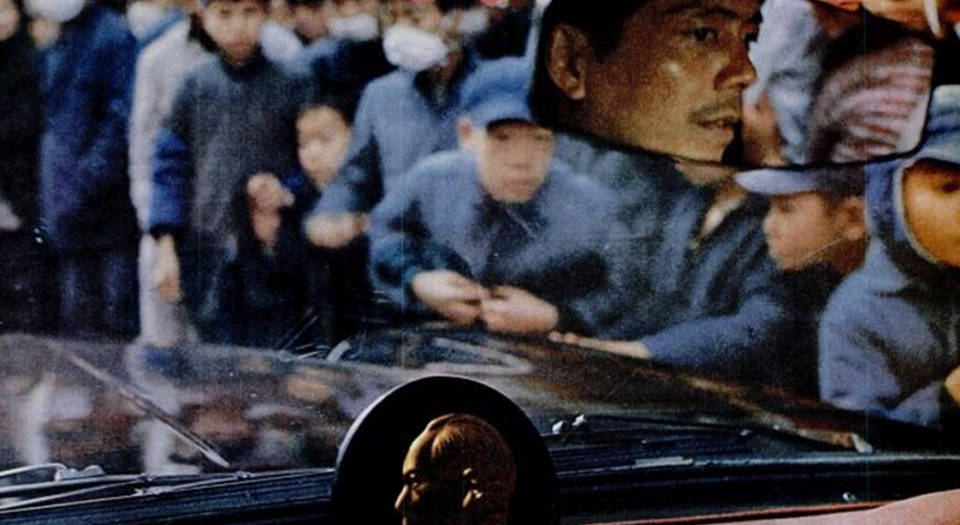

The Cultural Revolution

Fifty years ago, as Mao Zedong’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution took hold, TIME magazine ran with the headline, ‘China in Chaos’. In his memoirs, written exactly 25 years ago, Ji Xianlin describes a ‘dizzying descent into hell’. Ji, a leading Beijing academic, suffered injustice, humiliation and brutality. He published his memoirs so that lessons could be learned. Entitled The Cowshed, the memoirs are a testament to a world turned upside down. It should be a must-read for everyone in academia, for it is a tragic lessons-from-history primer. It is guaranteed to send a shiver down the spine.

Students were at the forefront of Mao’s Cultural Revolution. They were officially empowered to denounce tutors who refused to follow official speech codes; to punish any criticism of the regime; to undermine teachers who refused to fall into line; and to shame dissenters. These students were intolerant of established authority and elitist intellectual ideas. It was an anarchic era based on ‘thought-reform’, enforced by public humiliation, mental and physical intimidation, and self-criticism aimed at ensuring conformity.

Fifty years on, it’s worth assessing this moment of collective madness and comparing it to the strange inversion of educational authority occurring in Western, predominantly American, universities today.

Of course, the differences between 1960s Communist China and 21st-century Western academia are as profound as the similarities. But, in the spirit of Ji, maybe it is worth emphasising the dangers so that we might learn something. China, after all, was attempting to mobilise a new generation to be involved in politics and the Cultural Revolution was intended to purge society of its politically backward and dated ideas. The Cultural Revolution’s ambassadors thought they were acting with the best possible motives.

The Cultural Revolution began on 8 August 1966, and lasted for 10 brutal years. During that time, hundreds of thousands of people lost their jobs, their homes, their dignity, their minds, their lives. The Chinese Communist Party waged this nihilistic crusade in order to ensure that older generations and established ideas did not undermine the creation of its new vision of society. This would be a new society purged of ‘the four olds’: old customs, old habits, old culture and old ideas. They would, of course, be replaced by new progressive versions. It resulted in a decade of destruction, one in which students took up cudgels against their teachers, professors, intellectuals and other ‘problematic classes’ in order to produce their version of the good society. The devastation wrought is only now being admitted and acknowledged in polite Chinese society.

In 1966, the Chinese authorities announced that people had to ‘criticise and repudiate the reactionary bourgeois academic “authorities”… and to transform education, literature and art’ (1). The old ways of doing things were seen as corrupt, old-fashioned, reactionary and reinforcing an outmoded worldview. To create a platform for new ideas to flourish, ‘bad elements’ had to be expunged.

Statues were destroyed, historic images demolished, books burned, teachers sacked, scholars punished, intellectuals bullied. The campaign was designed to wipe out ideas and thoughts fostered by the old, educated classes – concepts deemed irrelevant to the political needs of the young. Ji writes of students lecturing their professors in correct behaviour. Schools and university curricula were dismantled. In the era before social media, being named as a dissenter in a big-character poster – huge banners that named and shamed targets – was enough to end someone’s career or worse.

Fast forward 40 years, and there is growing evidence of a corrosive tyranny of student illiberalism. Greg Lukianoff, president of the US-focused Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, speaks of a ‘cowed conformism’ in higher education. Twitter and YouTube are the new big-character posters. Professors’ heads are once again bowed.

The new puritans

We see Washington State’s Evergreen State College president George Bridges cowed and capitulating to student demands, including addressing them using gender-neutral pronouns; we see Evergreen professor Bret Weinstein condemned, intimidated and threatened for dissenting from the student-activist call to ban white people from campus for a day; and we see Yale faculty member Nicholas Christakis and his wife having to endure a verbal haranguing by students and then being forced to resign, all because they questioned the no-offence culture on campus.

In another strange parallel to the Cultural Revolution, Ji, who was brutalised and beaten for many years, continued to pay his Communist Party dues throughout. He believed that it was merely miscreant elements who were responsible for his troubles and it would be the party, the system, that would ultimately save him. For Ji, it was some kind of terrible mistake. Likewise Professor Weinstein at Evergreen College points the finger at Bridges, the college president, but remains loyal to the college itself. For both, the nightmare in which they find themselves is an aberration. Both prefer not to confront the fact that the authorities are the ones licensing student intolerance (albeit under the guise of eradicating offence and hurt). Like Ji, they don’t see that the perpetrators, the militants, the guardians of the new codes are merely following official logic.

In 1960s China, the Red Guards were the bright young purveyors of left-wing radicalism, determined to remove feudal educational content, and to open up ‘educational opportunities for the underprivileged’ (2). One report records that students exercised a ‘high sense of moral and political purity’. Many saw the Cultural Revolution as an experiment in a new form of democracy, and in this experiment, brutality was a necessary means to denounce inequality. By 1967, radicals had begun what they called the ‘seizure of power from below’ (3). Final-year curricula were re-engineered by first-year students to eliminate the elitism. Course length was reduced to two years, examinations were suspended.

A new puritanism had emerged. Anyone found acting in a culturally unacceptable manner would be intimidated and beaten. Censorship was everywhere employed for the purposes of imposing correct viewpoints on society.

One ex-member of the Red Guard called Mo Bo recalled the excitement generated by the turnaround in power relations. She writes: ‘In the past our teachers had been intimidating. Now the situation was reversed: whenever teachers came across a student they would lower their heads.’ (4) By the end, things had escalated to nightmare proportions. One student relates how, in a Beijing middle school, students beat one teacher to death. ‘It was immensely satisfying’, he writes (5).

Paraded in public, forced through ‘struggle sessions’ to admit unwarranted guilt, beaten up for asserting the wrong cultural and intellectual sentiment. And the authorities encouraged and endorsed this intolerance. As Mao himself put it, ‘the direction of your battles has always been correct… you have done the right thing and you have done marvellously’ (6). Likewise, Evergreen’s Bridges writes of the students who literally blockaded his office: ‘We are grateful to the courageous students who have voiced their concerns… We want to come together with you to learn from your experience.’

In an echo of the ‘four olds’ campaign, today’s students have demanded the removal of portraits of the founder of Yale’s Calhoun College, John Calhoun, a ‘notorious slavery advocate’, and succeeded in convincing the authorities to consider renaming the college. Student activists of the Black Justice League at Princeton University claim that Woodrow Wilson’s ‘racist legacy’ means that using his name for an undergraduate college and school is a ‘spit in the face’ of black students, and that it should therefore be erased. At the University of Oxford, students waged a campaign to destroy a statue of Cecil Rhodes, on the grounds that this monument to an embodiment of racism and imperialism was ‘ahistorical and inappropriate’.

Little wonder that Nadine Strossen, author, law professor and former president of the American Civil Liberties Union, warns that ‘free speech is being limited by making speech unsafe to listen to’. Established intellectuals have been refused speaking rights in many British universities for so-called ‘offensive’ comments; certain newspapers have been banned in London’s leading journalism school; #RhodesMustFall activists burned books and tore down paintings in South Africa; and student puritans in the University of Birmingham have demanded segregated living quarters.

Of course, no one in Western academia has paid for his or her dissent with his or her life. And few, as yet, have been sacked. The correspondences between now and the Cultural Revolution aren’t straightforward. However, there is clearly a strange shift in power relations between staff and students in the Western academy today that echoes the same shift in 1960s China. And it is creating professional trepidation in higher education. Teachers now simply accede to student demands to avoid humiliation. It is a growing and worrying trend to see speakers – however disagreeable – shouted down and prevented from speaking, whether at Middlebury College or Princeton University.

Earlier this year, Baroness Wolf, a professor at King’s College London, warned that ‘universities are increasingly nervous about doing anything that will create overt dissatisfaction among students’. The collapse of authority allied to the privileging of the ‘student voice’ creates a situation whereby the university, as one Evergreen lecturer puts it, ‘uses fear tactics to rally the masses and prevent students from thinking clearly’. In this context, it is heartening to read the recent open letter by 17 Evergreen students, part of which reads:

‘We reject the McCarthy-esque witch-hunting which has taken place. Simply crying racist has become sufficient to destroy credibility and empower accusers. This has been accompanied by vigilante action against those dubiously accused racism, and this behaviour has not been reined in by the administration.’

Within two years, even Mao had realised that things had gone too far and reined in the toxic excesses of the Red Guards.

In 1981, the Chinese Communist Party led an assessment of the years since the foundation of the People’s Republic of China. It condemned the Cultural Revolution and admitted that ‘confusing of right and wrong inevitably led to confusing the people with the enemy’. It’s a lesson from history that some of today’s campus activists could do with learning.

Austin Williams is associate professor of architecture, XJTLU University, Suzhou, PR China, and director of the Future Cities Project

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.