Long-read

The poet who vanished

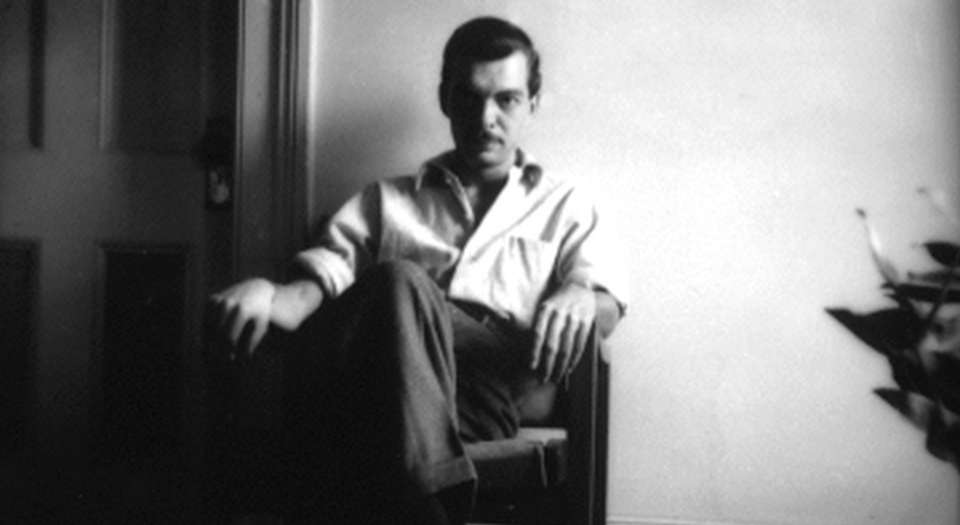

The prodigiously talented Weldon Kees might have had it all. Then, in 1955, he disappeared.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Anyone who picked up a new copy of the New Republic from his or her local newsstand on the morning of 18 July 1955 could have opened it to read an article called ‘How to be happy: installment 1053′. What they couldn’t have guessed is that the author would, in all probability, choose to extinguish his life mere hours later. With a flourish sour, sardonic and elegant, the author would disappear. His name was Weldon Kees.

Kees had the knack of being in the right place at the wrong time. As a writer-artist, Kees had been in all the best cultural hotspots of the period. He was in New York in 1943-48 during the early Abstract Expressionist boom, but left before the market took off. He had also been in artists’ haven Provincetown, but had sold relatively little work. In 1950, he arrived in San Francisco. Somehow he had managed to be in these places and failed to make critical breakthroughs. He (and his wife Ann) had quit places without getting the most out of them. He seemed to have turned missing opportunities into his greatest art form.

Admired for his talents as a poet, storywriter, critic, musician, composer, painter, film-maker and photographer, Kees never broke through in any one field despite his talent. The only thing he had made a sustained success of was reviewing. At parties, the elegantly-dressed figure with matinee-idol looks, cigarette in hand, would cast an acerbic gaze over the assembly. Kees was a good jazz pianist and often played in small bands. His self-deprecating wit and musical skill (not to mention his looks) made him a hit at social gatherings. He did not lack ambition, application or ability and had talent in abundance – perhaps too much talent in too many fields.

Looking at the drinkers around him, Kees sharpened his stiletto-sharp wit for the next conversation or letter. Kees was one of the great letter writers of his time. In long, observant and funny dispatches, Kees documented his misfortunes and the doings of others. Only a limited selection of these letters has been published. A more extensive collection of letters would make an intimate and entertaining insight into American arts of the 1940s and 1950s.

Born in 1914, Kees grew up in Beatrice, Nebraska, a small midwestern town. Kees studied English at nearby Lincoln, at the University of Nebraska, where he met fellow student Ann Swan. They would marry in 1937. Already a published writer of short stories, Kees worked as a librarian in Denver before the couple headed to New York. He painted abstract pictures, made collages and published where he could, while all the time earning a living in the film industry. (Kees edited newsreels for Paramount.) He worked on a novel that no one ever found quite satisfactory.

Of all Kees’s output, it is his poems that attract most attention today. Kees’s poems were published in the best magazines and reviews, but his three slender books of verse sold poorly despite positive reviews. His poetry is laconic, mordant and very approachable. In an early two-verse poem he recollected a friend’s funeral.

I remember the clumsy surgery: the face

Scarred out of recognition, ruined and not his own.

Wax hands fattened among pink silk and pinker roses.

The minister was in fine form that afternoon.

I remember the ferns, the organ faintly out of tune,

The gray light, the two extended prayers,

Rain falling on stained glass; the pallbearers,

Selected by the family, and none of them his friends.

Oddness of tone and morbid subject matter have prevented Kees’s verse appealing widely but through waves of minor revivals it has developed a cult following. In Kees’s sardonic satires of small-town life, an outbreak of premeditated bloodletting or Gothic horror is an ever-present threat. This was no literary stance: Kees believed that culture and civility were a thin veneer.

A sequence of four poems about a character called Robinson is Kees’s best (and best known) poetry. Robinson is a cipher of modern man: an urbane yet hollow man, damned to an obscurity so intense that even a mirror cannot reflect his image. Robinson has the attributes of – but not the presence of – a man.

The dog stops barking after Robinson has gone.

His act is over. The world is a gray world,

Not without violence, and he kicks under the grand piano,

The nightmare chase well under way.

The mirror from Mexico, stuck to the wall,

Reflects nothing at all. The glass is black.

Robinson alone provides the image Robinsonian.

A mass of small disappointments had accumulated and, as he turned 40, Kees seemed increasingly depressed and preoccupied. The failure to write a successful stage play or novel limited his ability to appeal to a wide audience. Added to this, he had personal problems. In July 1954 his marriage broke down. Ann’s drinking became uncontrollable and she had a mental breakdown. Despite Kees’s efforts to help her, they separated. The last year of his life Kees would spend alone except for his cat Lonesome.

On 19 July 1955, the police found Kees’s Plymouth parked by the Golden Gate Bridge, keys in the ignition. The police found no suicide note nor did the searchers of Kees’s apartment. His cat was there and nothing seemed amiss. He had had plans for the coming weeks and had not appeared outright suicidal. Friends did, however, say Kees had, of late, been more withdrawn and anxious than usual. He had talked of heading to Mexico.

Friends said Kees’ apparent suicide seemed to be another mistimed move. In 1955, Kees appeared on the verge of wider acceptance and success. For readers today, Kees is one of the most distinctive and original writers of the period, and one who continues to provoke curiosity and admiration.

In The Poetry of Weldon Kees: Vanishing as Presence, a new study by Professor John T Irwin, Kees’s disappearance is discussed as a consciously artistic act. Irwin considers Kees’s disappearance in the light of his poems and vice versa, and traces influences upon Kees’s thinking by rereading the many authors Kees mentioned in his own writings, paying particular attention to mentions of suicide and resurrection. Kees had even sketched out the plot of a novel about a biographer’s quest to discover a missing poet.

Irwin notes that in a book Kees had prepared for publication shortly before his death, he had included the uncanny case history of a man who suffered temporary amnesia. Two years after his memory loss and disappearance, the man regained his memory and took a cab to his previous home and was discovered sitting in the living room by his wife, who had given him up for dead. It was as if a dead man had resurrected himself in the most unshowy and ordinary manner possible.

Kees had also been working on a book of famous suicides when he died. He had expressed great interest in literary treatment of suicides, and at his bedside were found two books mentioning suicide. He had a fascination with the poet Hart Crane, who had drowned himself by jumping off a ship in 1933. Kees, it seems clear, considered suicide an existential and aesthetic act and had considered it at length. Beyond the deaths explicitly addressed in his poems and stories, there is a recurrent theme of everyday life ruptured by an unexpected violent act.

Irwin’s focus is Kees’s poetry rather than his life. He demonstrates that Kees’s meditations on death are his central preoccupation as a poet. For anyone interested in the verse of Kees The Poetry of Weldon Kees is an elegant, short and informative companion volume to Kees’s Collected Poems.

Although acquaintances would keep an eye open for him whenever they visited Mexico, Kees was never seen after 18 July 1955. No musical recording or poem similar to Kees’s appeared under a pseudonym. The consensus is that he drowned on the night of 18-19 July. Friends remember that Kees talked of suicide and of going to Mexico. Peculiarly, he may have found a way of doing both. By jumping from the Golden Gate Bridge at midnight during ebb tide, his body would have been carried out to sea and possibly taken by currents south to Mexico waters.

But who can tell? Like an accomplished magician, Kees never did reveal the secret of his vanishing.

Alexander Adams is an artist and writer. His latest book, Letter About Spain, is published by Aloes.

The Poetry of Weldon Kees: Vanishing as Presence, by John T Irwin, is published by John Hopkins University Press. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.