Long-read

The intellectual masses

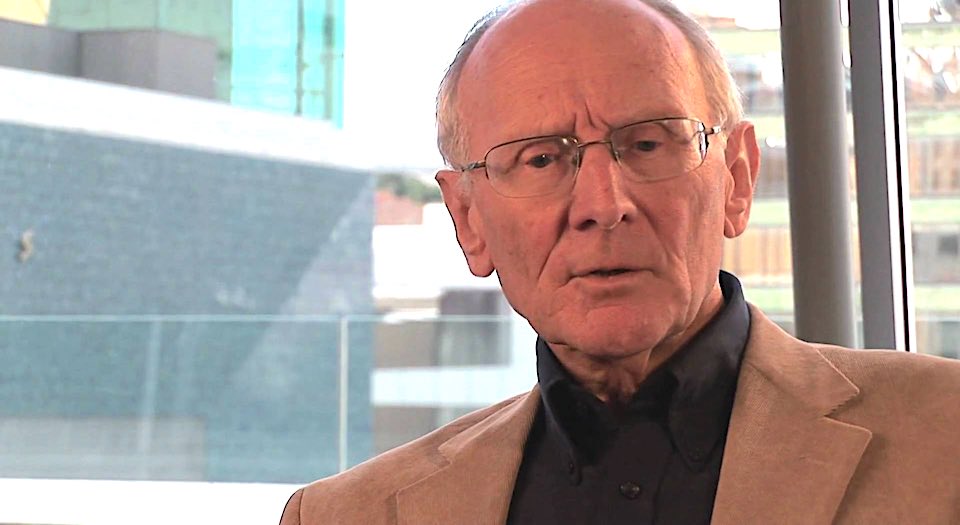

John Carey talks to Tim Black about making Milton palatable, the art of persuasion, and the value of modernism.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

‘I do think Paradise Lost is a tremendous challenge for modern readers, who are not used to reading narrative poetry and probably take against what they understand to be Miltonic morals. So I just wanted to try to make it more palatable, by shortening it, and by introducing it in a way that links it with certain modern understandings.’

John Carey, Merton Professor of English Literature at the University of Oxford until his retirement in 2002, and a familiar public voice thanks to his prolific reviewing and criticism, is talking about his latest venture, The Essential Paradise Lost. ‘It’s a third of the length of the original’, he continues. ‘It’s no longer than Animal Farm. It’s really a novella now.’

Still, as impressive a feat as it is to edit Milton’s masterpiece over 350 years on, it could be seen as a risky move for a scholar and critic who, ever since the publication in 1992 of The Intellectuals and the Masses –his searching, scathing critique of the anti-democratic sentiment underwriting modernism – has been derided for an anti-elitism that, according to his detractors, morphs all too easily into outright anti-intellectualism, an assault on the life of the mind itself. Is he not worried that he’ll be accused of dumbing down? ‘That’s a perfectly possible criticism’, he says. ‘Making a work more palatable can be seen as dumbing down. But I’d say what I’ve preserved is the argument of the poem, and the best passages.’

It’s a typically, disarmingly straight answer. As is the follow-up. ‘I can remember as a teenager being a given a book of literary essays – I have no idea why’, he says, laughing at the memory. ‘And it featured one by Edgar Allen Poe called “The Poetic Principle”. Poe starts out by saying that there’s no such thing as a long poem. All long poems are made up of short poems joined together by bits that aren’t poetry. And in the second paragraph he cites Paradise Lost. I had quite forgotten this, and it came back to me as I was doing this.’

Because that is precisely what Carey has done. He has replaced the longeurs with short narrative summaries, foregrounding those passages that, for Carey, are the reason for Milton’s sublimity – indeed, the reason why people, outside academia, might start reading Milton again. And this touches on Carey’s critical vocation, indeed his academic mission in general: to bring people in – to demonstrate that seemingly difficult literature, too often sequestered in the citadels of high culture, could be something from which everyone and anyone could derive pleasure.

Besides, listening to him, I doubt that Carey, his intellect as formidable as it is generous, is capable of dumbing down Paradise Lost. He’s too in love with the textures of meaning and sound, besotted still, after his first proper encounter as an undergraduate in the 1950s, with the immensity of Milton’s expressive vision. His passion is infectious. The quotes come effortlessly, as he talks excitedly of Milton’s female viewpoint, his rewriting of Eve in a sympathetic, human light, his inventing of scripture as he goes along; and he talks, too, of Satan’s appeal, an expression, he argues, of Milton’s subconscious resentment over his personal and political tragedy during the 1650s, having lost his sight, many of his loved ones, and his struggle for a republic. ‘I think his subconscious resented this mockery of justice. That’s why Satan is so convincing. He has been defeated, but he is undaunted, a “study of revenge, immortal hate. / And courage never to submit or yield”. That, I think, is what Milton felt, mainly through Satan.’

So by abridging Paradise Lost, Carey is not diminishing or dumbing down ‘the best which has been thought and said’, to quote Matthew Arnold (a poet he admires, and a critic he loathes); he’s democratising it. He’s giving the reader the Milton that he loves so that they might love him, too. ‘That’s the whole point of my edition of Paradise Lost, and it’s the whole point of my criticism, too’, he explains. ‘To try to find ways to make something assimilable, likeable, valuable to people who otherwise might not approach it.’

Carey’s vocation, his desire to render great literature accessible, to demonstrate its value (potentially) to all, has its origins, in part, in his own life story, recorded wittily and movingly in The Unexpected Professor (2014). There we first encounter a young Carey as an ‘abnormally self-contained, self-absorbed little boy’, from a modest, middle-class family – his father was an accountant on his uppers, his mother a housewife. No one in the Carey family had been to university before. And his childhood enthusiasms consist of the Beano, Enid Blyton, and occasionally Hotspur and Champion. But grammar school was to raise Carey’s sights. Thanks, he suggests, to both the academic competitiveness engendered in him at Richmond and East Sheen Grammar School for Boys, and the teachers ‘who made you want to be like them – to know the things they knew and value the things they valued’, he drove himself, a lower-middle-class boy from the suburbs, into the heart of learning, of culture and, for too long, of privilege. And in doing so, he encountered resistance, snobbery and the disdain of academics, like that of the economist Sir Roy Harrod who referred to him as a ‘nobody’ to a college guest.

He writes of feeling like an ‘intruder’ while an undergraduate at St John’s in the mid-1950s; of his anger at the unabashed window-smashing snobbery of Christ Church while teaching; of his active undermining of the public-school-favouring admissions policy at Keble while a tutor. And yet, despite his sense of being a class outsider, he was able, ultimately, to gain access to this world, to become Merton Professor, to become a highly respected reviewer, and to sit on assorted book-judging panels, including the first ever Man Booker International Prize in 2005.

In a sense, then, his critical and academic desire to open the doors to literature, to make the canonical accessible, is born of his own experience of and struggle against those who would restrict access, who would treat the cultural sphere as little more than a means to affirm and mark out their distinction from those they deem ought to be beneath them.

Yet Carey is also careful to point out that making great literature accessible, publicly justifying its value, is very different from telling people they must read something, and assuming that one’s own judgement is absolute. And in this, he captures something important: the discursive nature of cultural value, its perpetual emergence through an exchange of views, a mutual act of persuasion, rather than ‘you must like this’ coercion.

‘I have a letter from someone who was at the same school as me, two or three years below me’, says Carey. ‘I was a prefect apparently, and this lad said to me that he was reading HG Wells, and I said “You should go away and read a proper author”. Can you believe it?’, he says, chuckling at his youthful pomposity.

‘So I wrote back to say I blushed at my folly. Of course when I read Wells, I realised what a genius he was. My opinion can be changed. I can be persuaded to read a writer that I have written off, and realise what a fool I was. And if someone came to me, and said Wells was not a very good writer, I would try to persuade them otherwise. And that’s what I’ve tried to do with Paradise Lost, to take certain passages and say, “Don’t you think this is magnificent?”. I would take the Time Machine for Wells, and argue that it shows an astonishing imagination – an attempt to show the likely fate of mankind. Astonishing and convincing.’

Carey is adamant on this point. ‘Persuasion matters’, he says. ‘It’s how changes [in what people might value] happen. Good changes.’

But for Carey, persuasion is very different to issuing commands from some sort central bureau of culture, or an institute for good taste. There is no last word on what is valuable and what is not, no state-sanctioned authority dictating the best which has been thought and said in the world, as there is, effectively, in Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy. He is not interested in forcing people to read Milton, or Wordsworth or Conrad. Rather, it is all about the ‘inward persuasion of the mind’, as John Locke had it, something, Carey says, that Milton anticipates. ‘Satan says an interesting thing in Paradise Lost: “Whoever overcomes by force, hath overcome but half his foe.”‘

Yet at points, Carey’s refusal to impose his judgement on others, and his emphasis on the subjective nature of all judgements, writ large in What Good are the Arts? (2005), a witty unmasking of the pretentious and disdainful, can seem to lead him perilously close to that most bottomless of seas: cultural relativism. Yet, I think this, too, owes less to some sort of ‘anything goes’ relativism – ‘I wouldn’t say any opinion is as valid as any other’, he tells me – than his aversion to the privilege-affirming, status-justifying uses to which the literature and the arts are still too often put. ‘I don’t say you ought to value this poem or book. I say you might – you might well find it valuable. But I never want to say, and I hope I don’t, that if you’re not persuaded, then you’re inferior. And that I think is the real danger. You end up scorning more than half of the human race.’

Which brings us to The Intellectuals and the Masses, a ‘simple cultural study’, as he calls it, which unveiled the repellent class prejudices driving the conception of culture and literature of many of Britain’s most well-known and esteemed 20th-century intellectuals. Their animus, Carey argued, was informed not just by the massive growth in Britain’s population – ‘breeding like rabbits’, as Ford Maddox Ford’s unreliable, aristo-phile narrator put it in The Good Soldier – but also by that population’s political and social empowerment in the form of those twin universals; suffrage and education. ‘The overcrowding, the taking over of privileged positions by the masses – all of that was very hurtful to people who thought of themselves as refined, with refined sensibilities’, Carey explains. ‘But while it is understandable, it is not excusable.’

Those who could excuse it must be thin on the ground, given the obnoxiousness of the sentiments. Here’s WB Yeats on population growth: ‘Sooner or later we must limit the families of the unintelligent classes’. Here’s TS Eliot on education: ‘There is no doubt that in our headlong rush to educate everybody, we are lowering our standards… destroying our ancient edifice to make ready the ground upon which the barbarian nomads of the future will encamp in their mechanised caravans’. Here’s Virginia Woolf on shoppers in Oxford Street: ‘Here are hate, jealousy, hurry and indifference frothed into the wild semblance of life… I should stand in a queue and smell sweat, and scent as horrible as sweat.’ On and on it goes. They attack the rapid expansion of suburbia, and the social strata of white-collar workers – the clerks – who inhabit it, adrift in ’emptiness and meaninglessness’, as Mrs Leavis had it. They hold their noses at the thought of the tinned food being consumed by Ezra Pound’s ‘mass of dolts’, and at points, they dream of breeding, or, worse still, wiping the ‘dolts’ out.

The snobbery, the disdain for ‘the masses’, the transformation of their education and political empowerment into a threat to civilisation, is as shocking as it is unabashed. Yet, argued Carey, it underpinned the formation of what we now know of as modernism, driving it to its twin extremes of experimental formalism, in which form become the content, and those deep, streaming explorations of the inner world. Rebarbative, densely allusive, and radically rejecting the formal conventions of realist fiction, modernism, Carey argued, acted as a means to remove literature and the arts from those who, thanks to educational reforms, were gaining increased access to, and pleasure from, both. ‘The way the modernists reacted, it seems to me, was prohibitive – keep out these people, stop them from understanding… That is to say, to lock people out of art. Unless you’ve got some special reason for doing so, that seems self-defeating. Yet it seems to be quite clear that that was what Eliot, for example was doing.’ (‘Poets in our civilisation, as it exists at present, must be difficult’, decreed Eliot.)

But the lurch among intellectuals towards the inner, the abstract and the unfathomably complex did serve a function. It made appreciation of high modernist culture into a mark of social distinction, a way to separate, as lead Bloomsbury Groupie Clive Bell had it, the ‘educated personas of extraordinary sensibility’ from the ‘barbarian’ in his ‘suburban slum’. In other words modernist culture turned ‘being cultured’, possessing exquisite taste, having excellent aesthetic judgement, into a way of ‘scorning more than half of the human race’ who seemingly lacked those things. No wonder modernist writers and artists so often slipped, with barely a sliver of doubt, into supporting eugenics, and in Lawrence’s case, barely concealed dreams of mass extermination.

When it came out in the early 1990s, The Intellectuals and the Masses didn’t go down well among the contemporary arbiters of culture. As Carey recollects in The Unexpected Professor: ‘Reviewers seemed beside themselves with rage. It was alleged that I hated culture, and wished to condemn the population to “an endless diet of television soaps, the Sun newspaper, and royal scandals”. I was a commissar, an ally of Mrs Thatcher in her war against the arts, a lackey of the Murdoch press, and a puritan with a “class-based, priggish horror of champagne”.’ Such was the vituperative outpouring that the novelist Ian McEwan, ‘whom [Carey] knew a little’, wrote a sympathetic letter to him, saying, ‘this spiteful passion in the press suggests you must be doing something right’.

I ask him why he thinks The Intellectuals and the Masses prompted the negative reaction it did. Was it because he upset a literary and cultural establishment still too in thrall to modernism? Was its criticism too close to the anti-democratic bone of contemporary intellectuals?

‘I think the reaction had various explanations’, Carey tells me. ‘Your two suggestions are both relevant, I think. Also, people were indignant that ugly ideas could be pointed out lurking in hallowed texts. It seemed to them unfair and disrespectful. It was implied by more than one reviewer that as a professor of literature, earning my living from the great authors, I had no right to “foul my own nest”. Others said my quotations were taken out of context (though, of course, a quotation is, by definition, taken out of context). I think the reaction was one of shock, because, once one bothered to collect it, the evidence was so plentiful and so damaging.’

Yet despite the caricature of Carey that emerged in response to The Intellectuals and the Masses, as anti-intellectual and anti-modernist, the reality is very different. In fact, many of those writers whose ‘ugly ideas’ he showed to the world are also writers who have given him great pleasure – as writers. ‘One of the tangles you get yourself into when you try to tease out the different strains in that complex of modernism’, he tells me, ‘is that I find myself valuing enormously writers whose political views seem to me abhorrent, from Eliot’s anti-Semitism to Lawrence’s right-wing views. Some of the things Lawrence writes, such as rounding up “all the sick, the halt and the maimed” into a “lethal chamber as big as the Crystal Palace”, make your hair stand on end. But he’s a very great writer.’

What Carey is able to do, which his detractors weren’t, is to wrestle with that entangling of political belief and sublime literary expression, rather than suppress the former and elevate the latter. In fact, there might even be a necessary connection between their political beliefs and their literary expression. ‘So when you do your persuasion, I think it’s right to point out both sides. Read a bit of Lawrence’s travel writing, say; see how wonderful it is. At the same time, you need to know some of the things that Lawrence believed, which can seem pretty horrendous to us. So I think persuasion includes showing what to you are the best and the worst in a writer to whoever you’re teaching or talking to.’

‘To believe Lawrence’s writing is dangerous’, he notes in The Unexpected Professor, ‘is to assume that readers just suck it in uncritically, and it would be a strange reader who did that’. This is the democratic kernel at the heart of Carey’s critical enterprise: a belief not just in his own judgement, but in the judgement of others, too.

John Carey is a British literary critic. He is the author of many books, most recently, The Essential Paradise Lost, published by Faber & Faber. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK)).

Tim Black is editor of the spiked review.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.