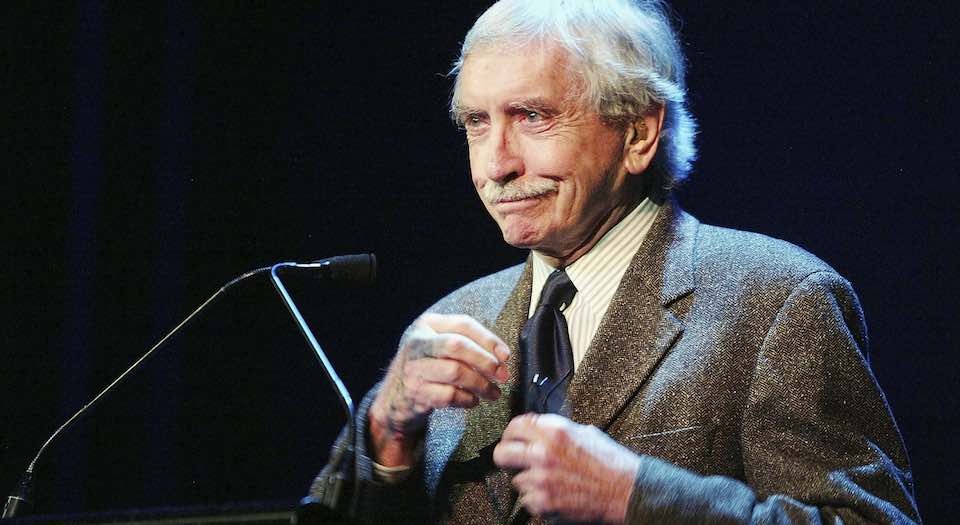

Who’s afraid of Edward Albee?

Two new London productions confirm Albee's greatness.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

A theatre director friend of mine once remarked that Edward Albee had written only one good play – Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962) – and had dined out on it ever since. This struck me at the time as curious. Could this be the same Edward Albee who had written over 30 plays in a career spanning five decades, including some of the most shrewd and excoriating theatrical depictions of 20th-century American domesticity? Was this the same Edward Albee who had been awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Drama on three occasions? For a one-hit wonder, that’s pretty good going.

In a way, my friend’s comments were unsurprising. Albee drifted in and out of fashion throughout his professional life. For much of the 1970s and 80s, he struggled to find producers who were willing to stage his shows in New York. As Albee himself pointed out, ‘To many minds, lack of New York exposure renders one invisible’. It wasn’t until he won his third Pulitzer Prize in 1994 that interest in his work was reinvigorated. ‘I have become visible again,’ he later wrote. ‘How long this will last I have no idea.’

He needn’t have troubled himself unduly. Albee was to retain his visibility on the theatre scene until his death last September, and there are at present two superb revivals running in London’s West End: Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? at the Harold Pinter Theatre, and The Goat or, Who is Sylvia? at the Theatre Royal Haymarket. Written 40 years apart, they showcase the consistency of Albee’s talent, and remind us that what is often perceived as an artist’s declining powers is more often than not merely a reflection of the capricious nature of literary trends.

Some of Albee’s best plays are those that, like The Goat, veer from poignancy to hilarity in the most unexpected ways. The Lady from Dubuque (1980) is one such play: snappy dialogue and whimsical moments of direct address are curiously offset by an ominous sense of impending tragedy. There are also his rarely staged Pulitzer-winners – A Delicate Balance (1966), Seascape (1975) and Three Tall Women (1991) – and his personal favourite, The Man Who Had Three Arms (1983), a play so reviled by critics that it almost ended his career.

His early work was hugely influential. As John Guare has observed, his debut The Zoo Story (1959) ‘spawned a whole generation of park-bench plays… To show you were avant-garde, you needed no more than a dark room and a park bench.’ Likewise, the scenario of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? – a night of vitriolic sparring between married couples, complete with drunken revelations of escalating severity – now feels overly familiar because it has been so often imitated.

Albee was all too aware of the pitfalls of success when it comes so early in one’s career. Reflecting on the critical mauling he received for Tiny Alice (1964), his follow-up to Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, he observed that commercially successful writers are at risk of being judged not by their artistic development, but ‘by how similar your new work is to the blockbuster’. But, as he put it, he was uninterested in ‘second-guessing the tastemakers’: ‘I go with what my mind tells me it wants to do, and I take my chances.’

The Goat is a case in point. The story of a renowned architect who is having an extramarital sexual affair with a goat was, on paper at least, unlikely ever to garner widespread critical acclaim. Some of Albee’s closest friends advised him not to proceed, fearing the play would do irrevocable damage to his reputation. This reaction strengthened his resolve to see it through. As ever, he was right to trust his instincts: The Goat was a critical and commercial triumph, winning the Tony Award for Best Play in 2002.

The plot isn’t shocking in of itself. Anyone with the slightest literary background will know that depictions of bestiality are commonplace in the classics. One need only read Ovid’s Metamorphoses to see that the occasional dalliance with livestock was once a common symptom of failing marriages. But in Albee’s play, the intrusion of such a socially impermissible form of desire into the stiflingly bourgeois family realm is deftly handled and undeniably entertaining. In these days of trigger warnings and hypersensitivity around the supposed moral responsibilities of the artist, Ian Rickson’s current production seems more relevant than ever.

Albee’s stated intention with The Goat was to test ‘the limits of tolerance’. This applies as much to his audiences as to the interpersonal relations of his characters, and is a consistent feature of his work. The overt sexual content of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? proved too much for many critics on its first outing in 1962; the New York Daily News likened the play to a ‘cesspool’. It was selected for the 1963 Pulitzer Prize, but the drama jury’s decision was overruled by the awards’ advisory board on the grounds that it was not sufficiently ‘wholesome’. The 1966 film adaptation was similarly contentious. Thanks to the insistence of first-time director Mike Nichols, the coarser elements of Albee’s dialogue were largely preserved, and the result was a landmark of permissiveness when it comes to profanity on the big screen.

The script has aged exceptionally well. James Macdonald’s production at the Harold Pinter Theatre boasts tremendous performances from all four cast members. In the hands of Imelda Staunton and Conleth Hill, Martha and George’s brutal games-playing is as powerful as ever. It is to be hoped that the success of the show, and that of The Goat at the Theatre Royal Haymarket, will lead to further Albee revivals. No doubt he will once again fall out of fashion, but with any luck that won’t be any time soon.

Andrew Doyle is a stand-up comedian and spiked columnist. Follow him on Twitter: @andrewdoyle_com

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.