Long-read

Beyond fake news

Renewing journalism’s pursuit of truth is absolutely necessary – for journalism and for society.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Aside from the ‘Trump bump’ in stock-market indices, perhaps the most surprising development of the Trump administration’s first 100 days has been President Trump’s ability to turn the term ‘fake news’ against the established media organisations who invented it.

Up until the start of this year, just one word – ‘fake’ – was enough to trigger anxieties about news stories allegedly being fabricated or endorsed by the Trump camp. The idea was that made-up stories were influencing legions of Trump voters living a life of ‘post-truth’ – governed by gut instincts, impervious to the facts. In December 2016 and January 2017, widespread talk of ‘fake news’ allowed the political elite, which includes the commentariat alongside politicians and policymakers, to evade responsibility for its multiple failings and point the finger of blame at the supposedly gullible masses. But by February 2017, the word ‘fake’ had already come back to haunt the media establishment. In their repeated references to ‘fake news media’, Trump and his officials were using the term against the very people who had put it out there in the first place.

Is this the result of President Trump’s unerring instincts? Hardly. The climbdown this month on his healthcare bill has already shown that his instincts are far from infallible. But Trump’s re-deployment of ‘fake news’ to target the media establishment resonated with millions of people. Preferring Trump’s personal Twitter feed to the Washington hack pack, many Trump supporters regard ‘mainstream media’ as fake. They already know that professionally produced news cannot be wholly true because for years now it has ignored them.

These people have lost patience with the journalists who failed to report their story, or record their concerns, just as they have lost patience with the snooty politicians who labelled Trump voters ‘deplorables’. Both politicos and journos have been equally disdainful of the masses; now they are bracketed together in the mind’s eye of much of the electorate.

In this context, journalism is not only set to be ignored; its studied ignorance of the people it professed to serve has put it in the dock alongside other sections of the self-serving elite.

In the UK, at the EU referendum, and again at the US elections, the electorates on both sides of the Atlantic returned a damning verdict on the elite. On the American side, the sentence was immediate – the continuity camp was sent into exile. Whereas in Britain it is beginning to look as if sentencing has been deferred, allowing a modified version of the political elite to manage yet another episode in the long drawn-out history of imperial decline.

Meanwhile, in a less dramatic way, the popular verdict on the media establishment has been delivered not at the ballot box, but in the gradual act, undertaken by millions of people, of un-friending professional journalism. Responding to journalism’s culpably poor performance in recent years, they have found that they can do without it – just as they can get by without the elite’s political wing.

In the UK and US, millions of voters are now as estranged from professional journalism as they are disconnected from political institutions. This double dose of alienation can only mean that de-journalisation is as much on the cards as de-politicisation – unless and until journalism takes decisive action to improve its understandably low ratings.

This is journalism’s last chance saloon. What journalists do now will not only decide the future of journalism; it will also determine whether journalism has a future as the oxygen of public life. Conversely, if journalists get it wrong this time, ‘public’ journalism will become little more than carbon dioxide emitted by the Westminster-Washington bubble.

Now is the time for journalism to prove itself. The present situation calls for journalism to rise to new heights and acquire greater breadth; it needs journalism which is both a forensic attaque and a rigorously humanistic account of significant events, composed in the spirit of generosity and understanding. If journalism is to emerge intact from its current crisis of relevance, it must renew its mission to pursue truth.

This is absolutely necessary – for journalism and for society. But it is also likely to prove difficult, not least because of widespread incredulity towards metanarratives, such as truth. Such ‘incredulity’ was once the exclusive preserve of trendy metropolitans and postmodernists, but it is now ubiquitous in Western society.

Journalism is not solely responsible for this incredulity, nor is it uniquely culpable for current levels of estrangement from the erstwhile public space where metanarratives were customarily forged. Yet some symptoms of the ‘postmodern condition’ have been self-inflicted – on journalism, by journalism. And only journalists can correct these.

During the first decade of the 21st century, professional journalism undermined its own reputation as the bearer of truth. Journalists declared the ‘death of the story’ and the onset of ‘news as a conversation’. The idea was that there’s always someone out there who knows more about the story than we do. In these seemingly self-deprecating assertions, journalists might be said to have written the longest suicide note in history. Thankfully, journalism didn’t go through with it, but serious damage was done.

These statements were merely the most explicit manifestation of journalism’s self-destructive descent from the level of public discourse – that is, talking together about what matters to us all – to a matter of personal perspective. The latter is no place for journalism to operate as the bearer of truth, since at this level there really is no universal truth, only truths (plural) relative to those persons proffering them (to whom they belong, each to their own).

Conversely, in order to renew its pursuit of truth, journalism must make the climb back up to that general level which is composed of particulars but also located beyond them; where truth is both universal and impersonal, since it is derived from and addressed to what we all have in common – our common humanity.

Having lived through a litany of failings on journalism’s part, many journalists are now keen to make amends. But journalism cannot hope to perform well in a new situation simply by rewinding to some of its earlier success stories.

Richard Sambrook, former director of the BBC’s World Service, has suggested that journalism must return to something like classical austerity: journalists should go back to the facts, and allow comment, slant or interpretation only when these are clearly flagged as such.

There is salience in such asceticism, not least because it deflates the self-indulgence typical of today’s intensely personalised journalism. But in the current context, there is also something inherently problematic in going back-to-basics.

There is worth in returning to the journalism of the inverted pyramid – that is, the classical format associated with a purely factual approach, in which the most important information comes first. This hierarchy is oriented towards a shared news agenda. In other words, when the logic of importance is also the organising principle of the story, what comes first is that which is most likely to matter to us all. Thus the mechanics of traditional news writing have also served as a mechanism capable of raising the story above the interpersonal plane, onwards and upwards to the level of public discourse.

For it to be fully effective, however, this needs to be grounded in the active presence of the public – the critical mass of people poised to interpret the factual and act upon it as it is put to them. In this sense, a news story only becomes ‘the news’ when it has been issued in order for it to be taken up and acted upon by the majority population. It is a mode of journalism that depends on the existence of mass political participation.

From the Spring of Nations in 1848 to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the epoch characterised by the development of social democracy, this news-reader relationship was at the heart of journalism.

But we cannot turn the clock back to the days of mass participation in the struggle for social democracy. Similarly, we cannot hope to renew journalism by going back to a set of expectations predicated upon this struggle. Accordingly, a return to the classical methods which originated in the era of social democracy, will not now have the galvanising effect which Sambrook and others are hoping for.

For straightforward factual reporting to regain resonance the mass of the population would have to will itself back into its former existence as the general public. Perhaps this will happen one day – but who knows when? Following the demise of social democracy, a dismembered body politic is not about to re-assemble itself on hearing ‘the news’. Conversely, ‘the news’ cannot now be what it once was, even if presented in the same form as before.

Rallying to first principles may be of some value, but it is by no means a sufficient response to the unprecedented demands of the present moment. Also, there is an additional sense in which the back-to-basics approach is not only insufficient; it could turn out to be worse than useless.

Even ‘timeless’ principles can only be implemented in a particular place at a particular time. There is some clamour for a focus on the facts, but only in the form of fact-checking the lies of so-called populists. It’s become a form of virtue-signalling, through which journalists, set against the ‘deplorables’, assert their moral worth.

Just as reports of fake news have been grossly inflated, so some mainstream media organisations are mounting an exaggerated response in the form of high-visibility fact-checking procedures. Of course, no journalist should ever send a news story over to the subs’ bench without checking it and re-checking it for factual accuracy. But in the current context, in the return to apparently straightforward first principles, there is more going on than meets the eye.

Fact-checking, the antidote to the fake news epidemic that never was, is fast becoming a badge of moral worth, and, conversely, a way of badging as unworthy those who do not sign up to ostentatiously transparent procedures. In response to the alleged onslaught of fake news, such transparency is said to be synonymous with the public interest. By the same token, it is spuriously assumed that news organisations that do not make a point of contracting into these pious procedures are in thrall to, or in the pay of, unsavoury interests.

Thus even the long-established fundamentals of journalism have been co-opted into yet another way of defining ‘the public interest’ without allowing readers, viewers and listeners to decide what that means. What appears to be a simple re-affirmation of first principles, is already aligned to a set of anti-popular prejudices. In the attempt to re-locate a genuinely popular journalism, therefore, the back-to-basics approach is set to be more hindrance than help.

On the other hand, a striking example of the breadth and depth to which journalism should aspire, is now showing at the Barbican’s Curve gallery in London. Incoming, by documentary photographer Richard Mosse, uses military imaging equipment to depict both migrants seeking entrance to Europe and the ‘incoming’ fire aimed at the regions they have migrated from.

It is the most striking rendition of current affairs that I have encountered since reading Tom Wolfe’s New Journalism anthology on the road to the Edinburgh Festival in 1975. In its stately, almost operatic style, this 52-minute film removes both migrants and military personnel from the constant churn of sub-standard journalism, and puts them on the plane of the universal. That is, the commanding heights that professional journalists previously thought of as both ‘the first draft of history’ and their second home. In so doing, Incoming calls into existence a public capable of locating itself on the level of our common humanity – the place where universal truth resides, and the place that journalism must now work out how to recreate.

The threat to journalism is also its moment of historic opportunity. Just when people proved willing to entertain fake news – if only for entertainment’s sake – at one and the same time the majority population also signalled its disdain for the fake democracy co-created by political and media elites. Not that the way in which voters expressed their contempt necessarily amounts to a new form of progressive politics – but by rejecting the elites, the anti-establishment vote signalled the possibility of moving beyond today’s pantomime politics.

We now have the chance to wipe off the make-up of a moribund social democracy and break into something new.

In this interzone between the demise of social democracy and the rise of a new round of politics, journalism has a significant contribution to make. Journalism could catalyse a new universality as the precursor to politics proper, as it managed to do in 18th-century London – something the exceptional Richard Mosse has only recently reiterated.

But for journalism in general to reverse the trend towards its own irrelevance, it will need to reboot the pursuit of truth through a programme of self-education and debate. We also need somewhere to reform journalism – to reformulate it by trying out new forms with the potential for reaching out beyond the failing grasp of established formats.

That’s why a new college of journalism is required, as the place where journalists young and old may gather together to learn from each other and work out how journalism can do better.

Andrew Calcutt is editor of Proof: Reading Journalism and Society. He is co-author, with Philip Hammond, of Journalism Studies: A Critical Introduction, published by Routledge. Buy this book from Amazon(UK).

In East London, a small group of journos has already laid out a future for journalism in their prospectus for a new college. If you can report, write, produce or edit on any platform but always with the future of journalism in mind, we would like to hear from you. You can contact me at [email protected].

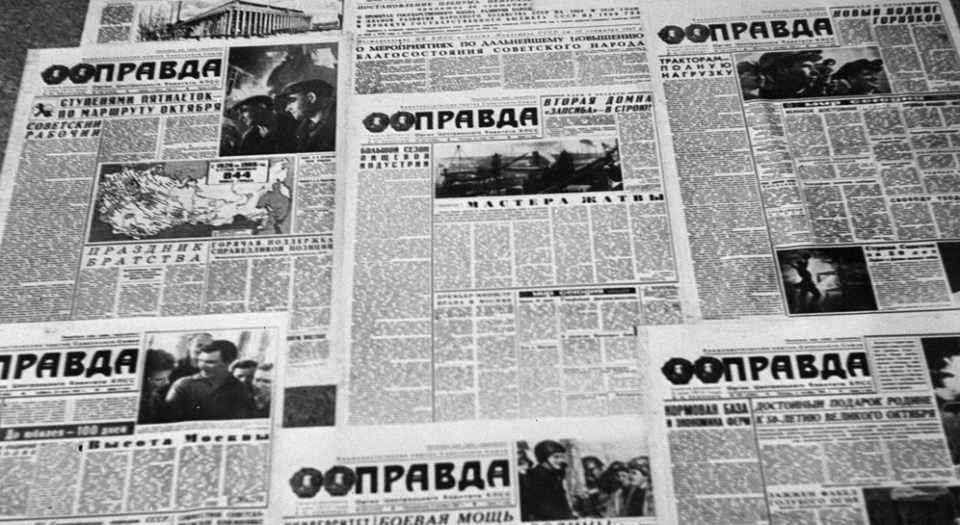

Picture courtest of RIA Novosti

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.