Experts and politics: why Gove knows better than Plato

In an extract from his new book, Mick Hume defends the public's right to choose.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Nobel Prize-winning geneticist Sir Paul Nurse reignited the row about the role of experts in public debate last week. Prompted by the BBC’s Brexit-bashing Newsnight programme, Nurse announced that former Tory minister Michael Gove’s referendum campaign remarks about how the British people ‘have had enough of experts’ were ‘irresponsible’ and meant ‘Those who are expert, who have the knowledge, who have the intellectual ability to dissect these difficult problems, are being derided and pushed back’.

In this edited extract from his new book Revolting!, Mick Hume argues that, while experts retain an important role in giving advice, it is dangerous to democracy to empower them to give instructions about the political choices we make.

What proved to be the most controversial statement during the EU referendum campaign? Not Boris Johnson’s overblown comparison of the EU with Hitler’s Germany. Nor prime minister David Cameron’s desperate claim that leaving the European Union could spark the Third World War.

No, the statement that caused most outrage in political and media circles was Leave campaigner and then Tory cabinet minister Michael Gove’s suggestion to a television interviewer that ‘I think the people of this country have had enough of experts’. The UK’s sizeable class of experts and officials, who were warning that disaster would follow a vote for Brexit, responded as if Gove had demanded that they all be lined up against a wall and shot.

The outrage was still boiling months later, when Lord O’Donnell – former head of the UK government’s civil service – was interviewed in The Times. ‘Perhaps most offensive to Lord O’Donnell’, noted the sympathetic interviewer, ‘was Leave’s reckless dismissal of expert advice’. O’Donnell the ex-mandarin seemed barely able to conceal his condescension as he pointed out that ‘when your car goes wrong, you actually do want to take it to a mechanic – an expert on cars. I wish Mr Gove very good luck when his car goes wrong and he decides he’s not going to have the experts involved.’

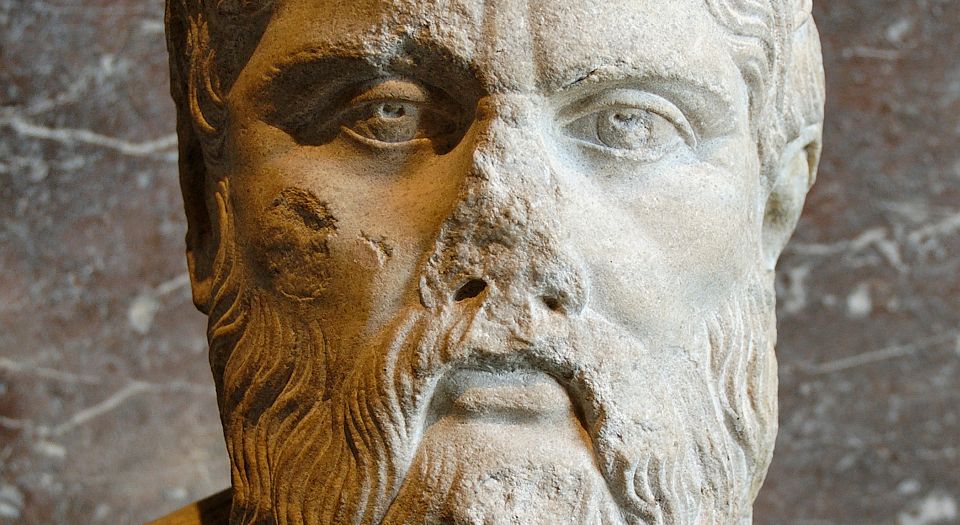

The argument that experts are better placed than ordinary people to make informed decisions about important issues facing society is an age-old case for undermining democracy that has come back into fashion lately. In Ancient Athens philosophers argued openly for replacing democracy with the rule of ‘the wise’ over the ignorant masses. They believed that, as one recent historian has it, democracy ‘gave people what they wanted from day to day, but it did nothing to make sure they wanted the right things’.

The philosopher Plato, through his written record of what his mentor Socrates was supposed to have said, offered an early and more explicit version of Lord O’Donnell’s argument about fixing cars. Plato’s Socrates had no inhibitions about spelling out his feelings against democracy. After all, he observed, when it came to deciding on technical matters such as shipbuilding (or perhaps, in another life, car maintenance), the popular assembly of Athens would consult the experts, not the ignorant. So why turn to people who lacked expertise in politics when deciding political issues?

It was ridiculous, Socrates asserted, that ‘when it is something to do with the government of the country that is to be debated, the man who gets up to advise them may be a builder or equally well a blacksmith or a shoemaker, a merchant or ship owner, rich or poor, of good family or none’. Nobody was willing to dismiss these lowly non-experts by pointing out ‘that here is a man who, without any technical qualifications, unable to point to anybody as his teacher, is yet trying to give advice. The reason must be that they do not think this is a subject that can be taught.’ Socrates by contrast believed that political judgements could and should be taught by experts, rather than left to the verdict of the vulgar and uneducated citizenry.

These days those who would put experts on a political pedestal are rather less honest about their opinions of the people. Of course we believe in democracy, they will insist, and of course the electorate must have its say. But… there are things about which ordinary people have little or no understanding. In these matters people should allow the experts to decide, or at least cast their votes according to advice/instructions given by those in the know.

For example, they might say, what does your average voter know about the setting of interest rates for the international money markets? And should the politicians who might do what their voters want, rather than what the capitalist economy really needs, be left to decide?

No, better by far we are told to entrust the setting of interest rates to the independent experts in the Bank of England, the European Central Bank and the US Federal Reserve. Never mind that millions of lives will be directly affected by whatever the bankers decide to do. Democracy is all very well in its place, but its place is apparently not at the financial top table.

The important thing about ‘independent’ central banks is that they are supposed to be independent of any political interference – otherwise known as, democratic control. The central banks were handed these powers by politicians trying to offload democratic accountability. In the UK, the ability to take ‘independent’ decisions on setting interest rates was granted to the Bank of England by chancellor Gordon Brown after Labour won the 1997 General Election. Elsewhere in Europe the idea that electorates and elected politicians cannot be trusted to know what the economy needs has been used by the EU and the IMF effectively to usurp the elected governments of Greece, Italy and Ireland and impose technocratic experts to run the country as the markets require.

There are many other areas we are told voters do not understand. Bring on the experts to guide the process of government. Give power to unelected and unaccountable bodies, the courts, commissions and consultants, the auditors and official inquiries, to make informed decisions and proposals that are beyond the ken of the voters in the street. And of course, line up the experts and officials to lecture the electorate about how they must vote in the biggest political referendum in memory, or an election for leader of the free world – and then castigate millions of the feckless little citizens for failing to do as they are ‘advised’.

Expert advisers have an important role to play in democracy. But there are questions which any amateur should ask before accepting that they know what’s best for the rest of us.

First, why should academics and experts be taken at their word, even on the issues about which they claim expertise? The word expert comes originally from the Latin verb meaning to test, try, find out, prove. They in turn should always be tried and tested to prove their expertise by experiment and experience.

The full version of what Gove said – while being constantly interrupted by the Sky News interviewer Faisal Islam – is worth digging out. ‘I think the people of this country have had enough of experts from organisations with acronyms saying that… they know what is best and getting it consistently wrong because these people… because these people are the same ones who have got it consistently wrong…’

And that was as far as he got. But the meaning was clear enough. Not a dismissal of expertise in general, but of the specific ‘experts from organisations with acronyms’ – the EU, the ECB, the IMF, the CBI – who were telling the British people they had to vote to Remain or face imminent economic catastrophe. As Gove observed, these were the same experts who ‘have got it consistently wrong’ about what was going to happen to the economy. Not one of them, for example, correctly predicted the financial crisis that struck the West in 2008.

So having tried and tested the economic experts on the basis of their experience, why should anybody have swallowed their instructions without question on how to vote in the EU referendum? Expertise in an area is not the same thing as infallibility. These people and institutions were often making political statements about their own support for the EU, disguised as expert economic advice.

Second, if experts are meant to be the unimpeachable source of public wisdom, what is the public supposed to do when different experts disagree? There are relatively few pressing issues where all scientists or authorities will concur with one another about the causes and consequences of a problem.

And what about the many occasions when the experts change their minds, and yesterday’s heretical fringe nonsense becomes today’s accepted wisdom, or vice versa? These flip-flops appear particularly common among the supposed experts on issues of public health. It often brings to mind the words of American author Mark Twain, who advised readers to be careful when reading health books as ‘you may die of a misprint’.

The problems of experts disagreeing and changing their opinions highlight the importance of people hearing all the evidence and making their own judgements about what they believe to be true. This is truest of all in politics.

This focus on the role of experts continually confuses technical expertise with political judgement. The good Lord O’Donnell is correct, of course, in advising Mr Gove to take his car to a mechanic. We generally go to a qualified expert for car repairs – or, in Socrates’ examples, for advice about shipbuilding or engineering projects. It does not follow, however, that a car mechanic or an engineer should go to a supposed expert in economics or political science for guidance on how to vote. Their expertise is far more questionable than that of technical experts; as even Daniel Kahneman, winner of the Nobel Prize for economics, concedes, ‘in long-term political strategic forecasting, it’s been shown that experts are just not better than a dice-throwing monkey’.

And regardless of how well read and accomplished these experts might be, this is politics. It is about values, morals and judgement far more than bare facts and figures. It is about everybody taking part in a democratic debate and coming to their own decision. Democracy is founded and survives on the assumption that every citizen is equally capable of making that choice for themselves. That is why the mechanic and the academic expert get one vote each.

Despite Socrates’ apparent disgust with the idea, political judgement really is not ‘a subject that can be taught’. It can certainly be learned – through debate, experience and interaction with others. But not taught, by expert instructors feeding you facts and The Truth, as if they were explaining an instruction manual. Democracy must involve trusting the judgement of the electorate, the wisdom of the masses, even if there are no guarantees they will produce the result you want.

If somebody counters that we need more ‘informed choices and decisions’, the question arises: informed by whom? In pursuit of whose interests? Who believes in expert or ‘fact-checking’ angels, floating on a cloud above the morass of humanity below, with no agenda to pursue or axe to grind?

We can certainly turn to experts for information and facts. But how that information is interpreted, what meaning we assign to those facts – this is the business of politics. And politics is above all about making a choice. So, for example, in a debate about Brexit and its impact on the economy, we could well accept that the UK might be in for a bumpy ride, at least in the short term, but still think that democracy and freedom from the EU was ultimately the most important consideration.

It is worth looking back to the French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville who, nearly 200 years ago in his classic work Democracy in America, argued that a democratic society needed a good system of public education to thrive. What it did not need, however, was anybody acting like ‘father figures’, laying down the law to the people as if they were teachers lecturing a classroom of children. That could weaken the popular resolve to take responsibility for their own circumstances just as surely as an authoritarian government. Tocqueville said of American voters then, ‘I do not fear that in their chiefs they will find tyrants, but rather schoolmasters’. That is a warning to ring down the years to our age of expert would-be schoolmasters.

Mick Hume is spiked’s editor-at-large. His new book, Revolting! How the Establishment is Undermining Democracy – and what they’re afraid of, is published by William Collins. Buy it here.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.