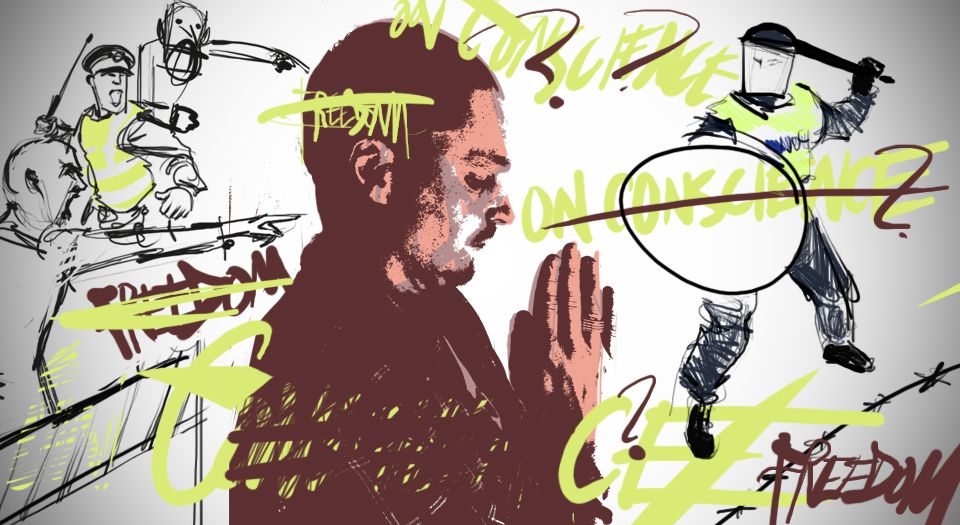

Christians: enemies of the state

Attacks on Christians’ freedom of conscience are attacks on us all.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Is it wrong to express what you believe is right? Is it wrong to want your life to accord with your moral convictions? Yes, it is, if you follow the logic of the rather disturbing case of the UK-based Christian couple who, in the past month, were denied the right to adopt the two children they had been fostering since early this year.

As reported in this weekend’s Sunday Times, the unnamed couple had been thinking of applying to adopt the then pre-school-age children, but had been put off by social services saying their house was too small. Then, earlier last month, they were told that a male gay couple was keen on adopting the children. According to the social worker’s case notes, ‘this suggestion is very challenging for [the husband and wife]’. This ‘suggestion’, it seems, also prompted an adoption application from the Christian couple, one that was rejected by social services, following the social worker’s report, on the grounds that their views on gay adoption were ‘concerning’, and ‘could be detrimental to the long-term needs of the children’.

So despite social workers having hitherto noted the couple’s ‘lovely care and warmth’ for the children, the couple’s belief that children are best cared for by a ‘mother and father’, grounded, as they put it in a letter to the local council, on their ‘Christian convictions’, ruled them out as prospective parents. It didn’t matter that they expressed their beliefs in ‘modest, temperate’ language. Nor did it matter that in subsequent exchanges with the local council they rejected the accusation of homophobia, declaring ‘we love everyone (regardless of sexual orientation)’. Their ‘views’, their ‘opinions’, their deeply held beliefs, were deemed the wrong views, the wrong opinions, the wrong beliefs. They were not free to act according to their conscience because their conscience was deemed regressive, discriminatory, offensive.

Perhaps such a case could be ignored as a local aberration, a staffing quirk of that particular state agency, a result of a specific social worker’s self-righteous zeal. Except that this case is far from unique. This year alone, we have seen Richard Page, a Christian magistrate, suspended as non-executive director of an NHS Trust because of doubts he raised about same-sex adoption on a BBC news programme. We’ve also seen Felix Ngole, a 38-year-old Christian postgraduate student, expelled from his social-work course at the University of Sheffield for voicing opposition to gay marriage in a Facebook discussion. And these cases themselves follow on from the well-publicised, drawn-out legal disputes involving Christians and equality laws, from the B&B owners who refused to let a gay couple stay to the bakery that refused to ice a cake with a pro-gay-marriage slogan. The faithful felt the demands violated their sense of what was right; the offended, seeking legal redress, felt the faithful were violating their esteem.

This is not to suggest that the rights and wrongs of people’s beliefs are not up for debate – they are. When, in the late 17th century, John Locke famously defended the freedom of Protestant sects to practise and associate according to their beliefs, he certainly didn’t defend the content of those beliefs – that was always a matter of rational contestation, rather than forceful coercion, as he saw it. Likewise, to defend the freedom of those Christians today who refuse to endorse same-sex marriage, or who believe that a heterosexual couple provides the best environment to raise a child, does not entail defending the beliefs themselves; rather, it entails defending people’s right to hold and practise those beliefs where, as Tom Paine had it, ‘their practice doesn’t disturb public order as established by the law’. What is important here for anyone who cares about our freedoms are less the contents of the beliefs than the significance of their state-driven, legally codified restriction.

Make no mistake: what we are in midst of here is a historic shift, a shrinking of the hard-won sphere of liberty, a rolling back, in this case, of everyone’s freedom of conscience. This is not to be downplayed just because it involves ‘gay cakes’ and putative bigotry in a B&B. The idea of one’s conscience is fundamental to a sense of one’s ethical freedom, denoting, as it does, that relationship one has to one’s inner, moral voice. The idea of conscience has developed and deepened over millennia, from Socrates’ Daimon, via the God of Saints Paul and Augustine, to Kant’s moral reason. And that conceptual expansion has gone hand-in-hand with a political struggle for ever greater freedom to pursue one’s own vision of the morally good life, from the Reformation to the American Bill of Rights and its insistence that ‘Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…’. And with each stage of this struggle, we have carved out a spiritual, inner, moral space – call it what you will – free from the dictates and commands of those in power.

Until now. Because with the passing of the Equality Act during the last days of New Labour, and the predominance of the ethos of anti-discrimination, this inner space is no longer impervious; it is now all too permeable, a transparent site of external monitoring, regulation and intervention. A Christian baker is no longer free to refuse to endorse a message that violates his conscience. And a Christian couple is no longer free to express, and act upon, their belief that a man and a woman provide the ideal home for a child.

It is because of the threats posed to freedom of conscience – not just for the religious, but also for everyone who values their moral autonomy – that we at spiked are staging a half-day conference on 16 November on the state of religious freedom today. It’s a unique opportunity to explore the clash between freedom and equality laws, the history and significance of the role of conscience, and the question of whether we should be free to hate. And we have an excellent line-up of speakers to help us get to the heart of the issues, including: human-rights activist Peter Tatchell, Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg, legal commentator Joshua Rozenberg, philosopher Roger Trigg, our very own Brendan O’Neill, and many more. For more information, speaker details and to buy tickets, visit the conference hub here.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.