You’re so vain you think this refugee crisis is about you

Both sides in the child-refugee debate are astonishingly self-obsessed.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Who’s worse: pro-refugee observers who want to mother the children of Calais, or anti-refugee scaremongers who want to keep them out of Britain? The infantilisers or the criminalisers? Those who view refugees as overgrown infants in need of the tears and care of loving Westerners, or those who see them as potential destabilisers of Britain, strange adults only masquerading as kids so they can come here to do bad? It’s hard to tell. They might be as bad as each other. One thing is clear, though: for all their wordy clashes in the press and on Twitter, both sides in the great child refugee non-debate share something important in common: they see these migrants less as individuals with autonomy and aspirations than as symbols of something or other through which we might make a point about ourselves.

The speed with which the question of what should be done about the younger refugees of Calais became All About Us has been alarming, even by the standard of today’s showy, signalling public culture. All sides are treating the migrants as props for political point-scoring. On the ostensibly pro-refugee side, whose heroes are tearful Lily Allen and football commentator turned brave tweeter for migrants’ rights Gary Lineker, the migrants are being marshalled to rescue a sense of British compassion, of moral mission, and of course to do down Brexit. The sour discussion about the refugees is apparently ‘a good indication’ of what ‘post-Brexit Britain is going to look like’. Indicator, symbol, message — we’re hearing these words a lot, because these refugees are largely walk-on actors in Britain’s own moral psychodramas, not individuals in themselves. Meanwhile, on the anti-refugee side, the young men of Calais are treated as symbolic of the corrosion of borders and the spread of the Islamist menace. Apparently, keeping them out of Britain would have shown we’re tough on such things. It’s symbolic compassion vs symbolic security.

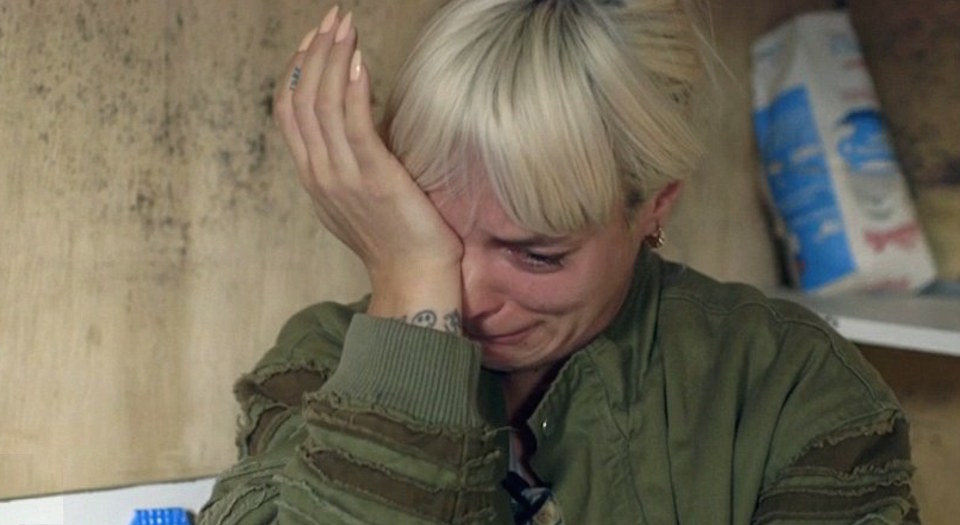

Narcissism runs through the discussion. The question these refugees raise is ‘What kind of people do we want to be?’, says one columnist. The keyword here: ‘we’. On the supposedly pro-refugee side, the game of self-reflection has been intense. Witness Allen’s TV-camera tears when she was chatting to an Afghan boy in Calais, after which the entire discussion became about her. Her image was everywhere. There was a thinkpiece war, some saying ‘Allen was right’, others saying ‘Allen was wrong’. It became about the role of celebrities in public life and whether emotionalism has a part to play in political decision-making, with the migrants reduced to mere objects of our self-reflection, and our tears, not the subjects of their own story.

Then there was Stella Creasy, the self-promoting Labour MP, interviewed in the London Evening Standard, promising to stand up for these child migrants regardless of how much flak she will get (shorter version: ‘I am brave’). The piece was accompanied by a massive picture of Creasy: no image of refugees, just her, because this is about her, not them. Then the story became all about Lineker, after he tweeted his concern for the refugees and was blasted by the Sun for doing so. What is the role of BBC people if not to be morally switched-on, a thousand op-ed scribblers asked, because this is about the Beeb, and the media, and us, not them. Jeremy Corbyn got stuck into the discussion of ‘what kind of people we want to be’ by praising Allen and Lineker for showing ‘Britain at its best’. It was a surreal illustration of the evacuation of substance and seriousness from public debate and their replacement by The Spectacle, largely of emotion: a political leader hailing media representations of sorrow for migrants over anything solid or concrete in relation to the actual lives of the actual migrants.

The media discussion has provided a striking insight into what being pro-migration largely means today: that you – the keyword being ‘you’ – are compassionate. Migrants are latched on to, not because of a genuine commitment to the idea of free movement (witness Creasy saying of course some migrants will have to be kept out), but rather as a means of self-distinction. To be pro-migrant is to be superior to those badly informed Others, who have a name now: Brexiteers. This is why so much of the child-refugee discussion has become bound up with Brexit-bashing. ‘What do we see each morning, post-Brexit, when we look in the mirror?’, asked a Guardian columnist of the child-refugee situation (keyword: ‘mirror’). He says we see a nation ‘hollowed out in terms of compassion’, but of course he means that is what ordinary, ugly, Brexit-voting Brits see in the mirror, not the migrant-loving Brits at the Guardian.

Another observer says the anger over the refugees shows ‘our society is not as enlightened as some of us had hoped’, meaning ‘not as enlightened as me’. The child refugees are reduced to a mirror into which right-thinking Westerners can look and see their own decency reflected back to them, in contrast with the hatred among the Others, that is always ‘bubbling away beneath the surface’. Their vanity is astonishing. They’re so vain they think someone else’s continent-crossing hardship is about them.

The transformation of migrants into tools of self-distinction for the enlightened explains why observers are so keen for the migrants to be defined as children. To some of us, like spiked, it doesn’t matter if they’re kids, teens or adults: the length of their journey and the strength of their desire to live and work on Britain are surely sufficient to grant them access. But it matters a great deal to the pro-migrant self-differentiators because through infantilising these refugees they can assume an even greater adult, ‘enlightened’ sense of authority in the discussion of their predicament and of the unenlightened’s attitudes. The weaker and more childlike the migrants appear, the more of a moral thrill their self-styled saviours in the British media get from acting with a kind of moral in loco parentis. Their desperation to infantilise these clearly teenage, capable travellers is not merely about ensuring they get into Britain under treaty agreements relating to refugees under 18 – it is also about providing themselves with that satisfying feeling of responsible adulthood that comes both from caring for these foreign victims and chastising the hateful, childlike natives who have not given a good answer to the burning question, ‘What kind of people do we want to be?’.

The narcissism of the other side is striking, too. It is hard to believe that these right-leaning observers really believe that 70 young people coming to Britain will have any kind of terrible impact. And yet they demand that the arrivals’ teeth be checked to see how old they are, and furiously tweet photos of the young men with adolescent moustaches and mobile phones as if to say: ‘See! They’re grown-up! They’re dangerous!’ This is a performance of toughness, of security, to match the performance of compassion of the other side. Just as the pro-refugee side sidelines serious debate about freedom of movement and the role of their beloved EU and its Fortress Europe in creating this crisis, so the anti-refugee side dodges difficult questions of what is really causing a sense of insecurity in 21st-century Europe in favour of turning a handful of young refugees into symbols of existential disarray. Indicators, symbols, mirrors – that’s all these people are, to both sides.

The end result is that the migrants are dehumanised, by both parties. The pro-refugee side diminishes the young people’s moral autonomy, and their resilience in the face of war, hard journeys and life in that ‘Jungle’ (strikingly it was Lily Allen who cried, not the young man who had been through hell). And the anti-refugee side reduces them to gurning threats, harbingers of instability. There’s so little humanism in the discussion, so little true solidarity with these individuals. Let them come in, as people with will and freedom, not puppies to be looked after or criminals to be condemned.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.