Samsung: recalling the future

The response to the ‘exploding phones’ fiasco reveals a fear of innovation.

Over the past few weeks, Samsung’s ‘exploding’ Galaxy Note 7 has caught headlines, with reports that there had been a ‘spate of explosions’ due to faulty batteries. In fact, this amounted to just 35 red-hot or fiery phones among an initial batch of 2.5million – an incidence of danger that, while regrettable, is still vanishingly small. But that was hardly mentioned.

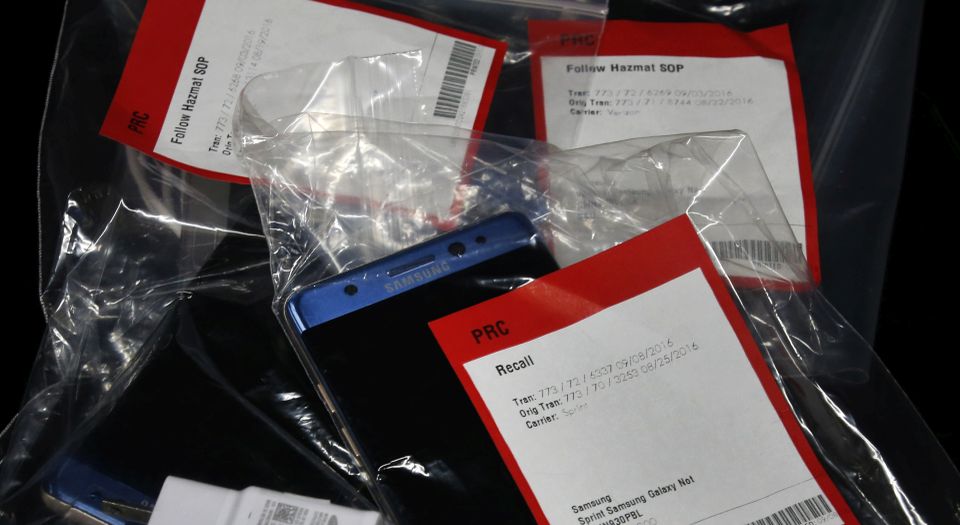

Samsung made headlines again when a handful of replacement models in the US also became red-hot pokers. Samsung has since instituted a blanket halt to sales, and has permanently closed down the manufacture of the Note 7. A BBC newscaster suggested that Samsung had ‘gone up in smoke’.

What the sensationalist press reports missed is that many products experience teething problems. While one or two people ended up in hospital as a result of the defective phones, no one was seriously hurt or killed. Samsung’s critics, it seems, would rather throw mud than put these accidents in context. And sadly, this may have a chilling effect on future innovation.

The Note 7 works underwater and checks its user’s identity by scanning the user’s iris. Unless radical new products like this are allowed to fail a bit, there will be no progress. In the US, there were barely any problems reported by Note 7 users. And yet, as soon as word got out about the defects, telecoms companies like AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile and Verizon were quick to offer users other deals and handsets.

Samsung will not go up in smoke because of the Note 7. It is a company with a turnover of €177 billion (£159 billion). In 2014, its R&D budget stood at more than €12 billion (£10 billion), which was worth a creditable 7.9 per cent of sales and was topped, worldwide, only by Volkswagen. These massive figures cover just the electronics section of the Korean conglomerate, which also handles construction, trading, chemicals, electromechanical gear and more besides.

Samsung will have no problem covering the costs of recalling and replacing the Note 7. Its mainstay phones, which are cheap compared with the niche Note 7, will be unaffected. What with the massive job cuts the company is putting through this year, Samsung anticipates a reasonable growth of profits for the third quarter of 2016.

Mass markets, though they have their faults, must be allowed to test the merits of new products in practice, beyond checks in the laboratory. Like Tesla cars, hoverboards and electronic cigarettes – all of which have been known to catch fire – the problem with the Note 7 is not really the product itself, so much as issues surrounding its battery. Batteries vary, but the combined advances in battery size, heat, cost and speed of charging has thrown up a number of issues. Since 1976, even simple 10 per cent improvements in the efficiency of high-tech batteries (as measured in labs, not real life) have mostly taken more than a decade to achieve.

The Note 7 debacle shows that modern capitalism is plagued by hamfisted product development and slothful technological innovation. Indeed, manufacturers are making more and more defective products. In the US, Samsung washing machines have had problems, and car manufacturers collectively recalled a record 51.2million vehicles in 2015.

Many recalls simply stem from a fear of litigation. In recent years, an army of lawyers and insurers has played on this fear, and there are countless regulations to comply with across the globe. No wonder manufacturers and exporters worry about innovative new products – most of them are only now learning how to add services, such as product recall, to their hardware offers. They don’t want to be left picking up the pieces of products that, perilous or not, may be made subject to regulatory sanction and social stigma.

The schadenfreude enjoyed by the media over Samsung’s setback isn’t just a case of ‘scary news sells’. It flows from a deep-seated cultural pessimism about what is possible and desirable in innovation. Stock markets marked Samsung’s shares down by excessive amounts, prompting commentators to claim that ‘reputational’ damage would afflict all of Samsung’s products and sectors.

As for Samsung’s mobile phones, one technology website concluded: ‘The Note 7 was a flagship device with flagship performance and a flagship price tag – if Samsung couldn’t nail down the quality on one of its most important phones of the year, how does it expect us to trust it enough to build safe new ones?’

Yes, let’s give up on Samsung. Too much could go wrong. In short: innovation is too risky, let’s recall the future.

James Woudhuysen is editor of Big Potatoes: the London Manifesto for Innovation. Read his blog here.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.