What would Sixties rebels make of consent classes?

The student movement was born out of the demand for sexual liberation.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

If you want an example of how thoroughly today’s campus activists have lost the plot, look no further than mandatory consent classes. After starting life in the US, these workshops – now rolled out at more than 20 UK campuses – are at the cutting edge of campus Orwellianism. (As Brendan O’Neill has pointed out, there is a profound irony in making classes on consent mandatory.) But, more crucially, this creepy desire to regulate students’ sex lives – pushed, in the main, by student leaders themselves – is undermining the hard-won gains of student activism itself.

As this new academic year has begun, there have been pockets of resistance to consent classes. At the University of York, students staged a walkout. ‘Consent talks are patronising’, 23-year-old student Ben Froughi told the Mail. ‘If students really need lessons in how to say yes or no then they should not be at university.’ Last week, at Clare College, Cambridge, a consent class was held, and no one showed up. Clare’s women’s officer posted a picture of the empty lecture hall on social media, decrying students’ evident apathy as a ‘huge step backwards’. She later deleted the post.

Consent classes are presented as a necessary response to a burgeoning problem. The NUS claims that one in seven women experience one form of sexual harassment or assault during their studies. This has been roundly discredited, due to its conflation of everything from unwanted advances to physical assault. But, in response, campus leaders have only cooked up even more outlandish claims. A survey conducted by Cambridge’s Women’s Campaign claims that 77 per cent of female students experience sexual harassment, which, it turns out, is defined as including ‘making comments with a sexual overtone’.

These bizarre workshops – which advise students to secure ‘enthusiastic, verbal consent’ for each stage of congress – may seem little more than a mood killer, but their impact is deadly serious. Students are safer on campus than just about anywhere else; these workshops will only make students wary of embracing their newfound freedom. Worse still, they undermine students’ autonomy – the idea that they, as adults, are capable of negotiating their intellectual, political and social lives for themselves. And it is precisely these kinds of prudish, authoritarian practices that students once railed against.

The idea that female students must be protected from their libidinous male counterparts is nothing new. Indeed, it underpinned the in loco parentis responsibilities universities once held over students. Until the late 1960s, dorms were gender segregated and curfews were enforced by live-in minders. And as Pat Cryer, a student at Exeter in 1957, notes, the burden fell largely on young women. ‘The lights in the porch would flash two minutes before [curfew] as a warning. Then the couples dotted around the porch would separate… Clearly the male undergraduates didn’t have such stringent requirements, as they would have got back considerably later.’

Things were just as bad in the US. In the late Fifties, Cornell University banned male-female socialising at off-campus parties – a dastardly loophole in the in loco parentis system. ‘Since the apartment situation is conducive to petting and intercourse it is an area with which the university should be properly concerned’, a spokesperson said at the time. At Oberlin College, male students were only allowed to visit women’s dorms for two hours on Sundays, and couples had to have at least three feet on the floor at all times. They also had to attend ‘mandatory sex-education lessons’. Why does that ring a bell?

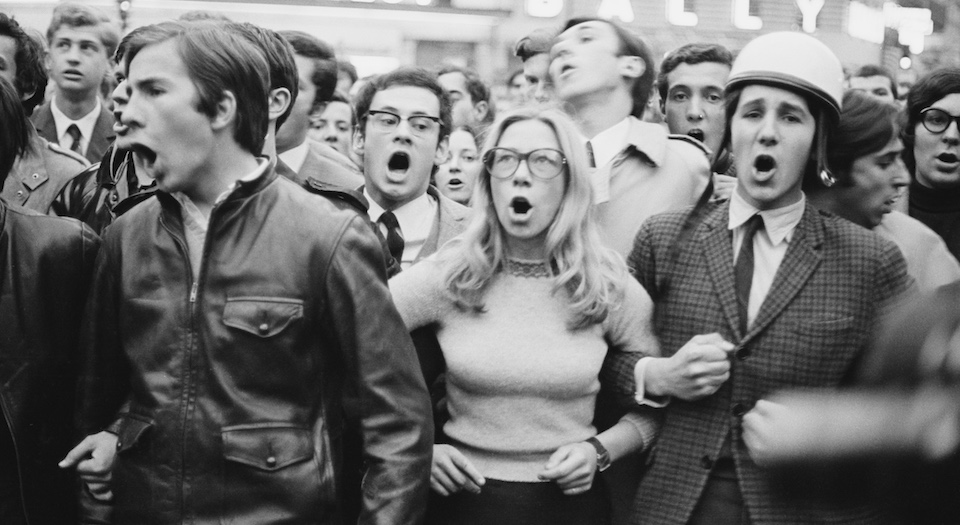

Unlike the fearmongering student activists of today, the students of the Fifties and Sixties demanded that campus officials butt out of the bedroom. At Cornell in 1958, students staged a series of protests and curfew walkouts, culminating in hundreds of students burning an effigy of the university president outside his home. He was forced to step down. In 1960, Oberlin students distributed a handbill, lambasting the ‘prudes and perverts’ of the administration: ‘We hereby declare ourselves independent of those fools who think that love and loving can be legislated. We will fuck when we want to fuck.’

The modern student movement was born out of students’ desire to be treated as adults. When the Free Speech Movement began at the University of Berkeley in 1964, the demand to lift the Red-scare restrictions on political activism was bound up with the demand to lift in loco parentis itself – to have total autonomy over their social as well as intellectual lives. That then California governor Ronald Reagan would later lambast revolting Berkeley students as ‘communist sympathisers, protesters and sex deviants’ was no accident. Political dissidence and sexual depravity were seen as intimately related.

The students of the Sixties realised this. It is only in insisting on being treated as an adult – free to think and to fumble – that you become an autonomous being, an agent in the world. That’s why the battle for sexual liberation then – the demands for abortion, contraception and an end to neo-Victorian values – went hand in hand with radical political agitation more broadly. And that’s why student activists today – languishing in the Safe Space, swatting up for their consent class – seem so prudish, so un-radical, by comparison. A step backwards indeed.

Tom Slater is deputy editor at spiked and the editor of Unsafe Space: the Crisis of Free Speech on Campus. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Slater_

Picture by: Getty

Sources:

‘The Challenge to In Loco Parentis, Campus Masculinity, and Administrative Anxiety (1960-1970)’, Oberlin College LGBT Community History Project

‘Campus Confrontation, 1958’, by Glenn Altschuler & Isaac Kramnick, Cornell Alumni Magazine.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.