The tragedy of Nahed Hattar: how censorship breeds violence

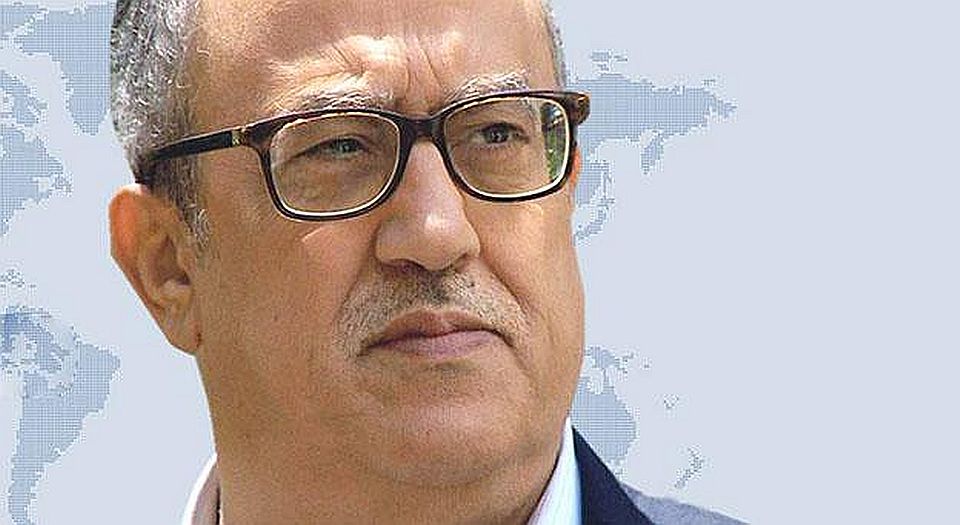

The killing of Nahed Hattar speaks to the new intolerance.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Yesterday, Nahed Hattar, a writer and political activist, was shot dead in broad daylight outside a courthouse in Amman, Jordan, where he was due to stand trial for the crime of posting a cartoon on social media that was considered offensive to Muslims.

Hattar was arrested in August. The cartoon depicted a jihadist, in bed with two women, who orders God, also pictured, to bring him a glass of wine. Any depiction of Allah is considered an offence to Islam in Jordan, and so Hattar was charged with violating religious laws and causing ‘sectarian strife and racism’.

This was the first death of its kind in Jordan, a Muslim-majority Middle Eastern country that is usually known for its relative stability, and its peaceful coexistence of Muslims and Christians. Compared with most other Muslim countries, Jordan is considered moderate. But in a state where someone can be punished for criticising religion, what does ‘moderate’ really mean?

Hattar was Christian-born, but described himself as a ‘non-believer’. He was an anti-Islamist activist and known for being a controversial writer, but he didn’t go out of his way to offend. When he came under fire for posting the cartoon, which was titled ‘God of Daesh’, he apologised and said his intent was to mock ‘terrorists and how they imagine God and heaven… [the cartoon] does not insult God in any way’.

Similar to what happened in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo killings, Hattar’s death has been met with mixed responses. The Muslim Brotherhood, the ultra-conservative Muslim political party, condemned the shooting collectively, but Brotherhood MP Dima Tahboub also wrote on Twitter: ‘Seculars are the downfall of our society.’ And while some have taken to social media to stand up for freedom of speech, others have openly celebrated Hattar’s death.

A Jordanian government spokesman said: ‘The law will be strictly enforced on the culprit who did this criminal act and will hit with an iron fist anyone who tries to harm [the] state of law.’ The Jordanian government is right to speak out strongly against this despicable murder, yet while we must not diminish the responsibility of the gunman – the suspect was named by security sources as Riad Abdullah – the state also shares part of the blame. Local news reports suggest that Abdullah was insulted by the cartoon, and therefore decided Hattar should be punished. He was taking the state’s censorious thinking, its decision to try and potentially punish Hattar, to a bloody extreme.

Legal restrictions on speech have an insidious effect. Not only do they foster a more censorious climate, they also give a green light to those looking brutally to silence views they dislike. As spiked argued in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attack, the fact that the French-born killers grew up in a society that censored hate speech is significant. Though this doesn’t justify their actions, nor strip them of their free will, it seems clear that a society that sanctions censorship will produce intolerant people.

Censorship is on the rise in Britain, too. Alongside our existing hate-speech laws, the authorities are beginning to clamp down on trolling, cyber sexism and, as was recently piloted in Nottinghamshire, ‘misogynistic hate crimes’. Just last week a British man – Paul Gascoigne – was taken to court for making a racist joke. The logic here is identical to that which underpins Jordan’s blasphemy laws, or the motive of Hattar’s killer: people must be punished for stepping outside the parameters of acceptable speech.

You may think this is an exaggeration, and that our society is worlds apart from Jordan’s. But ask yourself this: every major media outlet in the UK reported on this story, but how many published the cartoon?

Naomi Firsht is staff writer at spiked and co-author of The Parisians’ Guide to Cafés, Bars and Restaurants.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.