The madness of Vincent Van Gogh

A new exhibition explores the Dutch master’s psychological torment.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

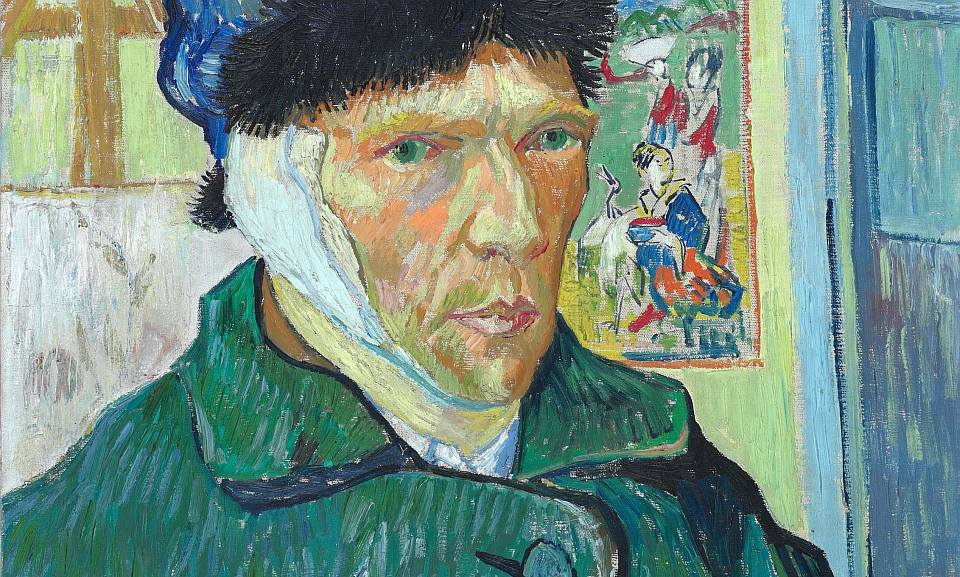

Until now, the way of testing whether or not someone had good biographical knowledge of Vincent Van Gogh was to ask them about the famous ear-cutting incident. The answer ‘he cut off his ear’ informed you the speaker had only a hazy comprehension, whereas the knowledgeable person replied ‘in actuality, Van Gogh cut off only part of his ear’. Now new information suggests that Van Gogh did indeed cut off his whole left ear. On the Verge of Insanity: Van Gogh and His Illness, a new exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (closes 25 September), accompanied by an excellent catalogue, attempts to get as close as possible to the truth about Van Gogh’s physical and mental illnesses.

The confusion about the ear incident sprang up during Van Gogh’s lifetime. On the 23 December 1888, Van Gogh was living with Paul Gauguin at the Yellow House in Arles. Gauguin announced his intention to leave Arles after persistent rows with Van Gogh. Deeply anxious and depressed, Van Gogh slashed his ear with a razor. He presented the ear wrapped in newspaper to a prostitute at a local brothel. The next day police discovered Van Gogh unconscious in his house surrounded by blood. Vincent’s brother Theo (who supported him morally and financially) raced from Paris on Christmas Day to comfort Van Gogh in Arles hospital.

Jo Van Gogh-Bonger (Van Gogh’s sister-in-law and someone who met him several times after the incident) claimed it was part of the ear, whereas doctors, policemen and reporters in Arles claimed it was the entire ear. Van Gogh became ashamed of his mutilation and attempted to conceal it, leading to the contradictory statements of associates. Some witnesses may not have seen the injury clearly and others repeated what they had been told. What seems to be the clinching proof that he did cut off almost his whole ear (except a stump of the lobe) is a diagram made by Dr Felix Rey, the attending physician in Arles.

While biographically interesting, the ear incident in no way helps us understand Van Gogh’s art. What does have more bearing on his artistic production and life is the multiple illnesses he suffered from. Irritable and melancholy by nature and prone to fixations on individuals and ideas, Van Gogh’s devotion to work led him to neglect his health. Though he spent on art materials, he ate poorly. The loss of most of his teeth in his early thirties led to gastric trouble. He suffered from insomnia. And he contracted gonorrhoea, and possibly syphilis.

Van Gogh’s poor diet, tiredness and overconsumption of alcohol and caffeine – plus his tendency to overwork – contributed to attacks of mania, which physicians at the time diagnosed as epileptic fugues. In these states, Van Gogh ate paint and attempted to drink turpentine and paraffin. He had seemingly no control over his actions and experienced visual and auditory hallucinations. After these attacks he would be overcome by lassitude, depression, his speech would be jumbled and he would fail to recognise familiar people. Even when not in these post-manic phases, he suffered from extreme nervous tension and paranoia.

There have been numerous suggested diagnoses of Van Gogh’s mental illness, but none is without flaw. Psychosis, bi-polar disorder, borderline-personality disorder, neurosyphilis, Meniere’s disease, poisoning and other suggestions have been put forward. Van Gogh never painted during his nervous attacks, but his illness and his (voluntary) confinement did influence his choice of artistic subjects and even his materials. During phases when he was considered at risk of relapse, he had no access to oil paint and was only allowed ink and watercolour. His attachment to religious subjects and the themes of family life and the life of prisoners were direct comments on his situation.

In Arles hospital, Van Gogh was treated for his wound, but it was clear he was mentally ill. The local postman, a Protestant pastor and a cleaning lady all made strenuous efforts to support Van Gogh, regularly sending Theo updates after he returned to Paris, leaving his brother in Arles. Van Gogh’s condition fluctuated. Local residents in Arles started a petition and gave a verbal deposition to the effect that Van Gogh’s lewd and unpredictable behaviour frightened people, that he had inappropriately touched women and followed them into their residences. A document was drafted which would have committed him to an asylum. Van Gogh – fully aware that he was ill and a danger to himself – voluntarily committed himself to an asylum in nearby St Remy.

In May 1889, Van Gogh moved from St Remy to Auvers-sur-Oise, a small village near Paris, where he could be close to Theo, Theo’s wife Jo and their baby. Dr Gachet, a friend of painters, would take care of Van Gogh. Though isolated and nervous, he was productive over the summer and seemed to have achieved equilibrium. On 27 July 1890, Van Gogh apparently shot himself while out painting in a field. He staggered back to his boarding house. Doctors determined that the bullet wound to the abdomen was fatal and inoperable. He died in his brother’s arms on 29 July.

Included in the catalogue is a photograph of a pistol recovered in 1960 from a field near the site of Van Gogh’s shooting. It is a reasonable assumption this artefact is the fatal weapon. The catalogue’s authors do not discuss the idea put forward by biographers Gregory White Smith and Steven Naifeh that Van Gogh was shot by local teenage boy Rene Secretan, a theory that prominent Van Gogh experts consider improbable.

The curators and writers have commendably resisted translating Van Gogh’s illness into explanations for his art, but they do show how his conditions influenced his life and outlook. It is unlikely that new material will come to light that will permit clear diagnosis of his mental condition, but this exhibition and catalogue do bring us closer to understanding the distress of one of art’s greatest geniuses.

Alexander Adams is a writer and art critic. He writes for Apollo, the Art Newspaper and the Jackdaw. His book On Dead Mountain is published by Golconda Fine Art Books. (Order this book from the Pig Ear Press bookshop.)

On the Verge of Insanity: Van Gogh and His Illness is at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, until 25 September. The exhibition catalogue, published by Mercatorfonds, is available to buy here.

Picture by: Courtauld Institute of Art.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.